A panel of 12 jurors and two alternates was seated this afternoon at the end of the first day of trial for Monserrate Teron, the 59-year-old man accused of sexually assaulting his 7-year-old niece in Palm Coast in November 2019.

Judged by the victim’s young age, it is the gravest case of abuse in Flagler County since Paul Dykes and Erin Vickers were both sentenced to life in prison in 2017 over the rapes of Vickers’s then-1-year-old daughter.

In the Teron case, the alleged victim and her sister were visiting Teron and his wife in Palm Coast from out of state and were spending a night at Teron’s home, as he was a trusted member of the family. He is accused of forcing her to perform oral sex on him.

There are allegations of abuse in Orlando, when the family was on a Disney trip, and in Massachusetts. Those will not be introduced at trial since they are out of the Flagler jurisdiction. The counts focus only on allegations the Flagler County Sheriff’s Office and the State Attorney’s Office investigated in Palm Coast after getting tipped off from police in Massachusetts. But trial testimony will include that of two women who will recall similar instances of alleged abuse by Teron against them when they were the current victim’s age or a little older, in Puerto Rico, in the 1980s.

The prosecutor called “striking” the similarities between the alleged abuse in Puerto Rico decades ago and the alleged abuse reported by the girl in 2021.

The trial is expected to last all week, in part because a key defense witness–Barry Crown, a psychologist–cannot testify until 4 p.m. on Friday. He will put in words the defense’s central strategy: that Teron is not a pedophile, that the child may have either formed false memories or is accusing Teron in a form of defensive transference, because she may be abused by someone else whom she doesn’t want to get in trouble, and that children tell lies.

Doing so, the defense will have to navigate a very tight rope of making controversial, unprovable claims clothed in the doctorate of an expert witness while risking to shame or accuse the alleged victim.

The day-long jury-selection process, reminiscent of the selection process in the Dykes case, was a trial in itself for some of the prospective jurors. One of them had a panic attack during the lunch break. Another one said she was bawling in the bathroom during a break, and was seen crying in court. Others, victims of sexual assault themselves as children or adults, or parents of children who were assaulted, said they could not listen to testimony about such a case and keep their composure.

“I think he has a right to a trial but I don’t want to be a part of it,” one of the prospective jurors told the court, recalling her own experience with rape. “I was not believed by family,” she said. “I don’t think I can have my mind straight.” She was excused.

Another recalled how her teen-age daughter had been the victim of rape by another minor years ago in what she described as a mishandled case. “I’m pretty sure that my emotions will be involved heavily,” the woman said. “I get so emotional about the people who harm young ladies, maybe older ladies, it doesn’t matter, it still affects me a lot.” The mere word “rape” was a trigger for her. She was excused.

A police officer was excused for being openly prejudiced against those accused of sexual abuse, even before hearing the evidence. His reason: lawyers can manipulate juries away from the truth. Yet another juror was excused as much because she had a mother’s day giff lined up in the form of a plane trip to the Midwest during trial week as because she felt she’d been biased by reading a previous article about the case in this publication.

“I don’t want to listen to the details, I don’t want to listen to the testimony, I don’t want to be a part of it,” the juror who had become emotional in the bathroom and in the courtroom told the defense attorney during his portion of the proceedings.

“If you were Mr Teron, would you want you on this jury?” he asked her.

“Probably not,” she said. But she also sharply challenged him when he implied that children could lie when making allegations of sexual abuse. “I don’t think they can make that up out of thin air,” she said. “You don’t think about that stuff as a kid.”

She was unwittingly signaling to the lawyer how high risk one of the dense’s strategies will be: it let on in a pre-trial hearing that it would suggest that the alleged victim, at 7 years old, may have been “oversexualized,” in the defense’s own terms, and it was bringing in an expert witness to press the point.

That’s why jury selection begins with a pool of 40 jurors and lasts for most of the day as questions by the judge, the prosecution and the defense serve to narrow the field to jurors acceptable to both sides. Including two alternates, the jury consists of nine women and five men. They included a graphic designer, a welder, a retired surgical technician, a retired truck driver, a retired non-profit manager, two processors for the state or defense companies, a construction worker, a cosmetologist, two people who worked in or with insurers, a retired nurse manager, a hospitality industry worker, and a retired new-economy salesperson. The jury appears to include one or two naturalized citizens.

Twelve-member juries are required in capital cases, even though Teron is not eligible for the death penalty. If found guilty, he faces mandatory life in prison without parole. He turned down the deal Assistant State Attorney Melissa Clark had offered and repeated before the jurors walked in: reducing the two rape charges to attempted rape, and the capital felonies to first-degree felonies, like the molestation charge. Those would still add up to a maximum of 90 years, if served consecutively. The state was offering a maximum of 25 years. That would still add up to a life sentence for Teron, who would not be eligible for gain time, or early release. He would have to serve the sentence day for day until he is about 84, if he survives the brutality of the Florida prison system, and the brutalities inflicted on the system’s sex offenders.

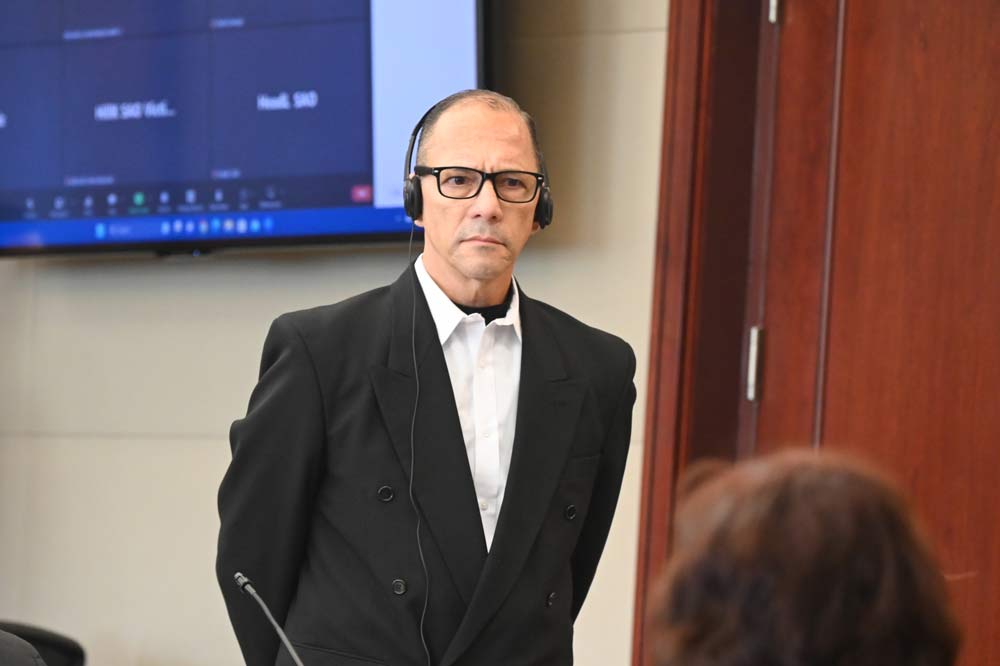

Teron sat with his two attorneys, listening to the proceedings with a headset on as a simultaneous translator interpreted from the opposite end of the courtroom, speaking at a low volume into a device. Unlike some defendants, Teron was not much involved in the selection process when it came time to strike jurors. A few members of his family sat in back of the room through the proceedings.

The case is being prosecuted by Assistant State Attorney Melissa Clark before Circuit Judge Terence Perkins. Harley Brook and Derek Maines of Cape Coral-based Musca Law are defending Teron.

It was clear that the defense lawyers were not on their home turf, much as Perkins tried to make them feel comfortable. Brook, who alone engaged with the jurors today and overthrew his pitch for likability, seemed at times jarringly off key with humor that matched neither setting nor audience. Many jurors had already spoken of their traumas and discomforts by then, and still he struck them with odd analogies about not having to prove anything (“I could be sitting here doing crossword puzzles,” he said) or joking about how “attorneys never tell the truth.”

Ironically, Brook rhetorically asked the jurors what most attorneys ask during jury-selection when they’re trying to gauge to what extent jurors associate a case with the attorneys arguing them: “I don’t like that Harley guy. He just rubs me the wrong way. Would you hold that against my client?” Brook said.

“No,” the jurors intoned in chorus–a lie, of course, as all seasoned lawyers know: personalities play an outsize role in the courtroom as does the likability of lawyers or witnesses: “as is often the case in criminal justice,” Lawrence Friedman wrote in Law in America, “in the end it was not the science, but the gut feeling of the jurors that counted.”

Clark doesn’t joke or ingratiate herself with juries. She tends to let her seriousness–and the evidence–do the gut-punches.

![]()

Ray W. says

What a rich variety of issues posed by the article. Thank you, Mr. Tristam. I wish to comment on one of the issues.

Yes, jurors often intone on cue that they will not hold their dislike for an attorney, the mouthpiece for the client, against the client. Yes, jurors may not have thought through their thoughts when they intone what they intone, or they may actually be lying when saying what they say. But when asking jurors that question, seasoned lawyers may be doing so from an understanding of the three facets of persuasion: Logos, Pathos, and Ethos.

Logos is the Greek root term for logic. A logos argument is, simply, an appeal to logic, or reason, or both. A logos argument relies on logical and clear connections between ideas, often using facts and statistics. One can employ analogies to form a logos argument, either historical or literal. Logos gaps, referred to as logical fallacies, can arise from wrongful assumptions. One common logical fallacy employed by certain FlaglerLive commenters involves trying to connect Democratic policies with communism. Yes, the Chicago Tribune once published an editorial proclaiming that the newly passed Social Security Act was a communist plot to undermine America. It was a logical fallacy then and remains so today. “That defies all logic and reason” is a phrase that can be used to expose or describe a logical fallacy. It acknowledges the three forms or reasoning that comprises Western rational thought: Deductive reasoning, inductive reasoning, and argumentation, also commonly referred to as legal reasoning.

Ethos as a persuasive tool is an appeal rooted in the presenter’s credibility or authority. Such a presenter must be qualified to comment on a particular subject-matter, either via personal experience, use of credible sources, employment of appropriate grammar, or by fair presentation of the issue, including possible counter issues or arguments. Unlike many FlaglerLive commenters, I often characterize myself only as a curious student, nothing more, as certainly not as an expert on many issues. I often use soft terms, such as possible, perhaps, maybe, or sometimes. Or I often pose issues in the form of questions, so that a reader may draw his or her own conclusions, accepting or rejecting my ideas. This was the most commonly used form of persuasive arguing that would provoke my mother to declare that the commenter was talking to hear his head roar. Dennis C. Rathsam often evokes memories of my mother talking about head roarers. For that, I thank him.

Pathos as a persuasive tool is an appeal to an audience’s emotions. Such a presenter often uses deliberate word or phrase choices, or mentions meaningful language, in hopes of provoking emotional responses, e.g., empathy, sympathy, humor, frustration, horror, or even hatred, in an audience. This tool is used to incite mobs and insurrectionists. Can it be argued that a local Republican politician’s statement during a radio program asking when could the beheading of Democrats begin was uttered in hopes of provoking the emotion of hatred?

For Real says

Lock him up for life, and sorry they won’t allow all the other cases be presented to this jury.