To hear Rymfire Elementary Principal Paula St. Francis tell it, when the superintendent asked her to 9choose a flagship program for her school, she turned over the question to her student council—fourth, fifth and sixth grade students—to think about “what we do well here.”

Flagship programs are the two-year-old district-wide initiatives that seek to bridge learning and the workplace from elementary schools and up. Superintendent Jacob Oliva has asked each Flagler school to develop a curriculum focused on related professions. Belle Terre Elementary picked robotics. Bunnell and Wadsworth elementaries are into agri-science. Matanzas High School picked financial literacy, with an actual bank branch based at the school and employing high school students.

Rymfire students picked medical sciences, health and fitness. “What do you want a medical lab to look like, what do you want to learn in a medical lab, what kind of things would you like to see after school that are connected to having a medical school program,” St. Francis asked her students. The school teamed up with Florida Hospital Flagler, which stocked the medical lab with some $7,000-worth of equipment (including a hospital bed) and the Flagler County Education Foundation—the district’s non-profit arm, which provided $10,000 (half of it from the Florida Consortium of Education Foundation matching grants program).

Tuesday evening, Rymfire’s students showcased the results: a health class, a technology class, a research lab, the medical lab, and afterschool clubs that focus on nutrition and science, gardening math in sports and science, among others.

With the school’s steel-drum band jazzing up the campus, several dozen guests—including Oliva, Florida Hospital Flagler CEO Ken Mattison and Daytona State College’s Kent Ryan—got a chance to see each area in action. In Donelle Evensen’s research lab, two teams of three students each were working on figuring out the math and science of nutrition and logistics by calculating what type of food could most efficiently be delivered to restaurants, and in what form. It so happened that the food they were referring to was insects, and they had to figure out which of the five types—locust, mealworm, cricket, caterpillar, grasshopper—was best suited for restaurant food. (It must be one of those nouvelle cuisine trends.)

The results weren’t entirely clear: visitors, split in three or four groups, were efficiently ushered from one area to another by members of the student council such as fourth-graders Bryce Willis and Dawson Cope, the latter a future physician who used his stopwatch to ensure that no one lingered.

In Denise Tyler’s technology class, 6th grader Noelle Gonzalez showcased the brochure she’d produced on migraines. She knows her subject. She didn’t just study it. She is a frequent migraine sufferer. “Keep the lights off, low noises can help,” she says. And in school? “I usually go to the nurse’s office and lay down in there. It usually helps.” (See her actual brochure below.) Nearby, second grader Meily Suarez developed her own presentation on safety rules in school.

“The kids come to me for two weeks at a time, and during those two weeks each grade will do a specific project according to the state standards for technology,” says teacher Denise Tyler. “We’re trying to incorporate the health, the science and the technology into their writing. That’s the flagship.”

Willis and Cope brandish their stopwatches again. The next room is all about health: in one place, a student is holding an iPad and doing what at first looks a bit odd: he’s hopping, jumping, seemingly running in place, the entire time his eyes glued on the screen. It’s Gavin Dubena, a fifth grader. Nothing odd about it. He explains: he’s using an app called NFL Play 60 to enact various exercises paired with a circuit on screen where his avatar is running a course, jumping, taking water breaks, and so on.

Not far off, a student had arrayed one of the most frightening displays of the evening, the one that caught School Board member Trevor Tucker’s attention. The student had placed soda bottles next to plastic cups, and filled the cups with the actual sugar equivalent in each of the bottles: 28 grams in an 8-oz bottle of Coke, and an astounding 77 grams in a 12-oz bottle of that poison and ruin of American health care commonly known as Mountain Dew. The cup was almost half-full with sugar. “If you see that, it’s actually shocking that you can cram that much sugar into the bottle,” Tucker said.

(© FlaglerLive)

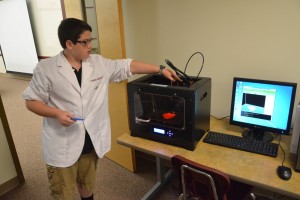

Then there’s the medical lab: the centerpiece of the evening. It’s a big room with several stations set up around its rim, alongside walls graphed up in the look of a heart monitor and beneath a row of portraits of history’s most famous medicine folks, from Hippocrates to Marie Curie. Students are hard at work: some doing tests on peripheral vision, some exploring the heart through “4-D augmented technology,” some doing comparative anatomy between human frames and those of a lemur, a rabbit and a couple of other animals, and yet another couple of students figuring out human endurance by measuring muscle mass and doing push-ups. In a smaller room nearby: a 3-D printer, though Janie Ruddy, the science and math academic coach at Rymfire, who’s written the lesson plans for the medical lab, says the faculty is still trying to figure that one out.

At every step, the students, who seem never to miss a beat between the absorption in their work and their ability to explain their task to whoever asks, speak with ease and command about their station, their seemingly novel wares as second nature to them as the pencil—or the old Kaypro keyboard—might have been to visitors a generation or two older than them.

That’s what impressed Florida Hospital Flagler CEO Ken Mattison, who summed up his experience after touring the various stations Tuesday evening. “I was very impressed with the level of engagement that I saw in the students that I interacted with at all of the stations,” Mattison said. “What was amazing to me is that they weren’t just reciting something that they had learned. They had actually learned it and they were speaking from their heart. That was just phenomenal to me. I can’t think of a better reward from my perspective than seeing those kids excited about science and about health care. I also believe that they’re learning good health habits as part of it, and if we’re not impacting the health of our community by teaching better habits at a young age, I think we’ve hit on something that’s going to have an impact on improving the health status of the community.”

Mattison added: “Members of our medical staff have gotten engaged in helping our community and I wanted to highlight the work that Dr. Bower has done. Dr. Steven Bower as a surgeon has actually gotten involved here and trying to be a good role model and a mentor to these kids. It’s just truly amazing when I see people like Dr. Bower and other physicians on our medical staff who are willing to give back, and to me that’s just an extraordinary thing. I love being engaged with them.”

(© FlaglerLive)

“How gratifying it will be if we are able to influence the students here to some day pursue a career in health care and then come back in their own community to practice,” said Robert Davis, the hospital’s chief nursing officer, whose involvement in the Rymfire flagship was also key. At the origin of it all Florida Hospital Flagler Foundation Director John Subers connected Davis with St. Francis, Davis toured the school figured out what the school needed, then provided it. “The next phase of this partnership is to open a speakers’ bureau,” Davis said. It would work both ways: students would go to the hospital for tours, and to hear health care professionals speak there of their various roles, and those professionals would also visit the school to do likewise.

Oliva, the ubiquitous superintendent, stayed in the background Tuesday evening, letting others claim the limelight. But his satisfaction was palpable. “This is another great example of how we can bring to local economic folks targeted industries and develop programs in our schools around them,” Oliva said. “The medical field is something that’s going to continue to expand. Florida Hospital Flagler is one of the top employers in our community and they’ve been a great partner in helping us get this curriculum and room developed.”

The flagship program, a signature initiative of Oliva’s young tenure, goes beyond the flash, of course: “One of the goals we have is for our students to see the relevancy on why they’re learning and how it relates to the world around them,” the superintendent said. “So we’re not telling the students they need to choose a career in the medical field in third grade, but if they can understand how the different sciences and math that they’re learning in their core curriculum relates to the world around them, that can motivate them to want to learn more.”

![]()

Noelle Gonzalez’s Migraine Project

Leave a Reply