And on the eighth day, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers recreated the beach.

The beach renourishment project that started in Flagler Beach last month after almost 20 years of planning and waiting is nearing completion at remarkable speed, with operations moving to the area of the Flagler Beach pier and north of it starting in the middle of next week and windup expected this month.

The project is little short of the recreation of earth: 3.6 miles of shoreline that erosion, storms and climate-change-induced sea rise had reduced to a thin ribbon of rock and sparse coquina sand is being rebuilt into a wide beach that pushes the surf back the length of a football field, rebuilds sloping dunes the size of small hills and packs enough new, gray-white sand for a few years’ worth of protection, even as it is almost all expected to wither away again over time. But it is also buying the county time against the inevitable.

The contrast between the completed segments to the south of the project, starting at Flagler Beach’s water tower (see the video below this paragraph), and the eroded segments north of the construction zone is astonishing, like the metaphorical difference between days of creation, but more tangible–between the days when there was no land, and the days when there is. The completed zones are slowly being reclaimed by sunbathers, beach walkers, shell-scroungers and people seizing up in the feat. The construction zone has been one of Flagler County’s more popular tourist spots. It is worth gawking at.

There, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and its contractor, New Jersey-based Weeks Marine, are running a 24/7 operation as tons of sand is being dredged from the bottom of the sea 11 miles off shore, shipped close to shore in two shuttling dredges, slurried to land through a colossal pipeline, then leavened into the new beach with a mastodon-sized machine and a fleet of bulldozers that never rest.

If you can’t make it out there to see for yourself–the walkovers are as good as loge seats to watch the works, and Weeks Marine’s safety officers are always courteous and accommodating, up to the permissible point of viewing–what follows is an illustrated step by step description of the operation, with images and video. The technical information was provided at FlaglerLive’s request in detailed responses by Jason Harrah, Army Corps’ project manager on this particular renourishment for a decade and a half.

Congress appropriated 65 percent of the project’s initial cost. Flagler County’s former engineer, Faith al-Khatib, secured state funding to cover the county’s match. The County Commission signed a 50-year agreement that calls for renourishments of equal size at least every 11 years, though it is more than likely that the beach will need renourishing faster than that.

But the cost for each of these renourishments will have to be split 50-50 between federal and local appropriations. The federal government is committed. Flagler County is still looking for ways to pay for future renourishments. A recent attempt to institute a special tax on all county residents to that end failed. If resistant residents were to have a look for themselves at the beach’s rebirth, they might be a little less resistant.

It all begins 11 miles offshore.

Weeks Marine won the $27 million contract to rebuild 3.6 miles of beach, from North 6th Street to the northern edge of Gamble Rogers State Recreation Area. The company is using two of its fleet of 21 dredges, the R.B. Weeks–built at a shipyard in Panama City, completed in 2023 and named for the company’s co-founder, Richard B. Weeks–and the identical Magdalen, named for Richard’s wife and in service since 2017. Each is 356 feet long, almost 80 feet in width and 27 feet high, with a hopper capacity for 8,550 cubic yards. That’s equivalent to 560 truckloads. Each dredge has a fuel capacity of 220,000 gallons of diesel. A crew of 28 work 12-hour shifts on each dredge, with some 40 land-based workers working 12–hour shifts, including surveyors and office staff.

The R.B. Weeks and the Magdalen shuttle back and forth between the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s borrow pit 11 miles offshore, where Flagler County has an authorized lease on 2.5 million cubic yards of sand. The Bureau, a division of the Department of the Interior, has leases totaling 52 million cubic yards of sand for 14 renourishment projects that have been completed since 2020, are under way or are starting soon. Nine of those projects are in Florida. Texas, Maryland and

It takes each dredge an hour to make the round trip from near shore to the borrow pit. There, the dredge’s hydraulics “make use of centrifugal pumps for at least part of the transport process of moving the dredged materials, either by raising material out of the water or horizontally transporting material to another site,” Harrah says. “Typically a hopper dredger is equipped with one or two suction pipes to which the drag heads are attached. A drag head is often compared to a giant vacuum cleaner. The suction pipes are lowered underwater and the drag heads are ‘dragged’ over the seabed, sucking up material as the ship slowly moves forward, that is, trails,” as in the illustration of progress below:

Each dredge typically fills with up to 7,000 cubic yards of sand. Once fully loaded, the vessel sails to the unloading or placement site where the dredged material is offloaded. That can be done in a variety of ways, whether by opening the ship’s hull and dropping the sand, propelling it with heavy-duty pumps into the air in a process called rainbowing. (You can see an animation of those methods here.) In Flagler, the sand in the hopper is connected to the pipes under water and pumped onto the beach via slurry. There are no chemicals in that slurry. Just seawater.

The pipeline is rests on the sea floor and is approximately 4,000 feet long. The part you see floating is typically near the hookup point. If the pipeline gets clogged–it’s rare, but it happens–it’s flushed with water or fixed just as a plumber would fix a clog pipe in your home.

The slurry is piped along ever-lengthening stretches of beach as the pipe crosses completed segments, until it reaches the workhorse of the operation, that mantis-like hulk known as an extractor, as in the video below:

As Harrah explains it, the extractor is essentially a large screening device that separates any unsuitable material greater than three-quarters of an inch from the sand before the sand is deemed shore-worthy and leveled by bulldozers. The extractor–also called a Fluidized Rock System–is connected directly to the subline pipe. “These machines are used up and down the eastern seaboard for beach projects to remove these types of unsuitable material that exists on the ocean floor in some areas,” Harrah says. (You can read an entire brief on screening dredged materials here.)

The slurry mix goes through a series of screens and shakers along a conveyor belt to separate the unsuitable beach material. This could include woody debris, glass, metallic objects, and other things from the seafloor–hopefully not munitions or unexploded ordnance: if that turns up, it could shut down the operation for a while as the material is analyzed and safety assured.

Once the unsuitable material is separated into baskets, it gets further screened by trained technicians to remove all unsuitable items minus seashells. The seashells that remain are safely placed back onto the beach in the fill material along the surfzone. The debris that doesn’t make the cut is hauled off to a certified landfill.

The extractor is remote controlled and moves up the beach as bulldozers ahead of it have filled in the space with new sand, which gets dumped on the beach at a rate of 1,500 cubic yards per hour, or 36,000 cubic yards per day, with no let up. The underwater pipeline, or subline, will periodically be moved up the beach as the project progresses, as it has already a few times.

For the fleet of bulldozers, it’s a different challenge. They have to translate sand elevations as designed on paper to proper sand elevations on the beach. The Corps has to ensure that Weeks Marine’s crew builds the beach berm and the dune to the design required for tides, storm surge, sea level rise, and so on. GPS ensures the work is completed as designed. The bulldozers take a beating and have to be recycled every three to five years, but like retired athletes who turn to coaching, the dozers can put in another 10 years on land-based operations.

“Public safety is also paramount on these jobs. People by nature are excited, curious of the work so ensuring the public doesn’t enter active work zones or damage newly constructed dunes by walking or digging for shells is a key aspect,” Harrah said.

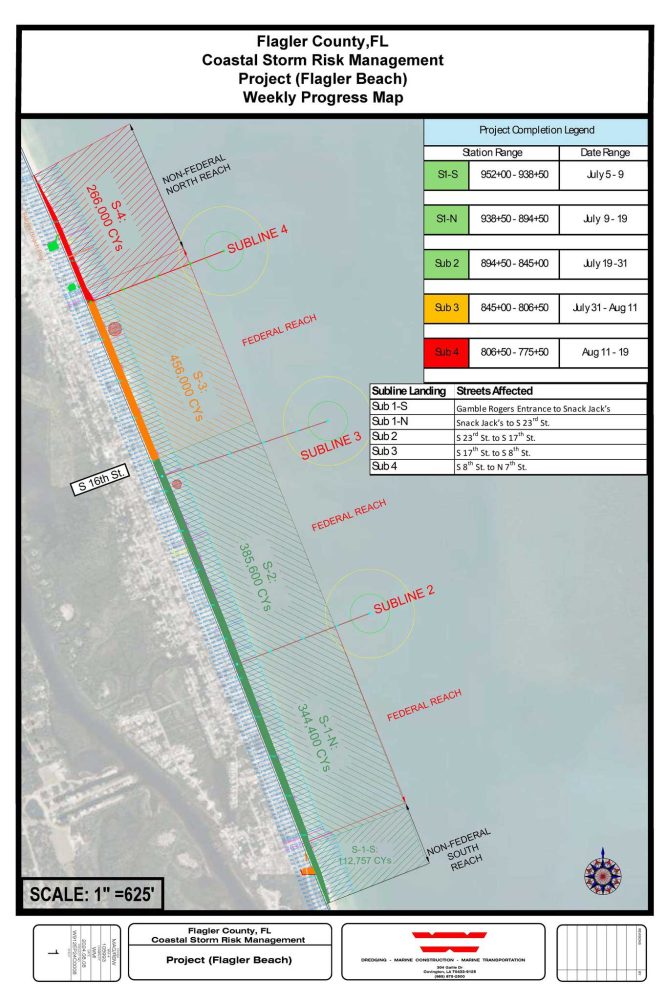

The project is well over halfway done: as of two weeks ago it was already 53 percent done, with 850,000 cubic yards of sand dropped on the beach, and of course a lot more since as it nears its completion date very possibly later this month. By the time it’s completed, it will have dropped a total of 1.6 million cubic yards of sand–1.34 million cubic yards on the federal portion of the project and 260,000 cubic yards on the non-federal portion Flagler County is assuming.

While the average renourishment interval is 11 years, the Corps will monitor the project closely every year in coordination with Flagler County, advancing or delaying the timeline depending on how the beach is doing. Don’t be surprised, or alarmed, if you see erosion happen almost before your eyes, as some did after Hurricane Debby’s storm surge passed through last week, taking out a chunk of new sand.

“Typically the first and second renourishments erode faster as the beach template fills up immediately offshore,” Harrah said. “That is to be expected. Some of our larger more successful beach projects like St. Augustine Beach, Duval County Beaches have been renourished since the 1980s and over time, we have built projects that can withstand the force of large storms with minimal damage.”

![]()

Celia Pugliese says

Thank you Flagler Live Pierre for this incredibly documented videographic editorial!! Maybe makes us more prone to rethink a beach renourishment contribution.

Shark says

Better get there to see it soon because it will be gone in a few months if not weeks.

Janet Sullivan says

Fascinating. Thank you.

Mister BAILEY says

[Comment disallowed. Do not use this site to spread disinformation. Thanks.–FL]

Brian says

Wow – great article! I go and watch this engineering marvel every day, and this detailed presentation makes it even more interesting! I live on 5th Street North and anxiously await their arrival to the “north end”!

Lance Carroll says

Has a “surf zone” been set up for local surfers around Pier area? If not, how will local surfers know the rules that should be abided by? One can’t expect to know the rules while the rules are not put out to the public..

Any documented rules as to the mean tide line? The surfers want to know how they might be in violation of enjoying a traditional Flagler Beach past time…

Tamgo says

Climate change? Sure.

stephen bradley says

Now the problem is how do we keep our dunes intact and hopefully restore them. The sand won’t hold without vegetation, and the vegetation won’t grow unless people stop walking in areas they should not be. In the past week I have seen people setting up shelters on the dune, collecting shells, and generally doing stupid stuff. Do we need to educate people on how this fragile ecosystem works. Perhaps PSA spots on the local channels. The other option is to regularly enforce the fines for parking and otherwise doing damage. It would take a full time position just to do that. There is an answer just not sure what it is???