In the end, it was not even close: after five days of trial and just two hours and 20 minutes of deliberations, a jury reached a verdict that found Robert Barry didn’t so much have good reason to believe that that a fellow-Publix employee had been sexually harassed by a supervisor. That Barry, in other words, had fabricated the story.

That made moot every one of the remaining eight questions the jury was facing–whether Publix had wrongfully fired Barry, whether it had maliciously covered anything up, whether he was owed any back pay or any kind of compensation. The victory could not have been more decisive for the Lakeland-based company, which seldom goes to trial, and did so in this case as a result of a succession of incidents that took place at the Town Center Publix in Palm Coast in early 2010.

As a clerk read the jury before Circuit Judge Michael Orfinger in a Flagler courtroom this afternoon, Barry and his attorney Frederick Morello sat side by side, motionless, Barry’s head tilting down almost imperceptibly and his his eyes blinking repeatedly. Neither reacted beyond that. There was no contact between the two before, during and after the verdict was read. Not so much as a pat on the back, as lawyers disallowed a victory hug are often wont to do for their client in a losing case. The only visible physical reaction from Morello, who’d invested four years in the case, was his left ear, which turned a deep crimson as he asked for the jury of four women and two men to be polled. (The alternate, a woman who’d filled three legal pads full of notes and posed numerous written questions during the trial, had been excused just before the deliberations, though she sat in the courtroom to hear the verdict).

Brown said the harassment never took place. Eight other witnesses, including internal investigators, Pryor and other Publix employees corroborated or agreed with her claim.

The company said Barry fabricated the story with fellow-employee Henry Torro because the pair didn’t like Dario. The two men knew that an accusation of sexual harassment was among the gravest that could be made against a manager, and that it could lead to his firing. The plan backfired. During the investigation Publix learned that Barry had lied on his employment application, never disclosing that he’d been arrested for pot possession and obstruction of justice.

One of the charges was itself the direct result of a lie: Barry had lied about his name and birthdate to a cop.

That fact was not known to the jury until today. The jury knew that Barry had been involved in a legal matter, but until today thought it had to do with a traffic matter. Today it learned that it wasn’t just a traffic matter: Barry had driven away from an accident involving a death. And, in a separate matter, he was arrested on the pot possession and obstruction charges. The revelations, a victory for Publix’s defense, were disclosed during a stunning, brief procedure called a proffer–that is, the tendering of evidence, often designed to ensure that all relevant evidence is presented in case of an appeal–immediately before closing arguments, though until today Morello had successfully kept the details out of play.

(© FlaglerLive)

One of the key turning points of the trial in the jury’s mind was Michelle Ashton Brown’s 75-minute testimony (as indicated by the only question the jury posed during its deliberations: it wanted a full transcript of Brown’s testimony. The judge, with both attorneys’ agreement, declined to provide it, saying it would take at least two hours to prepare). Brown is the woman who Barry said was allegedly harassed.

Brown is a young, assertive, pretty and outspoken woman who described herself as a country girl, and who advertises to the world that her nickname is “Biscuitbutt.” The nickname is plastered on the front of her truck. She concedes that co-workers often referred to her by that nickname, and even by other variants of the word “butt,” including “Ass-ton,” a play on her middle name, none of which offend her. But she adamantly said sexual harassment never took place. She did so in a written statement that would become central to the Publix defense, as was Brown’s often funny but unimpeachable–and more notable for the jury, unimpeached by Barry’s attorney–testimony.

Absent even a hint of support from Brown, Barry’s attorney built a case around Barry and Toro, his two chief but wobbly witnesses, to claim that Publix had intentionally used the story of Barry’s dishonesty as a shield for the company’s own cover-up.

When Barry reported the alleged harassment, Morello claimed, Pryor, the store manager, and her district manager allegedly circled the wagons. Barry had used the company’s open-door policy to report what he saw as a wrong, and the company instead used that open-door policy as a shield, to concoct a cover-up and protect Dario, who Morello said during closing arguments–for the first time to the jury’s ears–was being groomed as a store manager and should be protected. Yet there’d been no evidence to that effect in the previous days of trial. It sounded like one of several straws the attorney was grasping for during his closing arguments. There’d been a lot of straw-grasping in the previous four days, too.

The closest Morello came to suggesting (rather than actually showing) that there may have been an attempt to downplay the sexual harassment claim was that Pryor and Brown’s mother had worked together for years, and were friends at work. But even that claim of collusion–denied by all Publix witnesses and unsubstantiated by any documentation–seemed more like a stretch, even as an assumption, since Brown and her mother had nothing to gain from covering up an allegation against Brown, and both may have had a lot more to lose: an employee hiding a case of sexual harassment is no less subjected to potential discipline than one committing such an act, according to Publix policy.

Morello was reduced in his closing arguments to raising questions in jurors’ minds in hopes of giving weight to assumptions he had not proven: why was the store manager involved in the investigation? Why didn’t Publix get statements from all parties involved? Could the store manager have been “steering” the investigation? Why did she get an email to her private rather than business account from the woman at the center of the sexual harassment allegation? “Is it because Miss Tripp [Brown’s mother] and the store manager were buddies and they were trying to manipulate the investigation from the outset?”

That was the best Morello could do: raise questions rather than answer them based on solid evidence he’d secured during trial. Morello, whose tone in closing occasionally relied on sarcasm and approached contempt for Publix, called the company’s appeal process when an employee is fired a “kangaroo court,” because the appeal is conducted by Publix management rather than independent investigators. That, too, may have come across as a gratuitous attack on the company’s internal procedures rather than a substantiated claim.

Publix attorney William Reese raised few questions in his closing arguments. He answered them, with damning statements based on evidence testimony presented and left undisputed, starting and ending with Barry’s dishonesty. “He even lied to you under oath. This is why this case is all about honesty. Mr. Bary simply does not tell the truth,” Reese said.

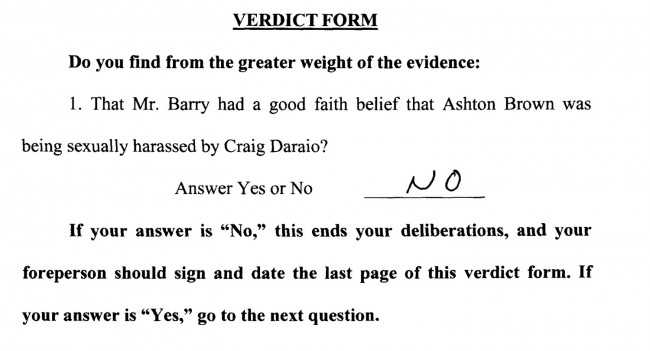

The jury went into deliberation room with a list of nine questions. But it did not necessarily have to answer all nine. The moment it answered no to any of the questions, the remaining questions would be made moot, starting with the very first one: “Do you find from the greater weight of the evidence, one, that Mr. Barry had a good faith belief that Ashton Brown was being sexually harassed by Craig Dario.”

If the jury answered no to that first question, as it did, the case was over. If the answer had been yes, the next question had to be answered: “Do you find from the greater weight of the evidence that Mr. Barry’s belief that Ashton Brown was being harassed by Craig Dario was reasonable under the circumstances, yes or no.”

And so on. It never got nearly that far.

The jury went into deliberations at 12:20. There was a telling moment a little after 1 p.m. when Judge Orfinger reconvened court to hear the only request a juror would make–the one for Brown’s full testimony. Reece and Kelly, the Publix lawyers, were quickly in their seats and the jury was about to be called in. Morello, who was at lunch, was patched in by phone to be informed that a question was to be posed. The judge asked him how soon he could make it back into court.

“We just sat down to eat,” Morello told the judge, suggesting the proceedings could go on without him. “I trust you, judge.” The judge kept him on the phone and called in the jury to answer the question.

The only other remarkable thing that happened during the 140-minute recess before the verdict was court reporter Shannon Green distributing plum cake–made with plum baby food, with her mother Terry Green’s recipe–to the few people who’d shared the courtroom for what equated to nearly 30 hours over five days. In the scheme of that five-day trial, it was the day’s only surprise.

![]()

groot says

In case any current or future employers didn’t know who Mr Barry is, they do now. He has done himself a huge disfavor and destroyed his future credibility. All this over a grocery store job?

Booblix says

This should have never made it to court.

jbeagles says

what a waste of the courts time and resources.

Dave says

I say to Publix and those he accused, sue Mr Berry for slander and bankrupt him forever.

TBG says

Many women have won big with far lesser proof and even less in the way of common sense. That is why Publix chose to fight and rightfully so. Sadly, in our legal system today, given the same facts, gender of the accuser is the deciding factor.

Pay us back says

Who gives a flying …..fudge ? Why were the taxpayers money WASTED on this nonsense ? I WANT MY MONEY BACK NOW !!!!!