By Natalia Soares Quinete and Olutobi Daniel Ogunbiyi

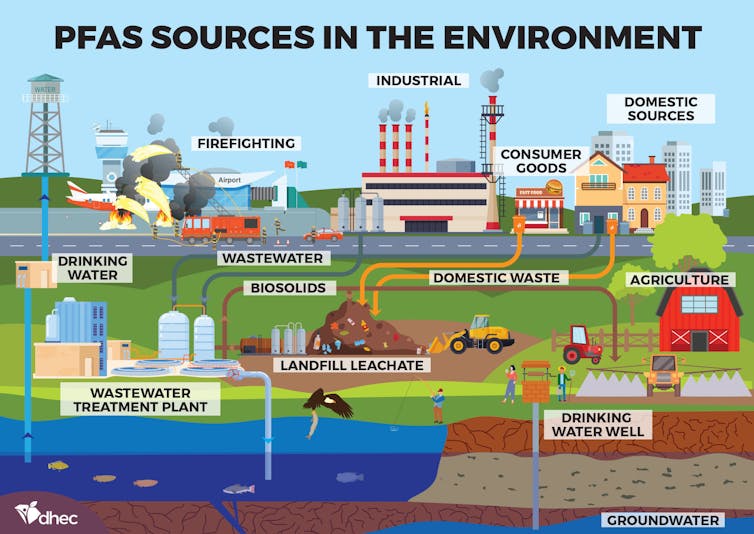

PFAS, the “forever chemicals” that have been raising health concerns across the country, are not just a problem in drinking water. As these chemicals leach out of failing septic systems and landfills and wash off airport runways and farm fields, they can end up in streams that ultimately discharge into ocean ecosystems where fish, dolphins, manatees, sharks and other marine species live.

We study the risks from these persistent pollutants in coastal environments as environmental analytical chemists at Florida International University’s Institute of the Environment.

Because PFAS can enter the food chain and accumulate in marine plants and animals, including fish that humans eat, the spread of these chemicals has ecological and human health implications.

NPS image by Shaun Wolfe

In a new study, we traced the origins of PFAS contamination in Miami’s Biscayne Bay to help pinpoint ways to reduce the harm.

What are PFAS?

PFAS – perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances – are a group of human-made contaminants that have been used for over 50 years. They’re found in personal care products, such as cosmetics and shampoo, and in water-repellent coatings for nonstick cookware and food packaging. They’re also used in adhesives and aqueous firefighting foams, among other products.

As those PFAS-containing products washed down drains and were thrown in landfills over the years, PFAS chemicals became widespread in the environment. Eventually, these chemicals found their way into aquatic ecosystems, including surface water, groundwater and coastal environments.

North Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control

The same stability and resistance to degrading that makes these chemicals valuable for water- and stain-proof products also makes them nearly impossible to destroy. Hence, the nickname “forever chemicals.” They persist in the environment for decades to centuries.

That’s a problem, because PFAS have been linked to immunological disorders, endocrine, developmental, reproductive and neurological disruption and increased risk of bladder, liver, kidney and testicular cancer. A drinking water study by the U.S. Geological Survey estimated these chemicals were in at least 45% of tap water across the U.S., and a large percentage of Americans are now believed to have PFAS detectable in their blood.

Studies have also found PFAS in a broad range of marine wildlife, including in the livers of otters and in gulls’ eggs, as well as in freshwater fish across the U.S. These chemicals have already been shown to affect the immune system and liver function of fish and marine mammals.

How PFAS get into the marine environment

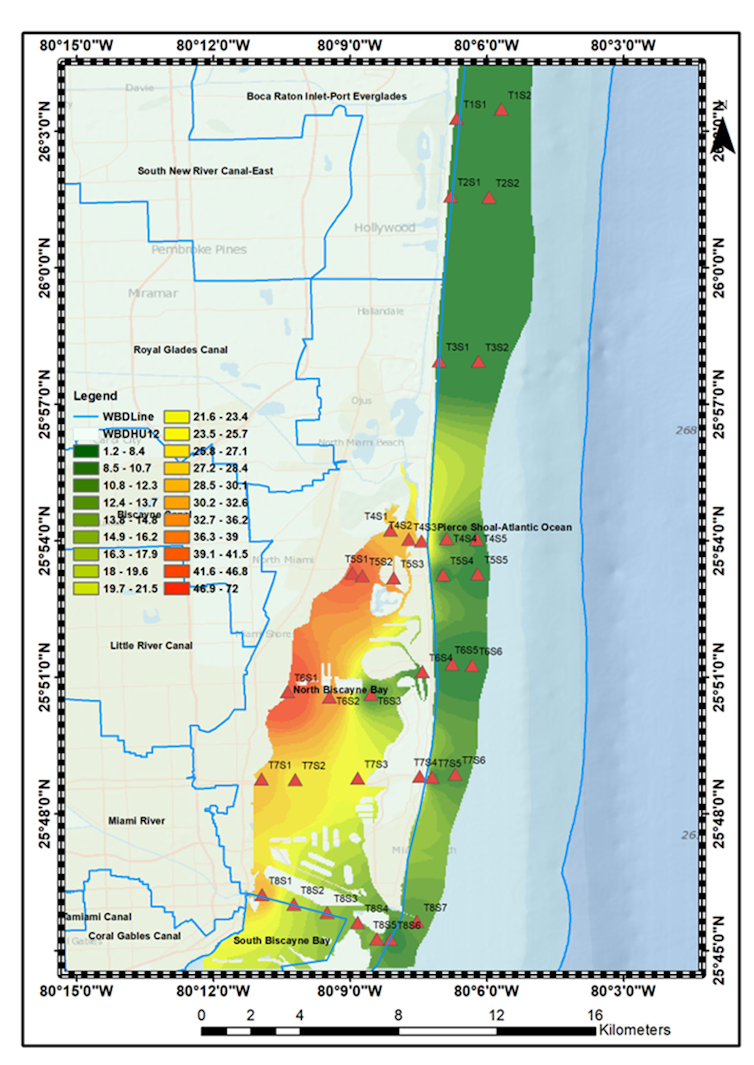

When we began tracking the sources of PFAS in Biscayne Bay, we found hot spots of these chemicals around the exits of urban canals – especially the Miami River, Little River and Biscayne Canal. Each of these canals, we found, is a major point source contributing to the presence of PFAS in offshore areas of the Atlantic Ocean.

One major source of that PFAS is sewage contamination from failed septic systems and wastewater leaks in urban areas. This is evident by the presence of the types of PFAS – such as PFOS, PFOA, PFPeA, PFHxS, PFHxA, PFBA and PFBS – that are used as stain and grease repellents and in carpets, food packaging materials and household products.

Another major source is represented by the predominance of 6-2 FTS in the Miami River – 6-2 FTS is a fluorotelomer PFAS typically used in aqueous film-forming foam found at military and airport facilities. The Miami River flows past rail yards, industries and Miami International Airport on its way to Biscayne Bay.

CC BY-ND

We also used a model to predict how ocean currents would disperse PFAS coming out of those canals and into coastal areas. We found that the PFAS concentrations were highest close to the canals, decreased along the bay and declined as ocean water became deeper and more saline, which makes PFAS less soluble in water.

Overall, PFAS concentrations were almost six times higher in surface waters near land compared with deep-water samples collected 13 to 33 feet (4 to 10 meters) below the surface in the bay and offshore. That suggests the highest risk is to pelagic fish that hang out in surface waters, such as mackerel, tunas and mahi-mahi.

How marine organisms are at risk

The levels of PFOS and PFOA in our study were below the Florida Department of Environmental Protection advisory levels in surface water for human health exposure. However, the advisory levels might not be protective of human and marine life.

They do not take into consideration that these chemicals accumulate through the food chain. Higher concentration in the top of the food web means PFAS could pose a greater risk to dolphins, sharks and humans that consume fish.

CC BY-ND

Many types of PFAS identified in our samples are not regulated, and their potential toxicity is unknown. We believe there is a need for federal and state agencies to develop guidelines and implement action plans to protect people and the aquatic life in Biscayne Bay.

What you can do about it

Given the persistence of PFAS and their widespread use, it is not surprising that these forever chemicals are found in almost all water systems in South Florida and are showing up in coastal waters around the world.

While scientists look for effective and efficient ways to eliminate and remove these chemicals from water, food and the environment, people can limit their use of PFAS-containing products to reduce the amounts of these chemicals that get into the marine environment.

Here are some common products that contain PFAS to watch for: Teflon nonstick cookware; food packaging for fast food and popcorn; water-resistant clothing and cosmetics; and treated carpets.

![]()

Natalia Soares Quinete is Assistant Professor of Chemistry at Florida International University. Olutobi Daniel Ogunbiyi is a doctoral candidate in Chemistry at Florida International University.

Pogo says

@A good source of information about this matter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark_Waters_(2019_film)

As Thanksgiving Day approaches

Laurel says

Okay, for starters, there are very few, if any, septic systems in Miami, so that is not a major source. I worked in a city smaller than Miami, but still considered a highly populated area, and I tracked septic tanks. There are very few in my city, so to say it’s a major source of pollution in Miami, is not accurate. It is true that the state does want to remove all septic tanks over time.

My husband worked for this city, and in private industry, in the utilities underground business. It is not uncommon for sewer force mains to break and spill out thousands of gallons of raw sewage onto the roads and/or the ICW. It is also common to pour treated water into the ICW, sometime a couple times a year, depending on capacity and need. It may be treated, but it is considered non potable and contains these chemicals.

One of my jobs was public education. I was to convince people not to use storm drains for anything other than rain water, yet people would wash their cars right over these drains that were connected directly to the ICW, just a few feet away. I did comic books, brochures and booth events to educate people to understand PPP (personal pollution prevention) as there are many things people to do to reduce pollution. Some are: don’t fertilize or spread pesticides before a rain event. Don’t dump plant debris in canals or swales. Don’t blow leaf debris and grass clippings into storm drains, rivers, canals and swales. Clean up waste after your pet. We also did public service messages on local cable TV. I see no public education in this area.

Other than that, municipalities and counties need a permit to discharge rain water and treated water into the waters of the U.S., and that permit is called the NPDES Permit. NPDES stands for National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System. I wrote that permit annually.

We are all responsible, but I hold the big corporations responsible as they continue to promote these chemical filled products to the public and to businesses. If they would provide better products, and we practice PPPs, we could reduce these chemicals in our waters.

Endless dark money says

Chemical companies spend hudreds of millions to prevent any regulation of their for profit poison. They will change the formula if needed as regulation is 3 decades behind. Republicons don’t believe in poisoned water. Good luck water drinkers. Your new cancer isn’t because of the toxic environment….now pony up your life savings for treatment if you can afford it.