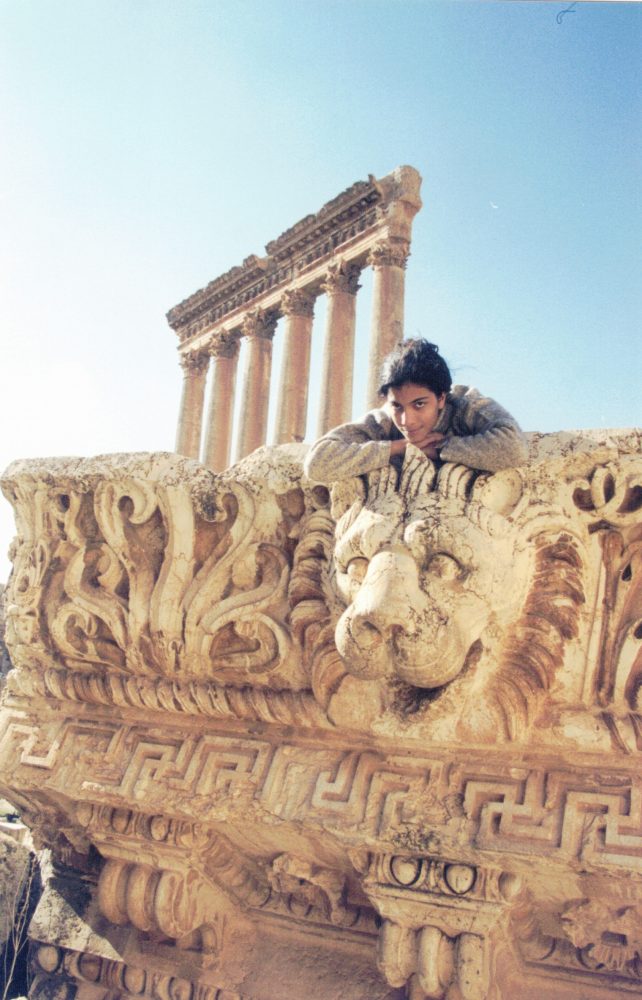

In 2011, when I had reached the age that took my dear father Fouad’s life (46), I wrote a piece about one of my fondest memories with him: our rare trips to Baalbek, city of Roman ruins at the northeast edge of Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley.

The Bekaa is Lebanon’s granary, a vast flat Great Plains in miniature, a high plateau of Iowa-grade arable land for millennia given over to growing the hashish that gave the Assassins their name, but also wheat, citrus, veggies and grapes for Lebanon’s great wines. Baalbek sits at the Bekaa’s northeast edge, at the foot of the snow-capped Anti-Lebanon mountain range, a name that puzzled me as a child since the range was inside our borders. Why the antagonism?

The Bekaa is Lebanon’s granary, a vast flat Great Plains in miniature, a high plateau of Iowa-grade arable land for millennia given over to growing the hashish that gave the Assassins their name, but also wheat, citrus, veggies and grapes for Lebanon’s great wines. Baalbek sits at the Bekaa’s northeast edge, at the foot of the snow-capped Anti-Lebanon mountain range, a name that puzzled me as a child since the range was inside our borders. Why the antagonism?

Then I learned that westerners, the same westerners who came up with the geographic hierarchies of “Middle East” and “Far East” in relation to Heliocentric Europe, had called it “Anti-Lebanon” in opposition to the equally majestic Lebanon Mountains on the other side of the valley to the west–the range that crests with Sannin’s 8,600-ft. summit. (Sannin was my surest thing as I grew up during the war years, the first thing I saw every morning.)

Geographically Baalbek was a short distance on the other side of Sannin, maybe 50 miles from our home in the mountains. But it might as well have been Troy. In Lebanon every mile mile is an odyssey of physical, tribal, sectarian and cultural twists. Like the country’s history. The original Baalbek settlement dates back 8,000 or 9,000 years. It is among the oldest on earth. It rose from the plains like a butte. Ancient settlers with an eye for strategy or ritual claimed it.

Astarte, the Phoenician goddess of war, sex and chariots was worshipped there with hymns, dancing, cymbals and wine. The Greeks during Alexander’s time built temples there, calling the place Heliopolis (“City of the Sun”). Roman emperors from Julius Caesar to Vespasia (who has his own engraved dedication there) to Trajan to Caracalla built the temples to Jupiter and Bacchus, garrisoning their legionaries around them. Baalbek became one of the Roman Empire’s most massive complexes.

The city grew below as it maintained its strategic gatekeeping into or out of Syria on the other side of the Anti-Lebanon and to the north. It was a Christian, Byzantine city until the early Muslim conquests of the 7th century. It has been a Muslim city almost uninterruptedly since, though hardly at peace as Seljuks, Sunnis, Fatimids (their era’s Shiites), Ottomans and other pretenders to Muhammad’s message, along with the occasional sacking by Byzantines and Tartars, occasionally made the city’s residential canyons a Venice of blood. It was somewhere in Baalbek that Saladin, that unusually humane and hesitant reconqueror, grew up. Before kicking European ass, Baalbek’s wine and women had been Saladin’s formative intoxicants. And who can blame him. The sensuality of those Roman colonnades is not a coincidence.

It’s a paradox: the ruins endure better than their surroundings. It is part of Lebanese lore and delusion that when we visited we considered ourselves less tourists than descendants. We could not control our present. So we claimed the past. In Beirut we pretended to be Phoenicians. In Baalbek we were Romans.

A photographer by trade, my father expressed his love for the ruins with his cameras. He shot them with the affection of a curator flirting with his patrimony. A bohemian at heart, he loved the wines (Chateau Musar), he loved the openness, a feeling I think I recovered when I found myself in America’s Great Plains, the way I recovered my father’s soul when I was in Baalbek in 2000. A line from Willa Cather’s My Ántonia: “Look at my papa here; he’s been dead all these years, and yet he is more real to me than almost anybody else. He never goes out of my life. I talk to him and consult him all the time. The older I grow, the better I know him and the more I understand him.”

Baalbek itself is quite the modern city, as populous as Palm Coast, if of course a bit older but no less of a promiscuous sprawl exploiting the emptiness around it. The elevated ruins aside, Baalbek spreads, it doesn’t rise. Only the Anti-Lebanon stops it, the way the mountains around Phoenix stop that gluttonous city. Baalbek has remained one of Lebanon’s major tourist attractions even though it’s smack in the middle of Hezbollah country. The Shiite majority dominates there just as its Fatimid ancestors had a thousand years ago, and cares for the ruins with the reverence due a fantastic revenue source, next to hashish.

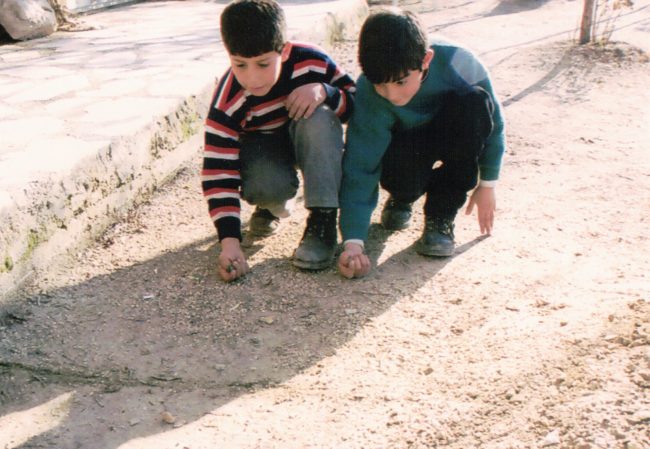

Overlooking Hezbollah’s morbid propaganda, I went to Baalbek that last time as much to see the ruins as to recapture memories of my dad, engraved as they are in the granite, in the leaning of that particular fallen column against a standing wall of the Temple of Bacchus, in the gleam of a turbaned man’s eyes–not that my father ever wore a turban (other than when he tried appropriating the local dress in his Yemen days). He’d have pointed his camera at that man and shot, and shot, and shot. The man would have smiled indulgently, muttering something to himself about the urban stupidity of Beirut’s day-trippers. Every visitor an exploiter. My own shutter found a pair of children playing with marbles exactly as I used to–same crouch, same expressions, same flicks of the fingers. Same hair. Same ancestry. Same dust.

Roman ruins are a cultural heritage, a UNESCO heritage site, an Oedipal remix of memories. But now once again, there are today’s ruins, the ruins around the ruins, the ruins of Baalbek the city, of Baalbek the sprawls, the inhabited homes, the restaurants, the schools, the walls and roofs of children’s future memories exploded and shattered by Israel’s latest razing, with some of these children, the children of my marble-playing children, still under them.

Now there is this, as reported by The Times on the day when America celebrated Thanksgiving: “A day after a cease-fire ended Lebanon’s deadliest war in decades, tens of thousands of people who fled the violence had already returned on Thursday to the hard-hit city in the country’s east. … after weeks of pounding Israeli airstrikes, the scars were not easy to ignore: bombed-out restaurants, flattened apartment buildings, trees snapped like twigs. And many of the dead were still buried under the rubble, residents said. ‘I’m an old woman. I’m not affiliated with anyone. What did I do to deserve this?’ said Taflah Amar, 79, as she swept debris from the front of her house, one of the few still standing on her street. ‘I’ve been crying all day,’ she said.”

Israeli cruelty has no bounds, so it’s a wonder the Roman ruins weren’t pulverized, leveled at one blow as two millennia could not level them. And for what? Baalbek is too far away from even the northernmost reaches of Israel to threaten it with missiles. It’s not as convenient as Damascus Road further to the south if it’s weapons shipments from Syria that Israel is worried about. Baalbek’s population, historically speaking, is no more in sympathy with Hezbollah than it had been with Ottoman Turks or Tamerlane’s Mongols or Byzantium’s Christians and whoever else occupied it, sacked it, razed it. That population is no less hostage to Hezbollah than Hamas’s Israeli hostages are in Gaza. But it’s no license for brutes to add to the local population’s misery.

The clandestine shipments of arms to Hezbollah from Iran and Syria are no less criminal, and ridiculously less lethal, than the unimpeded shipments of arms to Israel by sea and air and godspeed from American factories glittering with thanksgiving and Christmas decorations and USA Pride stickers as hard-working fathers and mothers digesting holiday cupcakes assemble the tonnage of mass murder for transfer to our 51st state before clocking out to F-150 their kids to soccer practice or check in at the PTO or Rotary, worship with emotive thoughts and prayers, volunteer a few hours at the food bank, instagram a couple of selfies from a binge at the outlet stores, scroll the news and tap like after like of indignation at those barbarians firing missiles at Israel.

To call it a razing is an exaggeration. Most of Baalbek is still standing. So are the last six remaining columns of the Temple of Jupiter, that symbol of Lebanon as undying as its cedars. The Baalbek death toll is between 50 and 60 at last count, relatively modest compared to the nearly 3,500 Lebanese who have been killed and 15,000 wounded since Israel began its latest assault on the country on Oct. 1 (to say nothing of the genocidal death toll in and actual, literal razing of Gaza).

Latest, because we long ago lost count of the number of times Israel has invaded, bombed, raped, massacred and flattened various parts of this collateral shrug to its barbarism since 1978. There’s something a little warped about remembering Baalbek’s Roman ruins so sentimentally in all this, as if to cling to something that maybe never was, at least for us contemporaries. But what else do we have? “Some memories are realities, and are better than anything that can ever happen to one again,” goes another line from My Ántonia, maybe explaining the impulse to remember as an act of resilience or rebellion against helplessness. But only those of us in the roofed and untroubled comforts of a Palm Coast or a Red Cloud can take comfort in a thought like that. It cannot possibly have the same resonance, the same vanity, under the rubble.

![]()

Pierre Tristam is the editor of FlaglerLive. reach him by email here.

Alan says

What? who cares about this type of publishing. This Is the USA

R.S. says

Good god, man! The USA is a tiny bird poop in light of the many cultures and their memorial ruins the world over. You should see the Roman ruins of North Africa, including Leptis Magna, the birth city of the Black Roman emperor Septimius Severus with his triumphal arch. The cement the Romans used still has cohesion even in the dry desert air, while western built buildings begin to decompose a decade after having been built. Stepping into the arena at Leptis Magna, one cannot help but feel the awe of the place, including the chariot racing ring outside between the Mediterranean and the arena. Governmental buildings of Washington are inspired by these African and Roman cultures. I’d be ashamed of such a limited view from a boarded-up brain. Thank you, Pierre, for putting matters into the right perspective.

Jake from state farm says

Beautiful article Pierre. I do love hearing about your homeland from your perspective. Lebanon and it’s people have been and are going through hell. I do appreciate your small mention of Iran and its culpability in all of this. I would expect that if Israel in striking it is because Hezbollah is hiding there, behind innocent civilians.

I love to read an editorial of Iran’s role in all this conflict from your perspective.

Kennan says

Well done! Beautifully layered historical perspective of a rich culture and proud people.

Just a note: Yes there is culpability on behalf of Iran, but we need to remember that if you look up “PROXY WARISM” ln the dictionary the U.S. and Great Britain are at the top of the list.

Just a note to you Alan. The USA has been around a mere 250 years. We could learn a lot from other “far older and sophisticated cultures “. Learning from history instead of shunning or mocking it.

In the”not so United States of America “ you are just renting space with the rest of us.

JOSEPH HEMPFLING says

I have been to baalbek many years ago upon my serving as a peace corps volunteer in rural turkey and upon my return home.

And can still vividly remember baalbek’s immense size of just about everything; manmuth stone columns, standing ruins, stand-alone spectacular location and while remembering all the past civilizations that it once was home to including turks.

And whose spirits visitors like myself brush up against until this day in our dreams and memories.

And I am praying that it survives and continues to stand firm against the madness of western cultures that think naively that it will conquer it. And the indomniable peoples who once called it home and still do.

And never will inshallah !

Brian Riehle says

Great story Pierre…Contrary to what Alan says, there are lot’s of people who care about stories like this, and a hell of a lot of others who should care about them. Sadly tho, most of your readers have zero knowledge about the history of the Middle East or Lebanon beyond maybe the last 20 years. I was in Beirut in 1958 and it was one of the most beautiful, friendly places I’ve ever been to, and watching what has been inflicted on the Lebanese people since then is a tragedy.

Everyone in the USA should care about Lebanon.