As the attorneys made their closing arguments this morning in Brenan Hill’s trial on a second-degree murder charge, Hill compulsively wiped his palms with a white towel. When he wasn’t wiping he was folding it, unfolding it, clutching it in his fist, and rocking back and forth in his chair at the defendant’s table. His head at times nodded more obviously when his attorney told the jury a dozen times that Hill never intended to kill Savannah Gonzalez on March 26, 2021. That the shot was accidental.

It was impossible to tell whether Hill was attempting to telegraph his feelings to the jury or to convince himself of his attorney’s words.

Either way, a jury of four women and two men found Hill guilty of second degree murder and two other charges after deliberating two hours and 45 minutes today. He faces from a minimum mandatory 25 years up to life in prison when Circuit Judge Terence Perkins, who presided over the five-day trial, sentences him on Dec. 1. The verdict was announced shortly after 2:30 p.m.

A half dozen family and friends of Gonzalez sat on one side of the courtroom, taking in the verdict quietly. The group included one of Hill’s other victims, and the mother of his child. Four members of Hill’s family or friends sat at the back, on the other side, showing little emotion until Hill was ushered out a side door, back to jail. Afterward, some of Gonzalez’s family members hugged and wept.

Hill showed no emotion.

Defense attorney Gerald Bettman in his 39-minute closing argument had conceded to the jury that his client had lied repeatedly to police, that he’d said awful, hurtful and threatening things to Savannah. But he urged the jury to focus on what happened in the car, where Savannah was shot around 9:45 the morning of March 26, 2021, in the Publix parking lot on Belle Terre Parkway, a few hundred feet from Burger Bros, where she was due for a shift.

“You have to disregard the terrible scenes up there and focus on what happened at 9:45, not speculating he must have been angry,” Bettman said.

On this fifth day of trial, Assistant State Attorney Melissa Clark summed up what the jury had seen and heard in previous days to paint the picture of an angry Hill, a violent Hill, a lying Hill–not just in that moment when he fired the gun, but in his person, in his way of being. The “rage” that caused him to shoot his girlfriend–Savannah Gonzalez was 22–was something Gonzalez had feared enough when she tried to keep him from buying the gun that he used to kill her.

“She didn’t want him to have a gun, because she was afraid,” Clark told the jury. “She knew his temper. She knew what he was capable of. And she was afraid that he would kill her. And her fear was valid. Within a week of obtaining that gun, he did exactly what she was afraid of. There was no accident in this case.”

He shot her out of anger, she said, then covered up the crime with “his web of lies, the smokescreen to hide the truth,” Clark said. “It starts from day one. The minute he drops off Savannah at the hospital, we’re starting to see some of these lies.”

The lies did not stop, even, apparently, when Hill testified on Thursday and changed his story yet again from what he had told detectives five weeks after the shooting, when he owned up to what he then said was the truth: that the gun had fired by accident.

On the stand, Hill said he had his thumb on the hammer and his finger on the trigger when he was trying to unload the gun, and it just went off when his thumb slipped. To detectives, he’d said his finger was never on the trigger, only that the gun was defective. That theory was disproven by two Florida Department of Law Enforcement firearm experts. Hill watched their testimony. So he changed his story yet again. Clark easily refuted it, bringing in one of the detectives who had interviewed him at the county jail during his “confession.” The detective testified to what Hill had said then.

If anything could have undone Hill, it was his compulsive lies starting literally minutes after he pulled the trigger, when he called his own mother to lie about what had happened, telling her the story he would tell the first sheriff’s deputy he saw at AdventHealth: that a Black man had attempted to rob him, pointing a gun at him, forcing him to grab the gun, which went off and struck Savannah. Then he lied about where it happened, then he lied about how he and Savannah were short of money and were desperate to find a place to live, though the night before the shooting he’d shot a video of himself flashing a wad of cash (and the gun), and even testified that they were only $350 short of the thousands they needed to rent a place.

“We needed $3,200, we were almost there, I couldn’t give money back to people I owed it to, it would have reduced what we needed,” Hill testified. So why they were in a panic about having been kicked out of the Microtel was never made clear in light of the cash they did have.

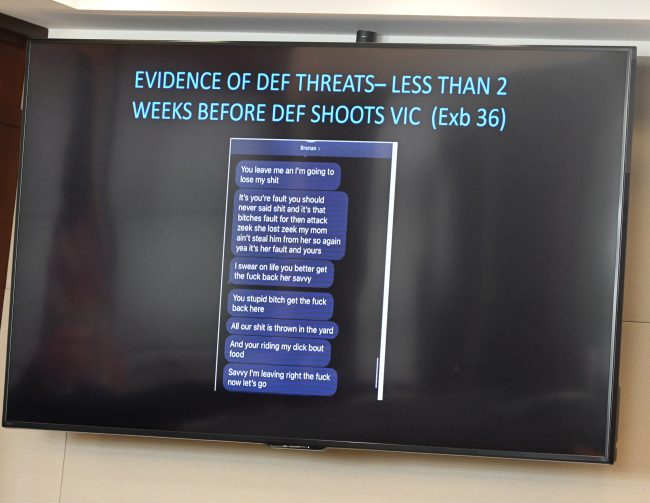

What was clearer, because it was on video that the jury saw, was that Hill had exploded with rage when Savannah objected to him buying a gun. He called her vile names, called her an idiot, called her a stupid bitch, screamed at her, and threatened her even as she spoke her fear of the gun: “Bitch if I wanted to kill you I’ll just kill you. I’ll fucking kill you,” he promised her. He wouldn’t need a gun, he boasted.

“And that’s what he did on March 26,” Clark told the jury.

What is also clearer is that he lost it again and became abusive against her shortly before the shooting when Savannah had moved his stash of drugs that he was using to traffic, to make money, and–breaking the rule of wiser dealers–use himself: he was an addict. That outburst was also captured on videos that by then Savannah was taking, as if to document his rage, as when he told her, using the abuser’s textbook blame of the victim’s responsibility for his own violence: “please don’t make me hit you.”

For all that, Bettman, Hill’s attorney, was right when he argued that speculation, not hard evidence, not proof, fills in the prosecution’s gap for what specifically happened in that car in the few hundred feet between Burger Bros and the adjoining Publix parking lot, in the few minutes between the last time a Burger Bros employee saw Hill and Samantha apparently arguing in the car, and the moment when a surveillance camera caught Hill stepping out of the car with the gun wrapped in a white towel to hide it in the bushes before speeding off to AdventHealth.

Hill’s nonexistent honesty aside, there is no video, no testimony, no forensic evidence that can irrefutably say why and how what took place in that car at that moment took place in that moment. The evidence of a shooting is indisputable. The evidence of manner and intention is not as indisputable.

The prosecution conjectured it from a morbid mass of surrounding evidence about Hill’s temper and his words, his threats and the evidence of a photographed bruise on Savannah’s chin (Hill called it a hickey), and of course his lies. But lying is not murder. It’s not even a crime. Nor is being a reprehensible human being who vilifies the person he claims to love, and calls her a loser.

Clark’s challenge was to convince the jury that the surrounding evidence left no room for doubt as to what could possibly have happened in the car–that while Hill had not planned to kill Savannah that day, he had intentionally pulled the trigger, shooting her in the base of the head. She died a year and a half later, after never recovering from the wound and living those months in debilitated state in various hospitals. The medical examiner attributed her death to the gunshot. Clark called the bullet Savannah’s “death sentence.”

Clark’s challenge was to prove something by its absence, the way astronomers prove the existence of a black hole, which is impossible to see, by analyzing its surroundings. Her challenge was to convince the jury that Hill’s nonexistent honesty was that black hole from where no truth could emerge. It was proof that everything he was saying was a lie, leaving only one possibility: he knowingly, angrily shot her.

Bettman’s challenge was to convince the jury look past the sordid character and behavior of his client and find that “this is an excusable homicide.”

“It is excusable, and therefore lawful. It’s not good. It’s bad.” But it’s not punishable, because it was “without unlawful intent.” He termed “unfair” a lot of the way the case unfolded in court: “I’m really disappointed that the state would not try to show you more of what happened in the car,” he said, drawing one of a half dozen objections from Clark, who countered that the jury saw the photographs from inside the car–58 photos, showing blood stains in every location there was blood, showing shell casings, showing a bloody pillowcase.

“Guilt beyond reasonable doubt hasn’t happened yet, because there’s another side to what happened,” Bettman said. “He’s not going to shoot somebody in a parking lot, nobody would, depraved mind or otherwise.” He discredited the claim that Savannah didn’t want to be with Hill, though the jury had heard a long text she had sent her mother a few weeks before the shooting, telling her she was getting out of the relationship and the abuse she was enduring.

“Why do we know it’s an accident? Because he testified, he really wanted to sell the gun, so he unloaded it,” Bettman argued to the jury in one of his far weaker points: to ask the jury to believe Hill at that point was almost to insult the jury’s intelligence. Bettman’s closing argument jumbled from plaint to plaint with refrain after refrain about “reasonable doubt,” at one point telling the jury that doubt would linger regardless of the verdict: “Everybody is going to leave here with a really funny feeling no matter what.”

“Everyone is human, everyone makes mistakes, Brenan made a mistake, a terrible mistake, he did things wrong that he wasn’t supposed to do,” Bettman said, before unabashedly borrowing Hill’s reasoning (“Bitch if I wanted to kill you I’ll just kill you”) but in less caustic terms. He said if Hill wanted to kill her, he had 12 bullets to do it with: “If he was deranged, if he was going crazy, pop pop pop pop pop he could have done it 12 times,” he said, his hand mimicking a gun. “That would be crazy. One time and rushing to the hospital isn’t crazy.”

Perhaps one time and hopping out of the car to bury the gun in one of the busiest shopping areas of Palm Coast, then calling his mother to lie, then sending cops on wild goose chases and lying for the next several hours in all sorts of variations as his girlfriend barely clung to life was not exactly normal.

But that, too, still doesn’t rule out reasonable doubt.

“Not guilty is the only reasonable verdict in this case,” Bettman told the jury. “The only one, because the state failed to prove it. They’re asking you to speculate or asking you to help. It’s just didn’t happen. No matter what your verdict is, you’re going to feel bad about it. You’re going to feel bad because he wasn’t prudent, and you’re also going to feel bad because he may be a person that you disapprove of. But there’s a lot of people that don’t commit crimes of murder, just because you disapprove of the way they handle themselves.”

The case had astonishing similarities with that of Keith Johansen, https://flaglerlive.com/johansen-trial-day-3/#gsc.tab=0“>tried and convicted in the same courtroom two years ago in the murder of his wife, Brandi Ruth Celenza, 25, by gun in their home in Palm Coast. Johansen had immediately lied about the shooting, starting with lies to the 911 operator, to paramedics and to his own parents, first saying Celenza had shot herself, then changing his story to say he’d shot her in self-defense.

As in the Hill case, there was no direct evidence of the shooting itself. But as in the Hill case, Johansen had immediately started covering up the scene of the shooting.

And as in the Hill case, numerous interior videos had captured the sort of relationship Johansen had with Clenza: he was abusive, demeaning, threatening and a narcissist who, like Hill, had a handgun that he flashed. Like Hill, he had threatened to kill Celenza in the days leading up to the murder, and like Hill, he claimed to love her and do everything he could for her. Celenza had a young child in the house. Hill and Gonzalez had no children. Like Hill, Johansen took the stand in his own defense, and said he was no longer lying.

Johansen was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

![]()

Me says

It’s never the one guilty of the crime, it was the guns fault it slipped while he was cleaning it. Nice try buddy and glad the jury didn’t buy it.

C’mon man says

Jury got that right. Good job to them for seeing through the defense BS and getting this family some closure