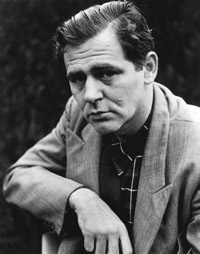

James Agee was born in 1909 in Knoxville, Tenn. He was schooled at Phillips Exeter Academy and Harvard, and worked at Time, Fortune and The Nation. He is best known for Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the book he wrote, with photographs by Walker Evans, after a 1936 assignment from Forbes documenting the lives of sharecroppers in what Larry McMurtry called “the gloomy South.” His enormous talent never translated much beyond that book.

Agee died when he was only 45, undone “by alcohol, nicotine, insomnia, overwork, misused sex, and searing guilt, and –above all, we can guess–by his anger and despair at finding that with all his wild talent he had never been able to write the whole of the universe down on the head of a pin.” As a film critic for The Nation, he wrote one of his most enduring essays in October 1943, on the wide gulf between what Americans at home pretended to know about war, and what people in most other nations were suffering through war first hand. Hollywood was attempting to bridge some of the gap with movies (famously, or infamously, counting Ronald Reagan among its PR flackers: held back from active service during World War II, Reagan invaded movie lots instead).

Agee was writing about the wars in Europe and the Pacific, but his words could just as easily refer to Iraq and Afghanistan, whose veterans have complained, bitterly, of a similar disconnect, underscored by the Bush administration’s decision some years ago to forbid the press from being present when coffins returned from the war theaters. “The unintended consequence is a further detachment of the populace not seeing their fallen service member come home,” Maj. Steve Beck says in Jim Scheeler’s Final Salute, one of the rare books that go beyond the chest-thumping over veterans to explore the consequences of soldiers’ deaths at home, on those they’ve been made to leave behind. “I think that in many ways the people in this country are detached from the war—financially detached, emotionally detached. With the exception of their political stance—that’s how they’re attached—is what party they belong to. That young lance corporal, his politics don’t mean anything. He’s fighting for the guy next to him and for us.” Beck went on: “We consider these men and women who go forward to fight for us the lifeblood of our country national treasures. When we lose something, we lose something important, and we should feel it. If you don’t feel this loss in some way, I’m not so sure you’re an American, frankly. When I hand that flag to them and say ‘On behalf of a grateful nation,’ it’s supposed to mean something. If [the public] is emotionally detached in some way, I don’t know how grateful they really are. Politics aside, is the nation grateful for that loss? If they’re emotionally detached, it’s almost–It’s almost criminal.”

And it’s nothing new. The emotions and doubts are accentuated on Veterans and Memorial Day, when the nation enacts superficial honors and manufactured sorrows that exploit the moment more than they understand them–as war movies do. The detachment is similar, and was analyzed by James Agee in 1943, when he predicted that “our great majority will emerge from the war almost as if it had never taken place,” just as the great majority of Americans have emerged from Iraq and Afghanistan still not knowing where to place either of these two countries, nor knowing how many people have been killed there (Americans or not), or what was achieved, if anything, through the waste. The two wars were not mentioned during the presidential campaigns, except as distant footnotes, like their dead. Here’s Agee’s “So Proudly We Fail.”

![]()

Since it is beyond our power to involve ourselves as deeply in experience as the people of Russia, England, China, Germany, Japan, we have to make up the difference as well as we can at second hand. Granting that knowledge at second hand, taken at a comfortable distance, is of itself choked with new and terrible liabilities, I believe nevertheless that much could be done to combat and reduce those liabilities, and that second-hand knowledge is at least less dangerous than no knowledge at all. And I think it is obvious that in imparting it, moving pictures could be matchlessly useful. How we

might use them, and how gruesomely we have failed to, I lack room to say; but a good bit is suggested by a few films I want to speak of now.

Even the Army Orientation films, through no fault intrinsic to them, carry their load of poison, of failure. You can hear from every sort of soldier from the simplest to the most intricate what a valuable job they are doing. But because they are doing it only for service men they serve inadvertently to widen the abyss between fighters and the civilians who need just as urgently to see them. Civilians, however, get very little chance to learn anything from moving pictures. We are not presumed to be brave enough. And the tragic thing is that after a couple of decades of Hollywood and radio, we are used to accepting such deprivations and insults quite docilely; often, indeed, we resent anyone who has the daring to try to treat us as if we were human beings.

Just now it is a fought question whether numbers four and five of the Orientation Series, “The Battle of Britain” and “The Battle of Russia,” will get public distribution. Whether they do depends on what is laughingly called the Office of War Information and on what is uproariously called the War Activities Committee. The OWI’s poor little pictures, blue-born with timidity from the start, have finally been sabotaged out of existence; and judging by the performance to date of the WAC, it is not very likely that we shall see these films. And if we do see them, it is more than likely that we shall see them with roast albatrosses like “The Keeper of the Flame” hung around their necks.

I can only urge you to write your Congressman, if he can read. For these films are responsible, irreplaceable pieces of teaching. “Britain,” one hour’s calculated hammering of the eye and ear, can tell you more about that battle than you are ever likely otherwise to suspect, short of having been there. “Russia,” though it is a lucid piece of exposition, is cut neither for fact nor for political needlepoint but purely, resourcefully, and with immensely powerful effect, for emotion. It is by no means an ultimate handling of its material, but it is better than the Russian records from which it was drawn, and, next to the tearful magnificence of “The Birth of a Nation” is, I believe, the best and most important war film ever assembled in this country.

Beside it Samuel Goldwvn’s “The North Star” is somethingi to be seen more in sorrow than in anger and more in the attitude of the diagnostician than in any emotion at all. It represents to perfection some crucially symptomatic characteristics of Hollywood and of the American people in so far as Hollywood reflects, or is accepted by, the people. Hollywood’s noble, exciting, all but unprecedented intention here is to show the conduct of the inhabitants of a Russian border village during the first days of their war; to show real people involved in realities, encumbered by a minimum of star-spotlighting or story. The carrying out of that intention implies in every detail the hopeless mistrust in which Hollywood holds its public. To call this “commercial” and to talk about lack of intelligence and taste is, I think, wide of the main mark. The attitude is more nearly that of the fatally misguided parent toward the already all but fatally spoiled child. The result is one long orgy of meeching, sugaring, propitiatio which, as a matter of fact, enlists, develops, and infallibly corrupts a good deal of intelligence, taste, courage, and disintestedness. I am sorry not to talk at length and in detail about this film.

I can only urge you to watch what happens in it: how every attempt to use a reality brings the romantic juice and the annihilation of any possible reality pouring from every gland. In its basic design Lillian Hellman’s script could have become a fine picture: but the characters are stock, their lines are tinny-literary, their appearance and that of their village is scrubbed behind the ears and “beautified”; the camera work is nearly all glossy and overcomposed; the proudly complicated action sequences are stale from overtraining; even the best of Aaron Copland’s score has no business ornamenting a film drowned in ornament: every resourcefulness appropriate to some kinds of screen romance, in short, is used to make palatable what is by no remote stretch of the mind romantic. I think the picture represents the utmost Hollywood can do, within its present decaying tradition, with a major theme. I am afraid the general public will swallow it whole. I insist, however, that that public must and can be trusted and reached with a kind of honesty difficult, in so mental-hospital a situation, to contrive; impossible, perhaps, among the complicated pressures and self-defensive virtuosities of the great studios.

The thing that so impresses me about the non-fiction films which keep coming over from England is the abounding evidence of just such a universal adulthood, intelligence, and trust as we lack. I lack space to mention them in detail (the new titles are “I Was a Fireman,” “Before the Raid,” and, even better, “ABCA” and the bleak, beautiful, and heartrending “Psychiatry in Action”), but I urge you to see every one that comes your way. They are free, as not even our Orientation films are entirely, of salesmanship; they are utterly innocent of our rampant disease of masked contempt and propitiation. It comes about simply enough: everyone, on and off screen and in the audience, clearly trusts and respects himself and others.

There is a lot of talk here about the need for “escape” pictures. To those who want to spend a few minutes in a decently ventilated and healthful world, where, if only for the duration, human beings are worthy of themselves and of each other, I recommend these British films almost with reverence as the finest “escapes” available.

![]()

First published in The Nation, October 30, 1943, and re-published in Reporting World War II, Part One, 1938-1944, the Library of America, pp. 658-61, and in Film Writing and Selected Journalism, the Library of America, pp. 71-74. The piece originally appeared in FlaglerLive in 2012.

Jim R. says

Agee was also a poet, and did the screenplay for Moby Dick. his prologue to his book, A death in the family

is one beautiful, poetic and unforgettable paragraph. His anger and rage about the suffering of the poor and the inequities in 1930s America would probably be even more intense were he still alive.

To read his work, is to admire him not just as a writer but a great human being.

Pogo says

@Foppish pedantry

For whom – the same slobs who’ve elected the bush family, cheney (and his ex poodle waltz) scott, rubio, desantis, and wild bone spurs trump? Really?

William Moya says

Yesterday on Twitter someone published a photo of a woman lying on the grave, of I assume to be her husband, next to her, she had her baby, she was face down, but i’m sure there were tears. I choked up. It was as powerful as a series on the Nazi invasion of Russia I saw recently, where 24 million died during the war.

To those who choose attribute War with a romantic flavor I say, we go to war for domestic politics, we go to war to satisfy our capitalistic impulses, and we go to war to submiss our enemies as well as our allies.

Layla says

You know, I can’t think of a more inappropriate subject for Memorial Day than this. Without the efforts of these soldiers, millions more would now be speaking German and living in tyranny. You cannot write about American history without understanding it. And it is clear that is the case here. What a bunch of drivel.

oldtimer says

Some personal thoughts on how we view our vets. In 1973 the Vietnam war was winding down I had just completed navy boot camp,I was in Chicago-Ohare airport in my dress blues,hadn’t even left the country yet. While waiting for my flight I was called a Fascist, a Baby killer and worse.When I got to Norfolk signs said “Sailors and dogs keep off the lawn”.In San Francisco we were asked not to wear our uniforms into the “fine” dining areas because it would upset the patrons! Fast foward to now,when I wear my navy cap people thank me for my service,Lowes gives me 10% discount.I’m the same man now as then so what changed?The thing I wonder about is how many people my age that now shake my hand spit at me then?

Makes you wonder