By Yvette Richardson and Paul Markowski

Storm-chasing for science can be exciting and stressful – we know, because we do it. It has also been essential for developing today’s understanding of how tornadoes form and how they behave.

In 1996 the movie “Twister” brought storm-chasing into the public imagination as scientists played by Helen Hunt and Bill Paxton raced ahead of tornadoes to deploy their sensors and occasionally got too close. That movie inspired a generation of atmospheric scientists.

With the new movie “Twisters” coming out on July 19, 2024, we’ve been getting questions about storm-chasing – or storm intercepts, as we call them.

Here are some answers about what scientists who do this kind of fieldwork are up to when they race off after storms.

National Severe Storms Lab

What does a day of storm-chasing really look like?

The morning of a chase day starts with a good breakfast, because there might not be any chance to eat a good meal later in the day.

Before heading out, the team looks at the weather conditions, the National Weather Service computer forecast models and outlooks from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Storm Prediction Center to determine the target.

Our goal is to figure out where tornadoes are most likely to occur that day. Temperature, moisture and winds, and how these change with height above the ground, all provide clues.

There is a “hurry up and wait” cadence to a storm chase day. We want to get into position quickly, but then we’re often waiting for storms to develop.

National Severe Storms Lab

Storms often take time to develop before they’re capable of producing tornadoes. So we watch the storm carefully on radar and with our eyes, if possible, staying well ahead of it until it matures. Often, we’ll watch multiple storms and look for signs that one might be more likely to generate tornadoes.

Once the mission scientist declares a deployment, everyone scrambles to get into position.

We use a lot of different instruments to track and measure tornadoes, and there is an art to determining when to deploy them. Too early, and the tornado might not form where the instruments are. Too late, and we’ve missed it. Each instrument needs to be in a specific location relative to the tornado. Some need to be deployed well ahead of the storm and then stay stationary. Others are car-mounted and are driven back and forth within the storm.

Yvette Richardson

If all goes well, team members will be concentrating on the data coming in. Some will be launching weather balloons at various distances from the tornado, while others will be placing “pods” containing weather instruments directly in the path of the tornado.

A whole network of observing stations will have been set up across the storm, with radars collecting data from multiple angles, photographers capturing the storm from multiple angles, and instrumented vehicles transecting key areas of the storm.

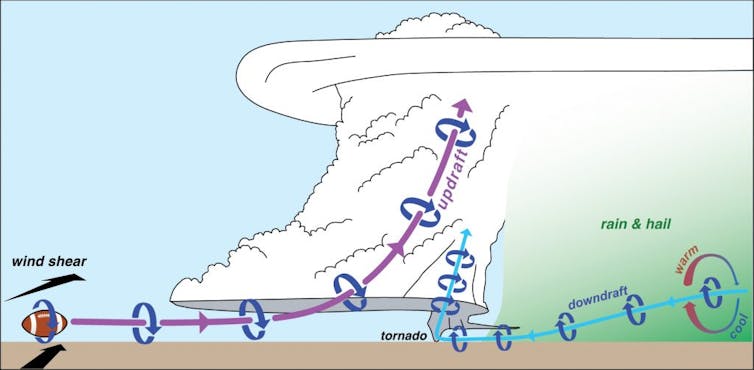

Not all of our work is focused on the tornado itself. We often target areas around the tornado or within other parts of the storm to understand how the rotation forms. Theories suggest that this rotation can be generated by temperature variations within the storm’s precipitation region, potentially many miles from where the tornado forms.

Paul Markowski/Penn State

Through all of this, the teams stay in contact using text messages and software that allows us to see everyone’s position relative to the latest radar images. We’re also watching the forecast for the next day so we can plan where to go next and find hotel rooms and, hopefully, a late dinner.

What do all those instruments tell you about the storm?

One of the most important tools of storm-chasing is weather radar. It captures what’s happening with precipitation and winds above the ground.

We use several types of radars, typically attached to trucks so we can move fast. Some transmit with a longer wavelength that helps us see farther into a storm, but at the cost of a broader width to their beam, resulting in a fuzzier picture. They are good for collecting data across the entire storm.

Smaller-wavelength radars cannot penetrate as far into the precipitation, but they do offer the high-resolution view necessary to capture small-scale phenomena like tornadoes. We put these radars closer to the developing tornado.

We also monitor wind, air pressure, temperature and humidity along the ground using various instruments attached to moving vehicles, or by temporarily deploying stationary arrays of these instruments ahead of the approaching storm. Some of these are meant to be hit by the tornado.

Weather balloons provide crucial data, too. Some are designed to ascend through the atmosphere and capture the conditions outside the storm. Others travel through the storm itself, measuring the important temperature variations in the rain-cooled air beneath the storm. Scientists are now using drones in the same way in parts of the storm.

All of this gives scientists insight into the processes happening throughout the storm before and during tornado development and throughout the tornado’s lifetime.

How do you stay safe while chasing tornadoes?

Storms can be very dangerous and unpredictable, so it’s important to always stay on top of the radar and watch the storm.

A storm can cycle, developing a new tornado downstream of the previous one. Tornadoes can change direction, particularly as they are dying or when they have a complex structure with multiple funnels. Storm chasers know to look at the entire storm, not just the tornado, and to be on alert for other storms that might sneak up. An escape plan based on the storm’s expected motion and the road network is essential.

Scientists take calculated risks when they’re storm chasing – enough to collect crucial data, but never putting their teams in too much danger.

It turns out that driving is actually the most dangerous part of storm-chasing, particularly when roads are wet and visibility is poor – as is often the case at the end of the day. During the chase, the driving danger can be compounded by erratic driving of other storm chasers and traffic jams around storms.

What happens to all the data you collect while storm-chasing?

It would be nice to have immediate eureka moments, but the results take time.

After we collect the data, we spend years analyzing it. Combining data from all the instruments to get a complete picture of the storm and how it evolved takes time and patience. But having data on the wind, temperature, relative humidity and pressure from many different angles and instruments allows us to test theories about how tornadoes develop.

Although the analysis process is slow, the discoveries are often as exciting as the tornado itself.

![]()

Yvette Richardson is Professor of Meteorology and Senior Associate Dean for Undergraduate Education at Penn State. Paul Markowski is Distinguished Professor of Meteorology at Penn State.

SleepTech says

Your article is commendable and the research is necessary, however I take exception to the phrase “never” putting ourselves to close to the danger.

I lived in South Oklahoma City/Moore, Oklahoma and my house was less than a mile from the May 3rd, 1999 F5 tornado reported to be the costliest in American history. Over a mile wide it hit the Norman, OK weather station with wind speeds over 300 miles per hour.

I was also there for the 2 F5s that occurred May 2013 in and around Oklahoma City. We ultimately lost our home due to damage from those storms at a loss despite insurance. One of those tornados carved a path through Moore very similar to the 1999 path for several hours I knew the tornado had hit a high school, the news misspoke and for several hours I did not know due to down phone lines if my two oldest children were alive or dead. My youngest I knew to be okay because her teacher kept calling frantically for me to get her so she could leave to find her family. I was stuck on the north side of town.

I had sent my oldest daughter before the tornado formed to go get my middle daughter from high school. Schools in Oklahoma are not designed for tornados, yet kids are required to go to unsafe buildings during tornado season with no shelters on days we know have extremely high chance of tornado formation. This was one of those days. My daughter arrived at the school and a super cell had formed but there was no storm yet so they would not let my other daughter leave. My older daughter waited to try and reach me at work. A tornado formed. It was 20 miles away but growing in size I called her and told her to get in the building. She went back and the school would not let her in. She went back to her car, a mile wide tornado now headed for her. I’m now screaming for her to get out of there! She said “I can’t mommy, the hail is the size of baseballs now, it will kill me” and the line went dead. I’m panicking I grab my purse leave work not knowing and that’s when I hear the news say “Westmoor Highschool has been hit!”

I didn’t ask I ran out the door and in my car across town as best I could in traffic. Some rain, not too bad. Sky was green in that direction. Emergency vehicles kept coming so I kept having to pull over of course. I finally get to my neighborhood and see my father-in-laws truck (phone lines are down so I still can’t get a hold of anyone) he has my youngest. He asks if I want her. I don’t even think I was polite, probably shock I screamed “YES!” And grabbed her into the car and peeled off toward the house.

A couple streets more I pull into the driveway. My heart sinks as I realize they aren’t there and I am going to have to try and cross the over mile wide path that is nothing but dirt. The tornado had ground so much debris there wasn’t even foundations, just dirt in the path, no landmarks, no barns, no animals, no homes, no signs, no grass, no trees, just red dirt like being on mars. Then as I was getting ready to head back out of the driveway they pulled in, they were okay! The news channel we were watching misspoke, it was Southmoor that was hit and it was barely damaged. However that day an elementary school was hit and we lost 6 elementary school kids. A 7th later took his life. A news story later would report the school wasn’t even built to code!

During the 19 years I lived in Oklahoma City/Moore, Oklahoma I witnessed many tornados. I have to say in the beginning I found them fascinating, exciting even. I marveled at the power of Mother Nature and looked forward to tornado season. Gary England, the Meteorologist heard reporting on the original Twister movie, was our Meteorologist and he was extremely educational and calm.

I feel like I got a degree from him and while he was reporting I always felt we were in good hands. He was promoted and left the air.

I also watched a lot of storm chasers. I had a lot of favorites. Gary relied a lot on one named “Val”. Swinging back to my original issue with “never” putting ourselves in danger. When dealing with tornados you can never say “never” even when you are among the best. I watched with horror as 3 storm chasers from The Weather Channel lost their lives, and I think that was one of the 2013 tornados. They had the best equipment, it was recent so communication was good, it was a live feed sadly, it turned. There is so much we don’t know.

After what happened in 2013, after I felt like I could have lost my family. (My husband was fine too, he was just further away) After losing my house it was no longer exciting, it was no longer safe. I just wish the radar here was as good as the radar in Oklahoma.

Atwp says

Very exciting!