By Barbara A. Trish

Donald Trump is doing something new in Iowa.

The state is home to the first-in-the-nation GOP nomination event, the Iowa caucus, which takes place on Jan. 15 at 7 pm. Trump, the former president, holds a resounding lead over his rivals.

What’s new for Trump in this campaign is actually old stuff – a throwback to traditional caucus campaigning. I’ve observed Iowa caucus campaigns over eight cycles, and my 2022 book, “Inside the Bubble,” offers a close-up of the 2020 Democratic contest. Against that backdrop, it’s clear that the former president is taking cues from those who’ve come before him.

The widely accepted path to caucus success – first paved in 1976 by then-unknown Jimmy Carter on his way to the Democratic nomination and eventually the White House – is to “organize, organize, organize,” as many campaign staff will tell you. Since then, it’s been the mantra for candidates of both parties – and this year, that includes Trump.

But such attention to organizing is a shift for the Trump campaign. Today, it looks nothing like the scattershot campaign from 2016, the only other time Trump has waged a nomination battle in the state.

Scott Olson/Getty Images

Car rides, phone calls

A caucus in Iowa is a first step in a series of events that will ultimately select delegates to the national convention that formally nominates the presidential candidate. Unlike a primary, in which voters go to a polling place and cast a ballot, a caucus is a political party meeting at which people discuss the candidates and then vote.

Caucuses are held in each of the approximately 1,700 precincts in Iowa. Registered party members can participate in the caucuses, and attendees will signal their support by writing a candidate’s name on a piece of paper.

Organizing isn’t unique to Iowa caucus politics, and it means different things depending on the context. In electoral politics across the U.S., campaigns organize by doling out responsibilities to field staff positioned across a state or electoral district. These staff, then, amass volunteers to get-out-the-vote, either on election day or – in some states – in an early voting window before the election.

A typical organizing effort in caucus politics identifies early supporters of a candidate and asks them to be the foundation for a larger volunteer structure. These volunteers engage in outreach to other potential supporters – sometimes in-person, via door-to-door canvassing or on the phone, and increasingly by sending text messages. They’ll make sure that known supporters get assistance they might need to get to the caucus, such as a car ride.

The personal element of organizing is well-suited to caucus politics, which poses unique challenges to campaigns. Like primaries, caucuses are within political parties, so voters can’t rely on cues like party labels to pick a candidate. Instead, a friend or family member volunteering for a candidate just might be persuasive.

Caucus organizers can help voters navigate a byzantine process.

Unlike primaries, which involve a daylong window for voting, caucuses are scheduled for a specific day at sometimes obscure locations; this year’s Jan. 15 date coincides with Martin Luther King Day. Caucuses always start at 7 p.m., and they last as long as it takes to conclude business, which is likely an hour. This process can be intimidating, and effective organization can educate supporters and help ensure they show up.

Campaign bling

Trump’s nod to organizing is noteworthy and is at odds with his brand, which is more focused on stirring the pot and agitating, rather than painstakingly building an infrastructure.

Back in 2016, reluctant Trump volunteers, unfamiliar with caucus procedures, courted Iowa supporters. And while the headquarters of rival candidates were abuzz with activity, Trump’s was deserted. Trump came in second in that year’s caucus.

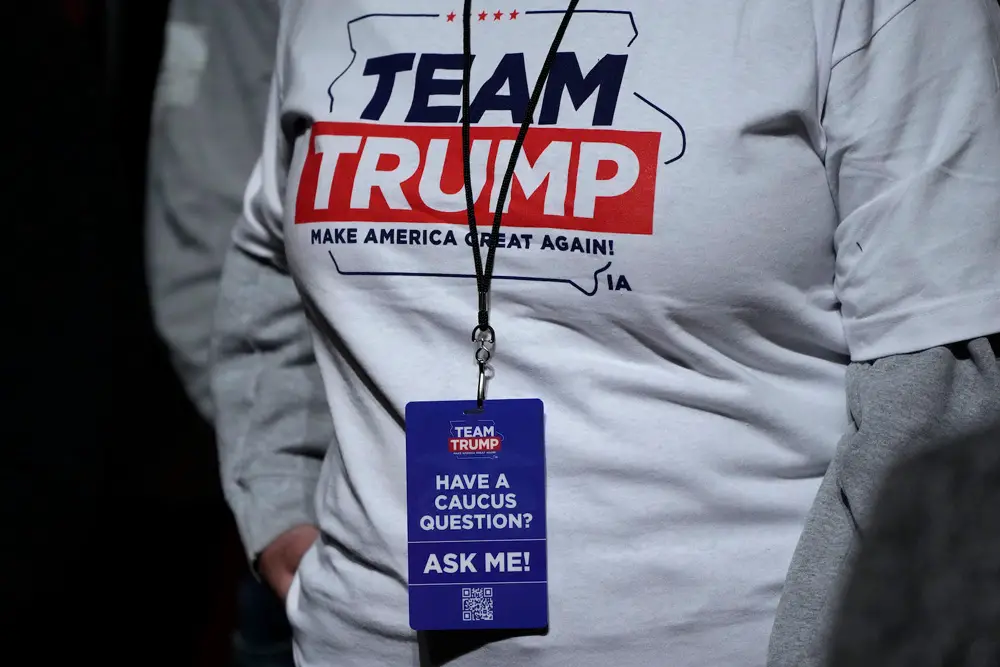

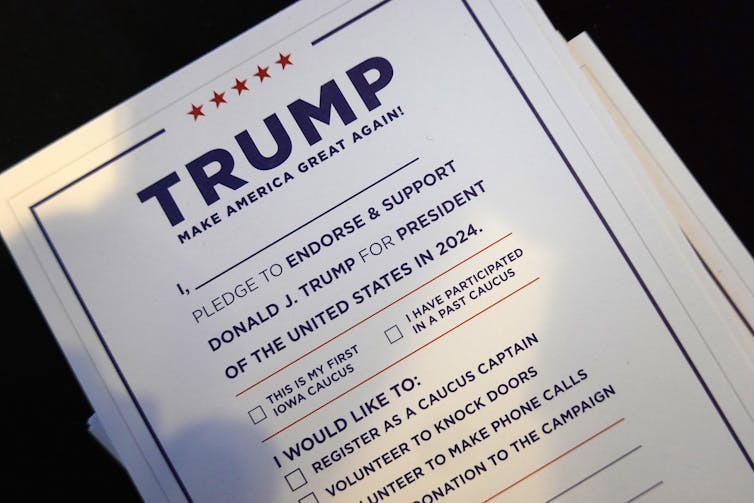

Now, Trump’s 2024 field army of some 2,000 caucus captains, many of whom have already gone through formal training, are the front-line recruiters in the lead-up to this year’s caucus. They carry out tasks on behalf of the campaign at events themselves. Lest this all seem overly staid, there’s bling, too – a limited edition white and gold variant of the distinctive MAGA cap for the captains.

Of Trump’s GOP rivals, it’s Vivek Ramaswamy, the young biotech entrepreneur new to politics, who’s working the hardest to meet Republican activists face to face. With a schedule packed with “town hall” appearances, as many as eight or nine daily, Ramaswamy is on the Pizza Ranch circuit, taking advantage of the community rooms in the Iowa-based restaurant chain with a Christian conservative corporate vision.

Caucus 101 lessons

Trump’s caucus events are different. They’re large rallies with hundreds in attendance – and since mid-October, most of them are billed as “Commit to Caucus” events. The events have considerable time devoted to instructing the crowd about how to caucus, which is an unusual use of time at campaign events. It’s also a little perplexing, but potentially conveys some meaning.

The typical rally requires attendees to register and be in place well before the event begins, perhaps 1-2 hours early. Attendees are primed with a playlist and some B-list endorsers. They have included a losing congressional candidate, Trump’s former acting attorney general after he fired Jeff Sessions, and the Iowa attorney general.

Despite Trump’s commanding lead in the polls, local GOP stars – like Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds and prominent Iowa evangelical leader Bob Vander Plaats – are on Team (Ron) DeSantis.

But early in these Trump rallies, the program pivots to a Caucus 101-like presentation – how to find out where to caucus, what to do in advance and what to expect at the caucuses.

The other GOP candidates do this at their events to a much lesser extent, if at all. And in a heavily reported gaffe, Casey DeSantis, the spouse of the Florida governor, actually conveyed incorrect instructions, saying that non-Iowans can participate in the Iowa caucuses.

The how-to-caucus component of Trump campaign events could be nothing more than filler, something to occupy the attention of a confined crowd forced to be in place for hours. It might even be ill-advised, patently naïve because it’s instructing not only Trump supporters, but also Republicans in other candidates’ camps. When Democratic candidates have offered such instruction in the past, it’s been behind closed doors, reserved for known supporters and closer to caucus time.

It’s just possible that there’s more to this, some deeper meaning in the former president signing off on an effort to build an organization. Perhaps he recognizes that celebrity will only take him so far, and that attention to the traditional tools of politics might be in his best interests.

In that spirit, last summer Trump’s campaign scored a big win in California, where it successfully pushed for Trump-friendly processes in that state’s winner-take-all presidential primary. Whether simply finding ways to modify rules to his advantage – or flat-out rigging the system – this new Trump approach is time-honored.

And it just might give Democrats even more cause for concern. A second term might be fueled with a little more political know-how to advance the Trump agenda.

![]()

Barbara A. Trish is Professor of Political Science at Grinnell College.

Leave a Reply