It was a painful day for Zuheili Rosado’s family. But it’s been a painful six and a half years for the family since Joseph Bova murdered her, a single mother of six, as she worked the late shift at the Mobil convenience store on Palm Coast’s State Road 100 in February 2013.

Today the family sat in the same room as Bova for the first time–for the only time–since the murder, when Bova shot Rosado three times at point-blank range.

The family–Rosado’s now-grown children, her mother, an interpreter–sat in the same room where images and videos of the shooting again and again flashed on three oversized television screens, from eight different angles.

The video had no sound. For long stretches, each second ticking as if in slow motion on the surveillance time stamp, there were no sounds in the courtroom, either, except when a prosecutor would ask a witness to confirm what everyone was seeing on the screen. Then back to silence, to Bova’s appearances and reappearances, his lifting that gun and shooting it and walking out.

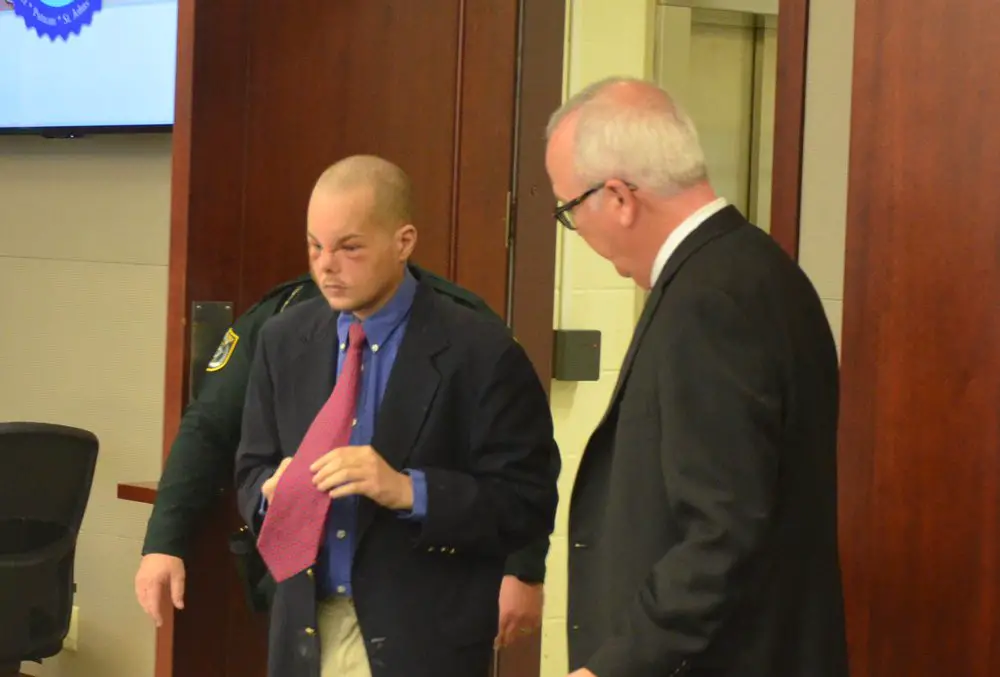

Bova who today sat between his two defense attorneys and unflinchingly stared at the screen right next to him, no less seemingly mesmerized than the jury as he watched himself kill another human being. His eyes, puffed up from an inexplicable condition he’s attributed to allergies, hardly left the screen.

The video showed Rosado’s last moments: How she had been leaning against a counter, gazing out the window a little after 10 p.m. that night of February 13. How Bova, covering his face with a t-shirt he’d just slit for a pair of eyes so he could see through it, like a mask, hurried in, lifted his handgun as he walked toward Rosado, and shot her. She hadn’t had time to realize what was happening, let alone take cover. She was still leaning on the counter, and leaned still after he’d fired three times. As he rushed out she fell to the ground. She lifted her head once, twice, then died.

It was 13 seconds from the moment Bova walked in to the moment Rosado died.

Thirteen seconds that Assistant State Attorney Jason Lewis, whose dramatic sense often equals his withering prosecutorial skills, managed to memorialize at the start of his opening argument before a jury of eight women and six men this morning. He stood ramrod perpendicular to the jury to his right, his hands clasped as if in prayer, facing the family. He said: “Would you guys take the next 13 seconds with me.” It was hardly a question. No one could have expected it. The defense could have objected, but who can object to a memorialized moment of silence, however seemingly inappropriate in court: Lewis had so cleverly woven it into the essentials of his opening that he might as well have disarmed the defense before he’d made his first argument.

The defense is arguing insanity. In his opening later, Joshua Mosely told the jury that Bova was out of his mind that night, that it was the culmination of a grave episode of schizophrenia that had been building for months, that he’d been hearing voices, that the voices were telling him that Rosado was an evil person, that she could kill just by looking at you, and that it was his duty to kill her. “You have to kill her for the good of the American people.” That’s what the voices were telling Bova, Mosley said. “It’s a product of schizophrenia,” a condition he started suffering from after he was struck by a vehicle when he was on a bike when much younger, though the family was predisposed. “When it hits the Bova family, it hits hard,” Mosley said.

“Joseph Bova committed this homicide. There’s no dispute,” Mosley told the jury. But why, he asked. Because he was hearing voices. Because the voices told him to do it.

It’s not the strongest defense. But it’s all the defense has, all that Bova, who has gone through a series of attorneys in the past six years and tried again to fire his last two as recently as Monday, has left them with. He’s a strange man. No one is disputing that, either. But as much as the accused is normally innocent until proven guilty, and as much as that entire burden of proof rests on the prosecution, almost none of that applies in this case. In effect, the defense must prove insanity beyond a reasonable doubt.

And what a pre-trial hearing made clear on Monday, before jury selection–when Bova tried to represent himself–is that there’s serious doubt regarding the defense’s ability to get an expert witness to say that Bova fit the definition of insanity when he committed the murder.

The prosecution today showed a series of deliberate acts, a timeline plotting Bova’s steps, and reasoned, thought out behavior–from buying the handgun in Daytona Beach to the two trips to the convenience store, the preparation of the shirt, the use of a “secret” path behind the store (which, if Bova really was acting on behalf of the American people, would not have been necessary. The converse is that he knew he was committing a wrongful act, a central tenet of the state’s case against him, which is why he needed to hide his steps.) His fleeing Bunnell to Key West for four months, then Boca Raton for two, before his capture, is part of that thought-out timeline.

It was up to Flagler County Sheriff Detective Mark Moy to bring together that entire timeline today: he was the state’s chief witness just as he has been one of the rare constants in the case, Bova aside, investigating it from the very beginning. Today, he sat with the prosecution instead of in the hallway: the defense had waived the rule of sequestration in his regard. Moy, in short, filled in the evidentiary blanks that Lewis had laid out in his opening.

The arguments Lewis made and the evidence that followed–the videos, the pictures of a bloodied Rosado, the medical examiner’s description of the way one bullet had pierced her finger as she leaned on the counter, her head leaned against her hand, then traveled into her cheek and out from below an ear–was not that essential to the case: the defense is not disputing that Bova shot and killed Rosado. It’s not disputing the method, the time, the means, not even the cold-bloodedness of it. And the motive is not in question. The prosecution is not suggesting a motive.

But the prosecution today–Lewis is teamed up with Assistant State Attorney Mark Johnson–wanted to make two points: first, that Bova’s actions were deliberate, at every point planned, thought out, pre-meditated. He faces a first-degree, pre-meditated murder charge. To show pre-meditation, the prosecution sought to show from every possible angle where Bova was at every possible second before and after the shooting, when he approached the convenience store from the Coconut car wash business through a “secret,” dissimulated path (as Lewis described it), and took the same path back after the murder.

Those elements show forethought, as does his appearance at the convenience store earlier in the evening to withdraw $120 from the ATM before going home to the Palm Pointe apartments in Bunnell, where he cut out those eye slits in the shirt he’d use to cover his face, then returned to the store to shoot Rosado. Grainy nighttime surveillance video from Coconut and from red light cameras then in place established the timeline of Bova’s deliberate steps–what the prosecution seeks to show as deliberate steps, on foot and at the wheel of his vehicle.

The second point the prosecution wanted to make, especially with the replays of videos from various angles, verged on the gratuitous. The videos of Rosado’s shooting help its case, but are also intended to shock the jury and elicit a visceral reaction. And though all 14 members of the jury (who include two alternates) showed little emotion, they could not fail to see, or at least hear, the emotions from the Rosado family in the gallery: the tears, the sniffles, the way some of the family members covered their head to avoid seeing the horror on the screens all around–one of them did so with his shirt over his head–or covered themselves in the arms of a victim’s advocate, or the way some of them finally had to walk out.

A trial is about the evidence. It is also theater–some of it produced by the lawyers, like Lewis’s 13 seconds, some of it elicited by them through testimony or images played strategically at a certain frequency and intervals. The prosecution had a flawless day on both counts Wednesday.

Greg Jolley says

Fine coverage. Thank you.