By Fauzia Husain

On Feb. 25, United States Air Force member Aaron Bushnell set himself on fire outside the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C.. The 25-year-old, who was in uniform, live-streamed what he called his “extreme act of protest against the genocide of the Palestinian people.”

His startling and fatal act quickly went viral on social media while the public, and his friends and family have struggled to make sense of Bushnell’s painful sacrifice. How can we begin to make sense of such an extreme act? And, will his actions have any impact on public opinion?

While undeniably remarkable, Bushnell’s actions begin to make a little more sense when seen in broader context. Self-immolation, the act of setting oneself on fire, can be seen as an extreme form of a modern repertoire of protest that is both common and familiar, not just in the U.S. but in many parts of the globe.

For example, in my research with frontline women workers in Pakistan, I found self-immolation was part of a broader set of attention-grabbing tools women used in an effort to attract both attention and allies for what they saw as an otherwise lost cause. I call this broad set of publicity seeking efforts “spectacular agency,” a set of stunning dramas people stage to publicize abuse, critique injustice, censure abusers and protect the vulnerable.

Spectacular agency

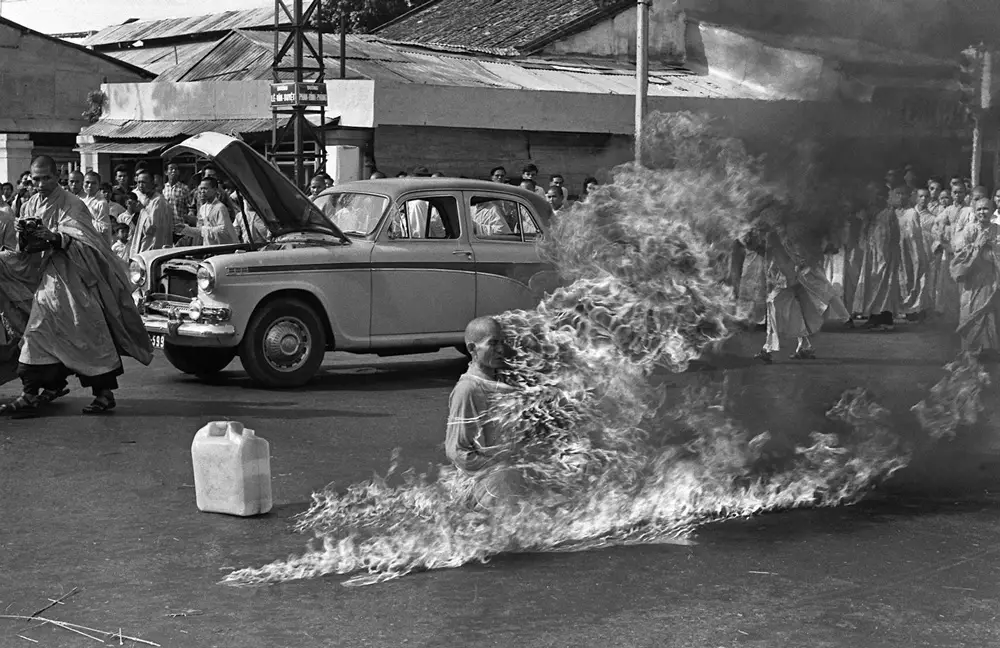

Spectacular agency, including extreme forms like self-immolation, is not new. Many people from the 1960s generation will be familiar with the photograph of Thich Quang Duc, the Buddhist monk who self-immolated to protest the South Vietnamese government’s persecution of Buddhists. His unthinkable gesture brought international attention to the plight of Buddhists in South Vietnam.

Now, since the advent of globalized broadcast media, such actions can quickly gain attention across the globe. Indeed, with the wider availability of social media and the possibility of going viral, such protests have become more common than you would think.

Not all spectacular actions include the extreme act of self-immolation, but many examples exist within its realm. They have included the use of hashtags like #metoo, the circulation of leaked videos, the practice of hunger strikes, the use of inflammatory posters, the burning of effigies (for example when U.S. protestors burnt their draft cards in 1965) and also attempted self-immolation.

And as I found in Pakistan, this also includes the organization of dharnas (sit-ins). Sit-ins have also been recently used as a protest technique to call for a ceasefire in Gaza at Toronto’s Union Station and in Washington, D.C. in October.

While such acts may generate attention, this kind of agency is often costly, requiring the protesters involved to make considerable personal investments of time, money, comfort, privacy, dignity and even life.

Yet, despite the costs, the outcomes of spectacular agency are frequently uncertain.

This is because spectacular agency requires recruiting others, such as audiences, who need to buy into a message, an idea or a point of view. But no matter how carefully they stage their dramatic contention, protesters have limited control over the way their vivid efforts will be read and interpreted by others.

How audiences interpret protests

When the public sees spectacular acts, they may focus on the symbols protesters use, such as military uniforms, that may be both symbolically loaded and multivocal. People invest a lot of meaning into military uniforms and they may read their use in many different ways depending on their different points of view. While symbols like uniforms can be arresting, their use may not always produce the interpretation the protester desired. Instead, the use of a loaded symbol may be taken by spectators as sacrilegious, and their use, therefore, can lead audiences to question the protester’s sanity.

The meanings audiences draw from spectacular performance, moreover, often interact with broader currents of inequality in society. An actor’s race, gender or age can be important factors that determine whether they have the authority, in an audience’s eyes, to use a particular symbol or to spectacularly tell a story that is important to them.

Women engaging in spectacular agency to draw attention to sexual assault, like the Columbia student who carried a mattress around campus to draw attention to sexual abuse, may find audiences either blame the victim or refuse to believe her account.

Selflessly fighting for a better future

In Pakistan, women frontline workers’ spectacular actions also brought mixed results. When I say frontline workers, I mean people who provide face-to-face service to citizens. One airline attendant took to social media in an effort to protest against the ageism and sexism of some passengers and found supportive and allies among other social media users.

But other women workers were not so fortunate.

Pakistani Lady Health Workers, who travelled from city to city across Pakistan engaging in long running spectacular efforts to grab attention for their poor working conditions, succeeded in getting the Pakistani Supreme Court’s attention and intervention.

However, the women then had to confront a slowly moving bureaucratic administration that found ways to delay or limit the women’s gains. Some of these women said the reforms they had worked so hard for would not benefit them directly. They were on the verge of retirement and were told by their bosses that their hard-won gains in wages and pensions would not apply to them.

Yet, most of these women said they did not regret having made the effort.

Speaking about her own inability to reap the rewards of spectacular agency, Nuzhat, a frontline health worker said:

“It doesn’t matter. The next generation will get it. One person grows a tree so that the next generation can sit in its shade…What is important is that you plant it.”

Spectacular agency is costly, requiring the surrender of money, time, comfort and also, at times privacy and dignity. Therefore, people who engage in it, often see it as an altruistic sacrifice made in the name of others.

Rehana, a health worker said:

“I don’t feel sad that I derived little benefit from that effort…I feel that you should do whatever you can do. Whatever we can do for the next generation, we do it. You can’t control the outcome, but you can say: ‘O Allah, I have fulfilled my obligations. I spared no effort to create a better world for the next people who will take my place. Now it’s up to them and you.’

![]()

Fauzia Husain is Assistant Professor at the Department of Sociology at Queen’s University, Ontario.

Samuel L. Bronkowitz says

[Please comply with our comment policy. Thank you.–FL]

It’s hard to tell if they’d make a difference or not because of the media’s insistence at using misleading headlines or the passive voice when reporting on them. It says a lot about the media establishment, this one included.

jake says

Not sure what FL is trying to say here, however, if you are a FL boot licker, you get away with much more crap, than anyone else. I realize Pierre likes to think this isn’t true, but as a long time reader, and commenter, I personally have been admonished for some of my comments, when accompanied with FACTS, when others, more “liked” get away with “murder”. Exactly which “comment policy” was violated?

Samuel L. Bronkowitz says

I see the comment policy blurb at the top of this post. I think it would be educational for myself and other people that post here to explain why.

Ban the gop says

this is florida protesting is illegal and you will be charged with a laundry list of crimes for a single offence. So not sure there’s a point to it as nothing changes with protests. Now get back to work, your owner needs a new boat.