Brian Keith Johnson is a 22-year-old Gainesville man who was arrested in Flagler County, along with two other men, 13 months ago. They’d stolen a car in Gainesville and crashed it into a Penske truck on U.S. 1, just north of Royal Palms Parkway in Palm Coast, after a brief chase. Johnson was charged with grand theft auto and fleeing and eluding. He went on trial Monday.

The trial would not have ordinarily drawn much public attention for those charges. This one did. It was the first in-person jury trial in Flagler County and the four-county Seventh Judicial Circuit since March, and it is “believed to be the first in Florida since the onset of the covid-19 pandemic,” according to Mark Weinberg, the Seventh Judicial Circuit’s court administrator.

But it wasn’t quite in person–if by in-person one includes the public. It was Zoomless only for those involved in the trial: Circuit Judge Terence Perkins, clerks, the lawyers, the defendant, a couple of bailiffs (as opposed to the platoon that occasionally gathers at such trials), and jury of six plus two alternates, seated in every third chair in the jury box. The public was not allowed, nor was Johnson’s father, nor were reporters.

When it was over with a jury verdict at 7:10 p.m., after just over two hours of deliberations, the jury found Johnson guilty on both counts of grand theft and fleeing and eluding. The deputy clerk wasn’t done reading the verdict before the sound of bailiff Brian Sheridan’s handcuffs sounded as they ground around Johnson’s wrists, out of view of the camera, as he had been throughout the trial. He is to be sentenced in six weeks. He faces a maximum of 20 years in prison, but will likely get considerably less since he’s not a repeat offender.

The trial was webcast through YouTube, though much of the morning’s webcast was hampered by buffering issues that made following testimonies difficult. Just after 5 p.m., the feed cut off inexplicably, just as Perkins was finishing instructions to the jury before sending them off to deliberate. The YouTube Channel’s screen was replaced by a line fit for Kafka’s “Trial”: “This channel doesn’t have any content,” though Johnson’s fate was in the jury’s hands and the verdict was expected this evening. (The feed had previously continued even when the courtroom was empty, but in this case it cut off as the jury deliberated.)

By then the trial video had accumulated 168 views–more by far than the number of spectators who usually attend a trial in person. That figure usually is close to zero, except when family members or lawyers and cops drop in.

Today’s viewers included Johnson’s father and one of the two other people who were in the stolen Mitsubishi SUV with Johnson that July 14, 2019, when it crashed: Justin Thomas Edward-King, who at one point this afternoon–immediately after the defense rested–messaged Johnson’s father, who emailed Bill Bookhammer, one of the public defenders, to tell him that Edward-King was now ready to “help” Johnson and testify. Edward-King had been reluctant because he has a warrant out for his arrest on an unrelated incident. He had been charged for grand theft a year ago, but the charge was dropped.

Assistant Public Defender Bill Bookhammer argued for a continuance. It was too late.

“Is he going to say he’s the driver?” Perkins asked Bookhammer.

“We have not been able to get in touch with Mr. King directly,” Assistant Public Defender Steve Gosney said. “Obviously this would be powerful exculpatory evidence for our client.”

“When you say this, you mean what?” the judge asked. Gosney said that has to be explored.

“Based on what we know, which is very little, I’m denying the motion for a continuance,” the judge said and moved on to closing arguments.

Johnson is not exactly Joseph K. Much about the case is known: he concedes being part of the trio that stole the car from a Gainesville dealership three days earlier. There’s no question that he was in the car that a license plate reader flagged in Flagler that July 14, that Flagler County Sheriff’s deputies set chase, among them Sheriff Rick Staly himself (he didn’t chase so much as spot the car as he was himself driving on U.S. 1).

“I’m familiar with what’s going on, very much familiar with what’s going on, and they do black men like this all the time. They stereotype them,” Brian Johnson Sr. said Tuesday morning outside the courtroom. He’d shown up with a camera on top of a tripod, which he was using to video himself in live feeds of his own about the trial. He said he’d been incarcerated himself until his sentence was “corrected” and he was released.

Car theft is a third-degree felony with a maximum prison term of five years. Fleeing and eluding police is a second-degree felony that carries a maximum punishment of 15 years in prison. The two-day trial hinged on that factor: who was at the wheel? There was conflicting testimony between two deputies, and there was DNA and fingerprint evidence on the driver’s side door, unsmudged, that indicated one of the other two people in the car had last opened the door–not Johnson, though the prosecution argued that the three had taken turns driving.

“You may think you saw something but it’s not true,” Bookhammer told the jury after pointing out a series of inconsistencies in deputies’ statements. He spoke of instant replay in sports. “Referees are trained observers. They’re not involved in high-speed chases, driving down the road at 80 to 100 mph, having to process a million things and a million possibilities going through their mind as things unfold in front of them. They’re the best of the best, and they get it wrong. But an officer gets something wrong in a criminal trial, and the jury accepts it as true, the consequences are devastating.”

Bookhammer sought to establish reasonable doubt that Johnson was at the wheel, telling the jury that it would find him guilty only by discounting the entirety of another deputy’s testimony and the DNA and fingerprint evidence on the driver’s side door. He argued that the sheriff’s investigation had been incomplete.

“All of that evidence all of that testimony tells you that this defendant was driving on that day, and consequently you will convict him as charged,” Bavington, the prosecutor and a new face at the Flagler courthouse, told the jury. (The jury was kept invisible in the YouTube webcast, to protect its anonymity.)

“What were they doing there? I have no idea. But the three of them were there together. The three of them were in this stolen car, together, on July 14,” Bavington said. “Absolutely, these fingerprints and DNA would be important if not for the fact that we know, this car was stolen three days prior, by these three individuals that were in the car. Reasonable to assume they all would have changed positions.” At that point, of course, Bavington was doing precisely what the defense argued the state had been doing all along: indicting Johnson by inference and melding the two charges–grand theft and eluding–into one, and playing on the jury’s susceptibility to doing the same.

Johnson for his part tried to flee the car after the crash, the prosecutor said. “Those aren’t the actions of someone who was along for the ride, those aren’t the actions of someone who doesn’t know what was going on.” Rather, he said, that was “evidence of his guilt”–though as even courts have recognized, fleeing from police is not necessarily evidence of guilt (a Black man “might just as easily be motivated by the desire to avoid the recurring indignity of being racially profiled as by the desire to hide criminal activity,” Massachusetts’ highest court ruled four years ago).

But the evidence as the prosecution framed it was too much for the jury to overcome and go with Bookhammer’s case.

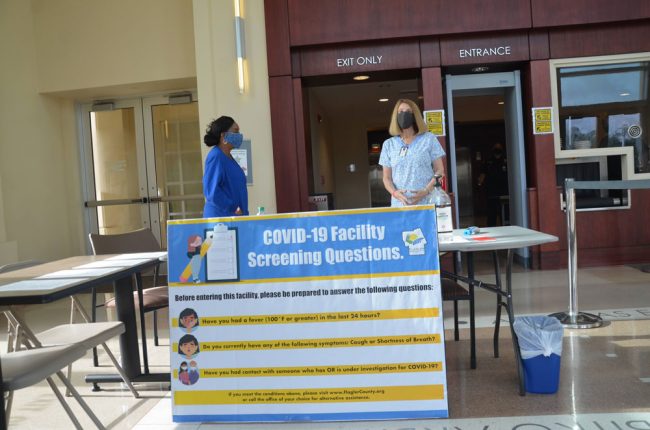

The courtroom had been slightly reconfigured to ensure social distancing. The judge’s clerks and court reporter usually sit at significant distances from each other anyway, but today they were masked, as was the judge, as was anyone in the courtroom (no exceptions, even while speaking), and the court reporter wore a plastic face shield. Perkins used a hand sanitizer liberally. The lawyers had fleeting moments of frustration.

“Boy, this is killing me, phew, Sorry, I have breath problems,” Gosney said at one point, as he was arguing for a ruling. The jury was not in the room at the time.

“And it’s hard talking in a mask, unquestionably,” Perkins said. “It’s part of the most difficult part of this trial.”

“I’m having to take breaks, Sorry,” Gosney said.

“Take as many breaks as you need,” the judge told him.

He was not to need another.

The Florida Bar reported on Tuesday that the trial “the trial was the result of a month-long effort by local court officials, the local Health Department, the Supreme Court, and others and made possible by a low number of coronavirus infections in Flagler County.” The county’s infection rate is lower only relative to that of other Florida counties, but remains high when compared to many other states or countries. “Resuming jury trials is an important milestone for Florida’s courts and the people we serve,” Chief Justice Charles Canady was quoted as saying. “Chief Judge Raul Zambrano and Circuit Judge Terence Perkins prepared carefully for the safe conduct of this proceeding in Flagler County, along with all the justice partners involved. I appreciate the care taken to follow evidence-based best practices for this trial and elsewhere around the state as courts continue to work diligently.”

A FlaglerLive reporter was not allowed to stay after taking a few pictures before the jury walked in this morning, and a News-Journal reporter later in the day was turned away at the courtroom door. That was unexpected: when Chief Judge Raul Zambrano issued orders closing most court functions in spring, he made an exception for the press to attend whatever usually public proceedings would take place, even if the general public was excluded. (It appeared in late afternoon that Zambrano, who was not aware of the exclusion of reporters, would ensure that the press would not be excluded in the future.)

At the very end of the trial, Perkins thanked the jury for serving in exigent circumstances. “I want to thank you on behalf of the court system for your community service and your patriotic service to your community,” Perkins said, telling them the system wouldn’t work without them under normal circumstances. “But these are not normal times. I think you heard that this is the first of the trials that we’ve had since we closed down for covid. I’m told that’s true, I don’t know if it is, but I’m told that it is. And I think that took a particular level of commitment to your community and courage, and I wanted to let you know that I recognize that and I thank you for that.” He told them that “if you can think of anything that we can do better” to improve the experience and make it “as safe a process as we can,” to let him know.

![]()

C’mon man says

Sounds like this kid needs to man up. The it wasn’t me story is getting old.

really says

At least two out of three wont be stealing cars for the time being. Attending criminal graduate school in prison.