By Mariah Meek

The largest tract of public land in the United States is a wild expanse of tundra and wetlands stretching across nearly 23 million acres of northern Alaska. It’s called the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, but despite its industrial-sounding name, the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, or NPR-A, is much more than a fuel depot.

Tens of thousands of caribou feed and breed in this area, which is the size of Maine. Migratory birds flock to its lakes in summer, and fish rely on the many rivers that crisscross the region.

The area is also vital for the health of the planet. However, its future is at risk.

The Trump administration announced a plan on June 17, 2025, to open nearly 82% of this fragile landscape to oil and gas development, including some of its most ecologically sensitive areas. The government is accepting public comments on the plan through July 1.

I am an ecologist, and I have been studying sensitive ecosystems and the species that depend on them for over 20 years. Disturbing this landscape and its wildlife could lead to consequences that are difficult – if not impossible – to reverse.

What is the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska?

The National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska was originally designated in 1923 by President Warren Harding as an emergency oil supply for the U.S. Navy.

In the 1970s, its management was transferred to the Department of Interior under the Naval Petroleum Reserves Production Act. This congressional act requires that, in addition to managing the area for energy development, the secretary of the interior must ensure the “maximum protection” of “any significant subsistence, recreational, fish and wildlife, or historical or scenic value.”

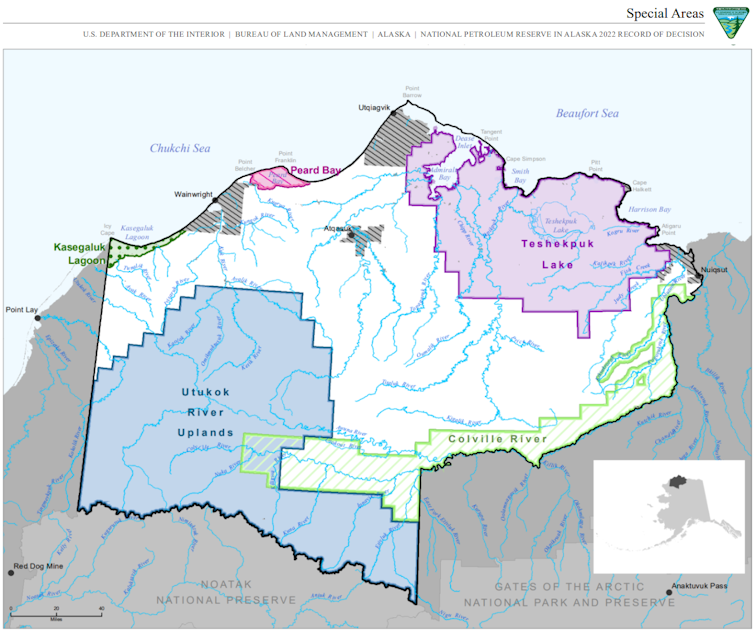

The Bureau of Land Management is responsible for overseeing the reserve and identifying and protecting areas with important ecological or cultural values – aptly named “special areas.”

U.S. Bureau of Land Management

The Trump administration now plans to expand the amount of land available for drilling in the NPR-A from about 11.7 million acres to more than 18.5 million acres – including parts of those “special areas” – as part of its effort to increase U.S. oil drilling and reduce regulations on the industry.

I recently worked with scientists and scholars at The Wilderness Society to write a detailed report outlining many of the ecological and cultural values found across the reserve.

A refuge for wildlife

The reserve is a sanctuary for many Arctic wildlife, including caribou populations that have experienced sharp global declines in recent years.

The reserve’s open tundra provides critical calving, foraging, migratory and winter habitat for three of the four caribou herds on Alaska’s North Slope. These herds undertake some of the longest overland migrations on Earth. Infrastructure such as roads and industrial activity can disrupt their movement, further harming the populations’ health.

The NPR-A is also globally significant for migratory birds. Situated at the northern end of five major flyways, birds come here from all corners of the Earth, including all 50 states. It hosts some of the highest densities of breeding shorebirds anywhere on the planet.

An estimated 72% of Arctic Coastal Plain shorebirds – over 4.5 million birds – nest in the reserve. This includes the yellow-billed loon, the largest loon species in the world, with most of its U.S. breeding population concentrated in the reserve.

Bob Wick/BLM, CC BY

Expanding oil and gas development in the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska could threaten these birds by disrupting their habitat and adding noise to the landscape.

Many other species also depend on intact ecosystems there.

Polar bears build dens in the area, making it critical for cub survival. Wolverines, which follow caribou herds, also rely on large, connected expanses of undisturbed habitat for their dens and food. Moose browse along the Colville River, the largest river on the North Slope, while peregrine falcons, gyrfalcons and rough-legged hawks nest on the cliffs above.

A large stretch of the Colville River is currently protected as a special area, but the Trump administration’s proposed plan will remove those protections. The Teshekpuk Lake special area, critical habitat for caribou and migrating birds, would also lose protection.

Bob Wick/BLM, CC BY

Indigenous communities in the Arctic, particularly the Iñupiat people, also depend on these lands, waters and wildlife for subsistence hunting and fishing. Their livelihoods, food security, cultural identity and spiritual practices are deeply intertwined with the health of this ecosystem.

Oil and gas drilling’s impact

The National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska is vast, and drilling won’t occur across all of it. But oil and gas operations pose far-reaching risks that extend well beyond the drill sites.

Infrastructure like roads, pipelines, airstrips and gravel pads fragment and degrade the landscape. That can alter water flow and the timing of ice melt. It can also disrupt reproduction and migration routes for wildlife that rely on large, connected habitats.

Networks of winter ice roads and the way exploration equipment compacts the land can delay spring and early summer thawing patterns on the landscape. That can upset the normal pattern of meltwater, making it harder for shore birds to nest.

Kyle Joly/NPS

ConocoPhillips’ Willow drilling project, approved by the Biden administration in 2023 on the eastern side of the reserve, provides some insight into the potential impact: An initial project plan, later scaled back, included up to 575 miles (925 kilometers) of ice roads for construction, an air strip, more than 300 miles (nearly 485 kilometers) of new pipeline, a processing facility, a gravel mine and barge transportation, in addition to five drilling sites.

Many animals will try to steer clear of noise, light and human activity. Roads and industrial operations can force them to alter their behavior, which can affect their health and how well they can reproduce. Research has shown that caribou mothers with new calves avoid infrastructure and that this impact does not lessen over time of exposure.

Simon Bruty/Anychance/Getty Images

At Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay, the largest oilfield in the U.S., decades of oil development have led to pollution, including hundreds of oil spills and leaks, and habitat loss, such as flooding and shoreline erosion, extensive permafrost thaw and damage from roads, construction and gravel mining. In short, the footprint of drilling is not confined to isolated locations — it radiates outward, undermining the ecological integrity of the region. Permafrost thaw now even threatens the stability of the oil industry’s own infrastructure.

Consequences for the climate

The National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska and the surrounding Arctic ecosystem also play an outsized role in regulating the global climate.

Vast amounts of climate-warming carbon is currently locked away in the wetlands and permafrost of the tundra, but the Arctic is warming close to three times faster than the global average.

Roads, drilling and development can increase permafrost thaw and cause coastlines to erode, releasing carbon long locked in the soil. In addition, these operations will ultimately add more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, further warming the planet.

The public comment period on the White House’s plan to open more of the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska to oil and gas drilling closes at the end of the day on July 1.

The decisions made today will shape the future of the Arctic – and one of the last wild ecosystems in the United States – for generations to come.

![]()

Mariah Meek is Associate Professor of Integrative Biology at Michigan State University.

Ray W. says

According to stories released by Oil Price US and by KDLL, a Kenai Peninsula radio news outlet, this coming December will see an auction of nearly 80 million acres of offshore Gulf seafloor, split into 14,000 tracts, plus an auction of an unreported number of Cook Inlet, Alaska parcels. Instead of the recent “standard” 18.75 percent royalty rate that is to be paid to the government on whatever oil or natural gas that is extracted from each tract, bidders will be offered a less than standard royalty rate of 12.5 percent. The minimum auction bid will be $25 per acre, regardless of whether the tract yields oil or natural gas.

According to the KDLL reporter, auctions held during the previous administration drew an “under-subscribed” number of bidders, meaning there was relatively little interest from oil extraction companies was drawn to the bidding process.

The December auction is the first of at least 30 Gulf sales to be set over a multi-decade schedule, and six Cook Inlet sales through 2032, as released by the Department of the Interior.

Make of this what you will.

Me?

I recently commented on three recent coal auctions held by the Bureau of Land Management.

The Alabama auction for “coking” coal, a specialty type of coal crucial for our steel industry, drew interest and a $1.10 per ton bid, a bid that was accepted as being one of “fair market value.”

The Montana auction for electricity generating coal drew a single bid of one-tenth of one penny per ton of coal, a bid that has since been suspended on the ground that it is below “fair market value.”

The Wyoming auction for electricity generating coal drew one bid for less than one penny per ton, a bid that was not accepted and the bidding process was suspended.

I have repeatedly commented that high percentages of the overall acreage of many of the shale oil basins, such as the Permian and the Bakken, are privately owned. So long as oil can profitably be extracted at low cost from wells drilled on privately owned land, leases for the right to drill on publicly owned tracts of lands that are remote from highways, rail lines and pipelines, are relatively too expensive to exploit.

Quite a lot of noise has been made by the professional lying class that sits atop one of our two political parties about how coal, crude oil, and natural gas are the future of America’s energy marketplace.

But when auctions for coal bring few bidders and when those few bidders offer extremely low bids on coal that is useful for electricity generation, and when the government lowers the standard royalty rate by nearly one-third, arguably to entice bidders on undersea crude oil reserves, something tells us all that the promises made during an election season were not as truthful as they seemed to be at the time they were made.

As an aside, but because the reporter used the phrase “undersubscribed”, I looked up the number of companies that bid on the most recent sale of undersea leases in the Gulf.

According to a Natural Gas Intelligence site, presumably an industry journal, in December 2023, the Interior Department’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management held “Lease Sale 261” on 13,500 unleased tracts on nearly 73 million acres of Gulf undersea areas.

The minimum bid price per acre for that sale was $25 per acre for tracts less than 400 meters below the surface and $100 per acre for tracts in depths greater than 400 meters below the surface of the water.

Twenty-six companies bid more than $382 million for 311 of the 13,500 tracts, meaning more than 13,200 of the tracts did not attract a bid. As an aside, according to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, a standard lease obtained by high bid lasts five years, with a potential of a three year extension.

Admittedly this is an estimate based on the vague numbers and explanations contained in the article, but roughly 73 million acres divided by roughly 13,500 tracts yields roughly 5400 acres per tract. Multiply 5,400 by 311 and you get 1,679,400 acres, again, as a rough estimate. $382 million in accepted bids divided by that acreage yields an average $227.46 bid per acre, over ten times the government’s minimum bid price per acre set in 2023 and also set for this upcoming December’s sale.

December will soon be upon us. Perhaps I will stumble upon an article about the interest drawn by the December sale and the willingness of energy extractors to spend money on locking in undersea tracts for possible future exploration.

Pogo says