Perhaps the Flagler County administration could teach Bunnell’s city government a thing or two about keeping their business open to the public.

Earlier today Enterprise Flagler, the public-private economic development partnership, took one of its quarterly luncheons on the road. The agency held it at Daytona State College’s Advanced Technology College, which the Flagler County school district partly funds and where students from Flagler and Volusia district schools can enroll while they’re still in high school, and earn college credit.

Click On:

- Beyond Sunshine: Maneuvers Over Carver Gym Reopen Wounds Flagler Claims to be Mending

- Bunnell’s Crain-Brady Leads Half-Secretive Meeting of 4 Gov’t Agencies on Carver Gym

- How Race and Deception Are Cleaving the Fate of Bunnell’s Carver Gym

Enterprise Flagler meetings are subject to the government-in-the-sunshine law and are publicly announced, enabling the public to take part. Whether it was a public meeting or not, the Flagler County Commission has an administrative policy that whenever a gathering takes place where two or more commissioners might be in attendance, whether socially or officially, the county publicly notices the meeting—even when the county isn’t calling that meeting.

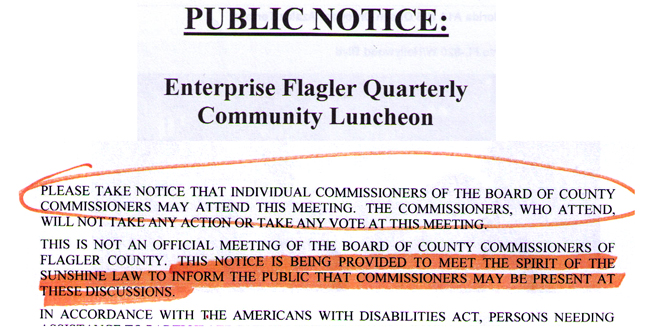

The county’s public notice for today’s Enterprise Flagler luncheon, for example, which was posted—as are all county notices—in the lobby of the government services building in Bunnell as well as at the county courthouse, included these words, in capital letters: “Please take notice that individual commissioners of the Board of County Commissioners may attend this meeting,” though neither to take action or to vote. “This notice is being provided to meet the spirit of the sunshine law to inform the public that commissioners may be present at these discussions.”

There is no clearer statement of county policy to meet not only the letter of the law, but its spirit, which is equally important when it comes to projecting openness in fact and appearance: government gatherings, or merely government-related gatherings, even social gatherings where nothing more than discussions, tours, fact-finding or food-sampling is taking place, are meant to be open and transparent because they exist for the public’s sake. No government is a club unto its own (though many governments act that way when the public isn’t looking.)

The same county notice appears in larger or finer print at the bottom of recent notices for all sorts of meetings, including one for an affordable housing advisory committee, an obscure committee hardly anyone’s heard about regarding the design of an eventual highway interchange at Matanzas Woods, the airport authority, and several other groups.

No such notice was produced for the meeting last week on Carver Gym, involving elected officials and staff members from Bunnell, the county, the school board and the county housing authority. That meeting was called by Bunnell City Commissioner Jenny Crain-Brady, who said it didn’t need to be publicly noticed. Brady wanted to hold an invitation-only meeting, and did so, expressly inviting people who generally agreed with her vision for the embattled gym and excluding those who have offered different perspectives. According to Crain-Brady, there was general agreement among those gathered that the gym should not close, and that Crain-Brady’s proposal for Bunnell to buy the building from the county should be followed through.

Two county commissioners—George Hanns and Barbara Revels—were at the meeting, though Revels sat in the audience while Hanns was at the discussion table, and the two never engaged in discussion. Neither was aware that the meeting had not been publicly noticed—until County Administrator Craig Coffey tried to shoo Revels away. She did not go, having received an invitation either from Crain-Brady or through the county (the county couldn’t find an invitation to Revels, and Revels couldn’t recall where she’d received the invitation). Had the county been aware that both commissioners would attend, County Spokesman Carl Laundrie said, the routine public notice would have been issued ahead of time.

But those notices are issued whether or not two or more commissioners are certain to be at such gatherings. The fact that it wasn’t in the Carver Gym meeting’s case ensured that the meeting got no public notice whatsoever. That’s how Crain-Brady wanted it, and how Bunnell City Manager Armando Martinez organized it (he said no one would have been turned away from the old Bunnell City Hall, where the meeting was held, had members of the public shown up there), and how Coffey went along with it.

Unlike a meeting on a far-off highway overpass design few people are engaged in, or other variably obscure meetings of local authorities and committees, the Carver Gym meeting did not involve a small or obscure matter, but a public one that’s alternately dividing and uniting different segments of government and neighborhood communities. All those involved, especially at the meeting Crain-Brady called (beginning with Crain-Brady herself) knew that. If there’s been a recent meeting that warranted the county’s notice “to meet the spirit of the sunshine law,” that one qualified.

“When you have any sort of meeting that’s going to have a huge sort of impact on the community and it’s going to involve decisions,” Jim Rhea, director of the Tallahassee-based First Amendment Foundation, said, without sunshine, “it’s going to raise eyebrows.” It’s not just the decision-making at stake, but the discussion that may eventually lead to decisions that should be aired, he said.

Coincidentally, Laundrie said he was considering inviting the First Amendment Foundation’s president, Barbara Petersen, for a seminar to local government agencies, presumably — or hopefully — including Bunnell.

Leave a Reply