Bob Woodward is a celebrity reporter perceived as the ultimate insider, but for the wrong reasons. He does not reveal anything. He is not analytical or critical, a skeptic of any sort or a questioner of any depth, and context is a concept as foreign to him as foreign policy. He only conveys an image the “principals” on the inside, as Woodward loves to call them, want to reveal.

Whether his book is about The Commanders of the first Gulf War, The Secret Wars of the CIA, The Agenda of the Clinton White House or The Choice in the 1996 presidential election, possibly the dullest election of the century, Woodward’s loyal court-chronicling method explains why he has ready access to all those secret memos, legal pads, National Security Council minutes and CIA briefing papers that make up the bulk of his bulky books, and why most principals in the end choose to speak with him as opposed to an actual reporter. He is the print equivalent of a White House photographer, transcribing official moods and postures usually in a light most favorable to those who do speak with him, and most unfavorable to those who don’t. The books zoom up the bestseller charts for the same reason voyeuristic books about celebrities’ tics and tiffs do: Inquiring minds want to know, and a Woodward book is as close as they’ll get to a reality show from the White House situation room.

Whether his book is about The Commanders of the first Gulf War, The Secret Wars of the CIA, The Agenda of the Clinton White House or The Choice in the 1996 presidential election, possibly the dullest election of the century, Woodward’s loyal court-chronicling method explains why he has ready access to all those secret memos, legal pads, National Security Council minutes and CIA briefing papers that make up the bulk of his bulky books, and why most principals in the end choose to speak with him as opposed to an actual reporter. He is the print equivalent of a White House photographer, transcribing official moods and postures usually in a light most favorable to those who do speak with him, and most unfavorable to those who don’t. The books zoom up the bestseller charts for the same reason voyeuristic books about celebrities’ tics and tiffs do: Inquiring minds want to know, and a Woodward book is as close as they’ll get to a reality show from the White House situation room.

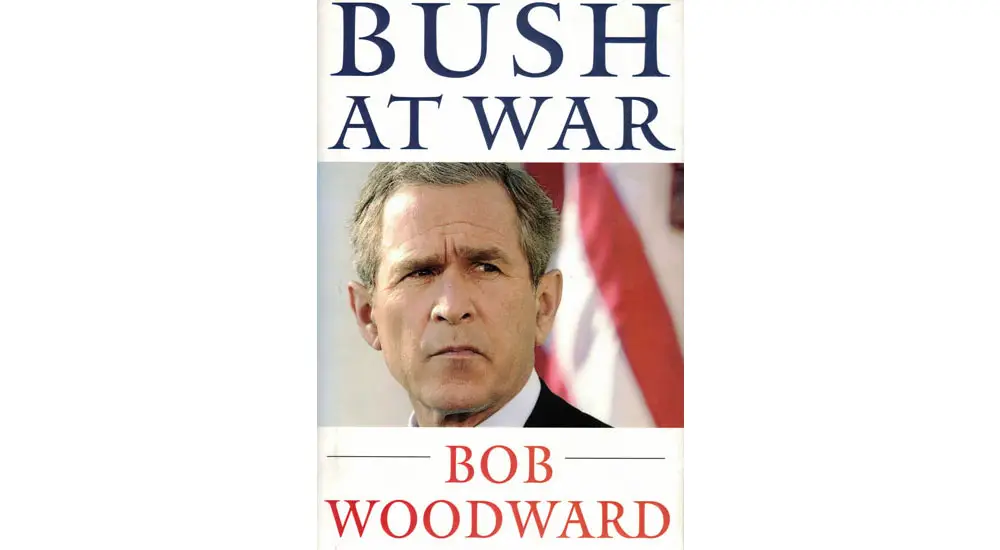

Bush at War, Woodward’s latest, is a competent, plodding chronicle of the Bush cabinet’s 100 days from Sept. 11 to the fall of the Taliban in Afghanistan. A few scoops about the president’s sleeping problems or the secretary of defense’s catfights with the secretary of state are sprinkled along the way to keep the story moving, like sex scenes in a Danielle Steel novel, but the book is remarkably devoid of anything new or surprising. No average consumer of 22 minutes of daily news would be surprised to know that the president is impulsive, intolerant of doubt or second-guessing, that the secretary of defense is tyrannical, that the vice president can’t wait for another war, that the secretary of state’s love of coalitions makes him the odd man out in an administration of shoot-first unilateralists, or that the CIA buys off enemies with trunks of taxpayer cash. (It is surprising that dozens of Taliban chiefs’ defections can be bought off at $50,000 per while lesser foot soldiers have ended up in shackles at Guantanamo Bay.)

If that’s all it was, Bush at War wouldn’t warrant more than the usual reviews and chat-show buzz every Woodward book generates. But even by Woodward’s standards, this is much less a journalist’s book than a White House manifesto, a managed reconstruction of recent events not for the sake of telling the story of those events, but as a projection of events to come. What B-52s do to soften up enemy ground ahead of a military invasion, Bush At War is doing to soften up Bush’s coming war on Iraq and possibly more.

The president says as much a few pages from the end of the book, when Woodward, as if oblivious to having been supremely managed all along, proudly reveals the substance of his talk with Bush at the president’s Texas ranch: “His blueprint or model for decision making in any war against Iraq, he told me, could be found in the story I was attempting to tell – the first months of the war in Afghanistan and the largely invisible CIA covert war against terrorism worldwide. ‘You have the story,’ he said. Look hard at what you’ve got, he seemed to be saying. It was all there if it was pieced together – what he had learned, how he had settled into the presidency, his focus on large goals, how he made decisions, why he provoked his war cabinet and pressured people for action.”

Bush at War is above all a Portrait of the President As a Grown-Up, but a grown-up who seems to have no qualms about remaking the world in line with his messianic visions. “I’m here for a reason, and this is going to be how we’re going to be judged,” Bush said shortly after Sept. 11, explaining why the attacks would prove to be such a huge “opportunity.” “There’s nothing bigger than to achieve world peace,” he would say again and again – a Miss America-like idealist, but as Commander in Chief of the most lethal army in history.

The book’s implications are frightening not just because they raise the very questions that aren’t being asked, but because the “inside” information coincides so accurately with what’s been perceived on the outside all along. The attacks of Sept. 11 were a pretext, and so is the so-called war on terrorism. The aim is much larger. The question is not whether the Bush cabinet will take on that aim, or whether it can convince Americans to endorse it. The question is how, and when.

Part of the answer is a book like Bush at War, which achieves both the “how” and implies the “when.” It invites that mythical average American to have a seat at those super-secret NSC meetings, to watch the commander in chief in action and to sense his zeal for “world peace.” It turns the reader into a partner in the grand design, an insider who, like most members of the Bush cabinet, don’t question the president’s aims, but tell him what he wants to hear. The president, Woodward writes, is “casting his mission and that of the country in the grand vision of God’s master plan.” As such, what he wants to hear from his cabinet is how to turn the Battle Hymn of the Republic into kinetic energy for the Pentagon. What he wants to hear from Americans is “You da man.”

The book’s title summarizes the 352-page manifesto without meaning to be so reductively simple minded. And yet the meaning of the Bush White House is exactly that simple, that mindless. It is about Bush’s war – not the nation’s, not the world’s. To a president who thinks he’s personally doing God’s work and the world a favor, a doctrine needs be no more complicated than “you’re either with us or against us,” with one correction. He actually means, “You’re either with me or against me.” Richard Nixon would be proud.

![]()

Pierre Tristam is the editor of FlaglerLive. Reach him by email here. A different version of this review appeared in the News-Journal on Dec. 3, 2002.

Leave a Reply