In a case involving a former Orange Park councilman, a Florida appeals-court judge Wednesday blasted a landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling on the First Amendment. Judge Brad Thomas of the 1st District Court of Appeal wrote an 11-page concurring opinion that took aim at the Supreme Court’s unanimous 1964 New York Times v. Sullivan ruling, which, in part, required that public officials prove “actual malice” to prevail in defamation lawsuits.

Thomas cited other critics of the ruling, including current Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, and said New York Times v. Sullivan “was wrongfully decided and was not grounded in the history or text of the First Amendment.”

Public figures, the judge said, “should not have to prove that the alleged defamation was made with the knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of the truth, as this is an ‘almost impossible’ burden.” The “almost impossible” clause are the words of Justice Byron White, who was part of the unanimous decision for The New York Times, and is here used out of context, and against the meaning of White’s words when he wrote them in a 1985 decision. (White had not even filed a concurrence in 1964.) White never disputed the purpose of the Sullivan decision, only its method. “In New York Times, instead of escalating the plaintiff’s burden of proof to an almost impossible level, we could have achieved our stated goal by limiting the recoverable damages to a level that would not unduly threaten the press,” White wrote in the 1985 Dun & Bradstreet decision.

Thomas continued: “The decisions in New York Times and its progeny have established an environment in which anyone who might enter the public arena knows that they may be injured by defamation for which there is effectively no legal recourse,” Thomas wrote. “In addition, it has led to the destruction of reputations of many who never consented to becoming a so-called ‘public figure.’ No doubt this state of affairs since 1964 has diminished the public good from civic-minded citizens who understandably decline to offer their insights, energy, and wisdom to their fellow citizens, given this legal environment.”

Thomas’s concurring opinion lacks evidence and context. It’s difficult to prove reckless disregard and malice, but to say that public officials have “no legal recourse” is not borne pout by the record. For example, in 2017, Flagler County’s attorney successfully argued that former Flagler County Supervisor of Elections Kim Weeks, Mark Richter Jr. and Dennis McDonald had filed complaints containing knowingly and recklessly false allegations about local elected officials, who were public figures. A judge ordered the three to pay the county thousands of dollars in attorneys’ fees.

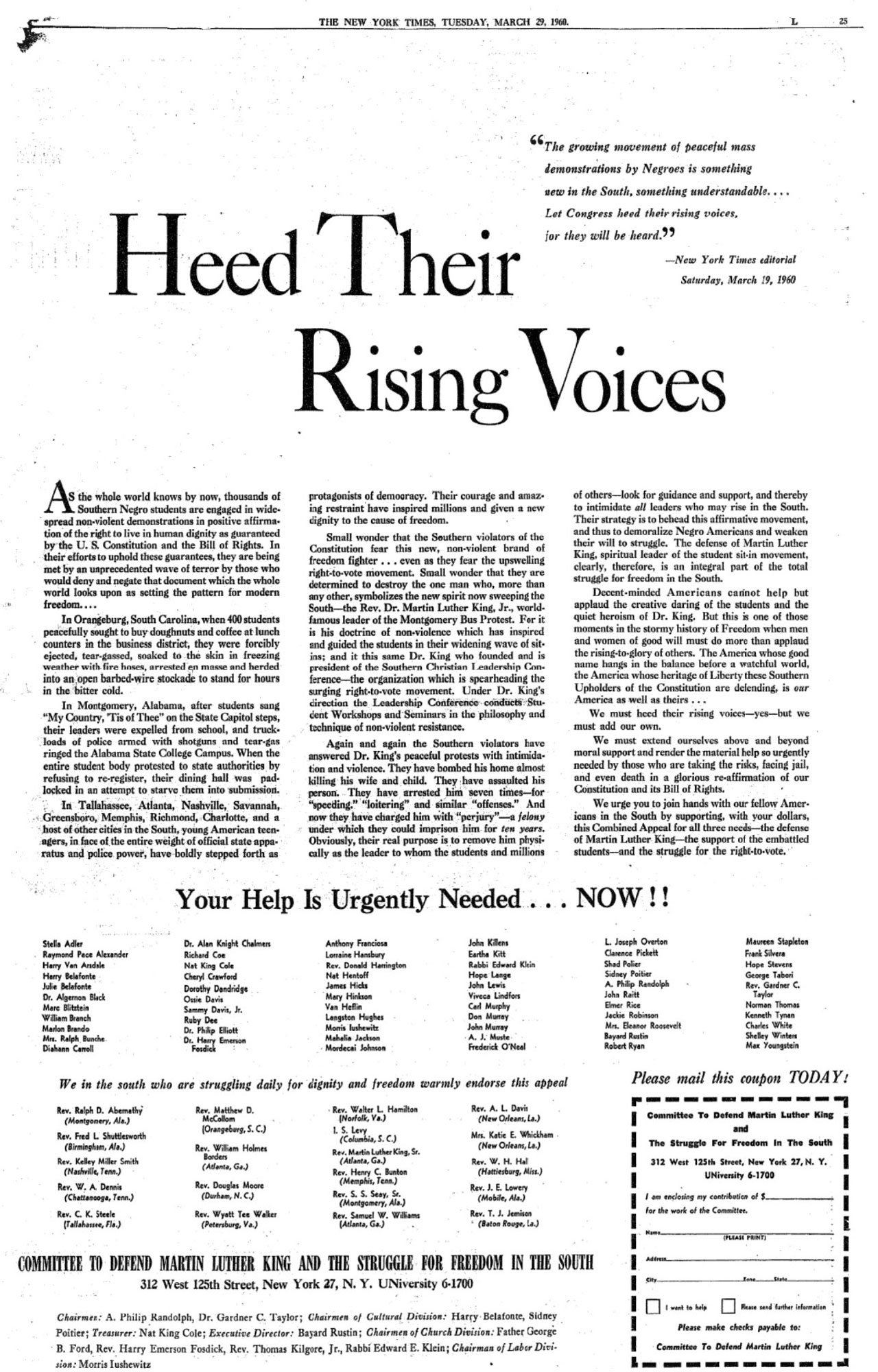

The context of the New York Times case, in the midst of the battle for civil rights in the South and governments’ attempts to silence the press, played a sizeable role in the reasoning behind the decision. L.B. Sullivan, the Montgomery city commissioners who filed the suit against the Times, was not named in the fund-raising advertisement that he said defamed him, and that had appeared in the pages of the Times (you can see and read the advertisement in the image above, or here or in the original newspaper issue here, on page 25). Nor did he show any damage from the advertising.

The ad referred to non-violent protesters against segregation being met with “an unprecedented wave of terror.” The ad unquestionably contained minor errors. It said student protesters had sung “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee.” They had not. They had sung the national anthem. It said the students had been expelled from school for demonstrating at the state capitol, though in fact they’d been expelled for holding a sit-in at school. The ad claimed they’d been padlocked in the school’s dining room, which was not the case. And it said Martin Luther King had been arrested seven times. He’d been arrested four. The ad was to raise money for his legal defense. Sullivan’s name never appeared, but he claimed he was defamed by inference, since the ad mistakenly referred to actions by the police, and as a commissioner he oversaw the police.

A trial court ordered the paper to pay Sullivan $500,000 and the Alabama Supreme Court upheld the ruling and the award.

“That alone threatened the ability of the Times to cover the news in Alabama, and in the weeks following it, others piled on,” Jim Newton wrote in “Justice for All,” a biography of Earl Warren, the chief justice at the time of the Sullivan case. “By the time the case had reached the United States Supreme Court, in 1964, there were eleven pending libel cases against the paper in Alabama alone, seeking a combined $5.6 million,” the equivalent of $50 million in inflation-adjusted dollars. “Few doubted who would win those cases in Alabama courtrooms. The effect on the Times was potentially devastating; while New York Times v. Sullivan was pending, the paper pulled its reporters out of Alabama, achieving precisely what the state had hoped–an end to national attention to its racial policies, at least in the pages of the Times, and a portent of diminished coverage by other national news organizations.”

Civil rights leaders, including Ralph Abernathy, had also been personally sued in the same action, placing their financial security at stake, along with their ability to carry on as leaders of the civil rights movement. “If innocent mistakes, as interpreted by hostile Southern juries, would be enough to shut down coverage, then the movement itself was in peril,” Newton wrote. “It was that threat, more than sympathy for the newspaper, that captured Warren’s interest and attention.”

The court ruled 9-0 in favor of the Times, with an opinion authored by Justice William Brennan.

The Florida appeals-court opinion came as a three-judge panel of the appeals court upheld the dismissal of a defamation lawsuit filed by former Orange Park Councilman Roland Mastandrea against Sherri Snow, a resident who he accused of making defamatory statements.

A brief filed by Snow’s attorneys indicated the statements involved a proposed real-estate development in the Clay County town. In a three-page main opinion Wednesday, the appeals court upheld a circuit judge’s decision that there was “no evidence of actual malice.” Brad Thomas, appointed to the court by Gov. Jeb Bush in 2005 and retained in elections since, concurred with the opinion because he said he was bound by the standard in New York Times v. Sullivan.

–FlaglerLive and The News Service of Florida

![]()

Click to access mastandrea-v-snow-sullivan-v-nyt.pdf

Ray W. says

Please note that Judge Thomas wrote a concurring opinion, not a dissenting opinion. He focuses on a “policy” decision made by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1964 to deal with an issue that was considered critical at the time. In the end, the significance accorded to precedence drives Judge Thomas’ to concur in the majority opinion, not to dissent from it.

I have argued several times that one of the core policies of the so-called conservative movement is to undermine the significance accorded to precedence. During recent Senate confirmation hearings on nominations to the Supreme Court, efforts were made to distinguish “super” precedence from ordinary precedence. All long as I have been following the issue, so-called conservatives have written articles, and privately argued to me, about how Marbury v. Madison was wrongly decided. If ordinary precedence, as a standard utilized during appellate review, ever goes away, then the abortion issue takes a different path, the suppression of illegally obtained confessions, admissions, and statements against interest takes a different path, the suppression of illegally seized evidence takes a different path, and 1st Amendment law, re: absence of malice, takes a different path.

Underlying the entire effort to undermine Marbury v. Madison is the “original intent” argument. Once again, I point out that our founding fathers were educated during a time now recognized as the “Age of Reason.” They intended future generations to argue everything, repeatedly, for as long as our liberal democratic Constitutional republic lasted. To them, common sense was a process, not a result. If common sense is a process, then we have to engage in that process anew each time an argument is raised. If common sense is a result, then someone else, from long ago, can decide the meaning of common sense and we are to be bound by that meaning. I am reminded of the speech given by Madison on the floor of the House of Representatives in 1796. Members were already arguing over the original intent of the founding fathers. Madison told his fellow members that, although he had written much of the Constitution, in his opinion he was not a founding father, because he had produced a “dead” document. The members of the various state ratifying conventions who voted to adopt the proposed Constitution, in Madison’s view, were the founding fathers because they were the ones who breathed life into the dead document he had produced. Using Madison’s reasoning process, Thomas Jefferson was not a founding father, because he was America’s ambassador to France during the time of both the Constitutional Convention and the various state ratifying conventions; he was not chosen to participate in the forming of the Constitution or the ratifying of it.

Snow, S says

Very good article. In addition, Florida’s Anti SLAPP statute is critical for citizens who care and want to engage in their community affairs without being threatened and silenced by those in powerful positions.

palmcoaster says

You are correct Snow and the local case of the former SOE Kim Weeks along Dennis McDonald and Mark Richter I saw it always as a FCBOCC blunt violation of the Florida Anti-Slapp https://www.floridabar.org/the-florida-bar-journal/floridas-expanded-anti-slapp-law-more-protection-for-targeted-speakers/.