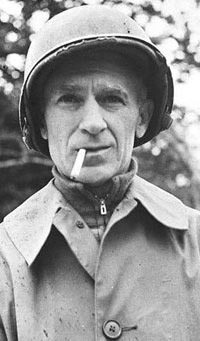

“Ernie Pyle,” the New York Times reported on April 19, 1945, “died today on Ie Island, just west of Okinawa, like so many of the doughboys he had written about. The nationally known war correspondent was killed instantly by Japanese machine-gun fire. The slight, graying newspaper man, chronicler of the average American soldier’s daily round, in and out of foxholes in many war theatres, had gone forward early this morning to observe the advance of a well-known division of the Twenty-fourth Army Corps.” The bullet entered his left temple, just under the helmet. And just like that, one of the great war reporters and columnists of the 20th century was dead. Ernie Pyle’s columns during World War II were read from the White House to some 14 million homes across the United States, like personal letters from the front. His style was stark and familiar: Hemingway without the presumptions. He had the novelist’s eye for observation, he knew what patriots wanted to hear, he also knew how to use his popularity to convey a compassion for men in uniform that didn’t stop with Americans only. His columns from Omaha Beach in 1944 are among his best, winning him the Pulitzer Prize that year.

The column below in particular manages to convey “this shoreline museum of carnage”–the loss of human life on Omaha Beach was the highest of the five landing zones on June 6–only to justify it with the startling line: “And yet we could afford it.” It’s a strange transition for what comes next, resigned and hopeful for what floats in the seat beyond Omaha Beach: “We could afford it because we were on, we had our toehold, and behind us there were such enormous replacements for this wreckage on the beach that you could hardly conceive of their sum total. Men and equipment were flowing from England in such a gigantic stream that it made the waste on the beachhead seem like nothing at all, really nothing at all.” It was early June 1944, but the outcome was already inevitable, especially in the eyes of captured Nazi soldiers, whose realization Pyle conveys at the end of the column: “The prisoners too were looking out to sea—the same bit of sea that for months and years had been so safely empty before their gaze. Now they stood staring almost as if in a trance.” They could see that it was over but for the carnage ahead, useless even as it was made necessary by Hitler’s and Hirohito’s mass-murdering obstinacy.

Here’s Pyle’s column from Omaha Beach on this anniversary of the D-Day invasion.

![]()

NORMANDY BEACHHEAD, D Day Plus Two—(by wireless, delayed)—I took a walk along the historic coast of Normandy in the country of Prance. It was a lovely day for strolling along the seashore. Men were sleeping on the sand, some of them sleeping forever. Men were floating in the water, but they didn’t know they were in the water, for they were dead.

The water was full of squishy little jellyfish about the size of your hand. Millions of them. In the center each of them had a green design exactly like a four-leaf clover. The good-luck emblem. Sure. Hell yes.

For a mile out from the beach there were scores of tanks and trucks and boats that you could no longer see, for they were at the bottom of the water—swamped by overloading, or hit by shells, or sunk by mines. Most of their crews were lost. You could see trucks tipped half over and swamped. You could see partly sunken barges, and the angled-up corners of jeeps, and small landing craft half submerged. And at low tide you could still see those vicious six-pronged iron snares that helped snag and wreck them.

On the beach itself, high and dry, were all kinds of wrecked vehicles. There were tanks that had only just made the beach before being knocked out. There were jeeps that had burned to a dull gray. There were big derricks on caterpillar treads that didn’t quite make it. There were half-tracks carrying office equipment that had been made into a shambles by a single shell hit, their interiors still holding their useless equipage of smashed typewriters, telephones, office files.

There were LCT’s turned completely upside down, and lying on their backs, and how they got that way I don’t know. There were boats stacked on top of each other, their sides caved in, their suspension doors knocked off. In this shoreline museum of carnage there were abandoned rolls of barbed wire and smashed bulldozers and big stacks of thrown-away lifebelts and piles of shells still waiting to be moved.

In the water floated empty life rafts and soldiers’ packs and ration boxes, and mysterious oranges. On the beach lay snarled rolls of telephone wire and big rolls of steel matting and stacks of broken, rusting rifles.

On the beach lay, expended, sufficient men and mechanism for a small war. They were gone forever now. And yet we could afford it.

We could afford it because we were on, we had our toehold, and behind us there were such enormous replacements for this wreckage on the beach that you could hardly conceive of their sum total. Men and equipment were flowing from England in such a gigantic stream that it made the waste on the beachhead seem like nothing at all, really nothing at all.

A few hundred yards back on the beach is a high bluff. Up there we had a tent hospital, and a barbed-wire enclosure for prisoners of war. From up there you could see far up and down the beach, in a spectacular crow’s-nest view, and far out to sea.

And standing out there on the water beyond all this wreckage was the greatest armada man has ever seen. You simply could not believe the gigantic collection of ships that lay out there waiting to unload.

Looking from the bluff, it lay thick and clear to the far horizon of the sea and on beyond, and it spread out to the sides and was miles wide. Its utter enormity would move the hardest man.

As I stood up there I noticed a group of freshly taken German prisoners standing nearby. They had not vet been put in the prison cage. They were just standing there, a couple of doughboys leisurely guarding them with Tommy guns.

The prisoners too were looking out to sea—the same bit of sea that for months and years had been so safely empty before their gaze. Now they stood staring almost as if in a trance.

They didn’t say a word to each other. They didn’t need to. The expression on their faces was something forever unforgettable. In it was the final horrified acceptance of their doom.

If only all Germany could have had the rich experience of standing on the bluff and looking out across the water and seeing what their compatriots saw.

Scripps-Howard wire copy, June 16, 1944

Laura says

This man’s reality, and your willingness to assign his words to these pages

will fit all too neatly into our study of this era.

I will read it aloud to my children, without flinching.

{{* *}}