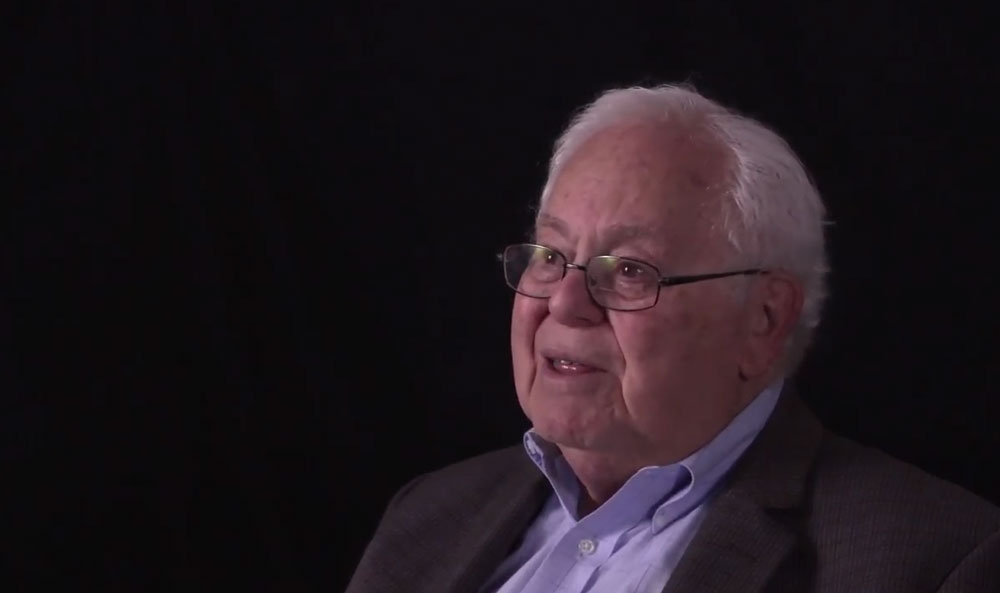

In a compelling new interview conducted by attorney and filmmaker Ted Corless, the late Florida Supreme Court Chief Justice Gerald Kogan lists the numerous reasons why he believed Florida’s death penalty should be abolished.

“I have been a member of the Florida Bar for 63 years,” Kogan said in the interview recorded shortly before his death. “I have handled capital cases for most of that period of time. I became the chief prosecutor in Miami Dade County. And what happened was, at the beginning I would tell all of the people who worked under me, you’ve got to go ahead and ask the jury to enter the death penalty in this particular case. And then I began as the years went by, I began saying, wait a minute, that’s a bad position for me to take. And I believe that the death penalty should absolutely not be a punishment delivered by the State of Florida, or for that matter, neither any place in the United States or the world.”

The video, released today on the Corless Barfeld Trial Group YouTube channel, is the first in a series of several videos featuring Floridians with direct, first person experience with the death penalty. The release is timed with the anniversary of the exoneration of the first death row survivor in the modern era in the country and in Florida. The exoneration was the first of 30 people from Florida, a number that is likely to grow. (The state has executed 99 Floridians since 1979. In essence one death row inmate has been exonerated for every three executions.)

In a particularly compelling part of the interview, Justice Kogan shares that he is convinced that innocent people have been executed in Florida. These cases haunted Kogan and, in the video, he speaks movingly of the gravity of being “the last word” before an execution.

“We are executing people who probably are innocent,” he says in the video.

“Justice Kogan was right about the risk of executing an innocent person,” said Mark Elliott, executive director of Floridians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty. “Our state has had 30 death row exonerations – the highest in the nation. That’s one exoneration for every three executions. That should shock the conscience of every Floridian.”

As a former prosecutor, Justice Kogan wasn’t always against the death penalty. Over the course of his career, he developed grave concerns about it. Critically, during his time on the Court, Justice Kogan learned that half of his and his colleagues’ hours of work would be devoted to one class of cases: people who had been condemned to death. The experience shaped his view that the death penalty is inherently unfair and would always carry the risk of executing an innocent person.

Gov. Bob Martinez appointed Kogan to the Supreme Court in January 1987. He served until 1998 and was Chief Justice starting in 1996.

Kogan died on March 4. The video series is a posthumous tribute to a man who was clearly passionate about justice. Justice Kogan believed that if Floridians were aware of this reality, they would reject the death penalty.

“When we find out that we have killed an innocent person,” Kogan says in the video, “you don’t go to the cemetery and open up the coffin and say, sorry fellow, we made a mistake, or young lady, older lady–sorry, we made a mistake. But don’t worry, your family will be able to collect money from the state of Florida. We cannot bring back to life people that we made mistakes about. And we just have to do something.”

“This video is really groundbreaking,” said Elliott. “Justice Kogan knew the justice system intimately. He was involved in more than a thousand death penalty cases. If a conservative former prosecutor that led Florida’s highest court thinks we should end the death penalty, then it’s something our current leaders should seriously consider.”

![]()

TJ Miller says

No we need to use it more often

Frank says

I agree, a death penalty that is never used in not a deterrent.

James M. Mejuto says

No ! Florida should NOT abolish the DEATH penalty !

James M. Mejuto

Pogo says

@FWIW

The late Justice Kogan had plenty of good company.

Notice anything that the countries that execute people have in common? Just saying…

https://www.google.com/search?d&q=death+penalty+by+country

“Under what circumstances is it moral for a group to do that which is not moral for a member of that group to do alone?”

― Robert A Heinlein

Trailer Bob says

I guess the natural though process would be to give people who are basically not filmed or caught in the act that privilege, as the judge speaks to those cases where he did give the death penalty to people who were found to not be guilty after the execution.

I understand how that would feel to realize you made an error in judgement that took a life.

But that still leaves a very different question when someone HAS been ABSOLUTELY found guilty of a murder. What do you tell the victims family members? How do you justify letting someone who has, let’s say, without a doubt, killed someone’s entire family, or infant child? Are we not then making a statement with our actions that the murderer is welcome to more life on this earth than the dead, murdered child, or any innocent person brutally murdered? So I guess I would disagree with the Judge on this one. Unless, there would be different, additional rationale to be considered for those who should be “transitioned” to death, those who are absolutely, without a doubt, guilty of the heinous crime of taking an innocent person’s life.

Ray W. says

Should anyone ever form credulity for the likes of TJ Miller or James M. Mejuto on this subject matter? I know they mean well, but can it ever be doubted that Justice Kogan possesses more experience, is better educated and informed, and is, perhaps, wiser than this pair, yet they immediately think Kogan is wrong. I give props to Trailer Bob. At least he gives reasons why he thinks his points are better and he considers other points of view. I don’t agree with him, perhaps because I possess more experience, am better educated and informed, and am, perhaps, wiser than he is on this limited subject matter. How many of those 30 exonerations mentioned in the article involved prosecutors, jurors and judges who believed the accused was guilty beyond all doubt?

I have written about this before. I attended a presentation at a seminar at which a victim of a violent and brutal rape exhorted the crowd of defense attorneys to continue the work they do. She was horrified that the man she pointed her finger at during a trial as her violent and brutal rapist had been exonerated by DNA evidence. Wilton Dedge spent 23 years in prison for a crime she was convinced beyond all doubt that he had committed. Only he didn’t do it.

I prosecuted a juvenile as an adult for a vicious aggravated battery and persuaded the judge to send him to prison even though he had no priors. He confessed to a detective. The victim identified him from a lineup. He stood in front of a court and entered a plea, telling a judge to punish him for the crime. Months later, a different defense attorney called me to say the defendant’s adult brother with a long criminal history, who bore close resemblance, had actually committed the crime. He had persuaded his younger brother to come forward and take responsibility for the crime, thinking he would receive a juvenile probationary sentence as a first offender. I agreed to allow the juvenile to withdraw his plea and the judge accepted the adult brother’s plea and sentenced him to an even longer prison term. I then prosecuted the juvenile as an adult for perjury to the court, but offered a county jail sentence. I still don’t know who did what, because I wasn’t there when it happened, but I hope justice was served.

My father told me of prosecuting a motel robber who received a lengthy prison term. Some time later, a detective from another jurisdiction called my father to tell him that another man had confessed to a string of motel robberies, including the one in DeLand. The robber owned a car that matched the eyewitnesses description and the robber gave details that only the robber would know. Before the next day ended, the original defendant was out of prison.

I covered first appearances one Sunday as a normal part of the rotation of prosecutors. The judge covering the process encountered a man who had been arrested on an outstanding Maryland warrant for failing to pay child support. The detainee blurted out that he had been in court in Maryland the week before and had posted the child support detainer and been released. The judge spent at least four hours chasing down officials in Maryland. He reached the judge at a country club, calling him off the golf course. The Maryland judge stated that he remembered the case and told the Volusia judge that the man had to have posted the child support detainer because he would still be in custody in Maryland if he had not. The Volusia judge commented to us all when he began the search that he would not allow an innocent man to spend one day in jail for something he didn’t do. The warrant had simply not been withdrawn by the Maryland clerk when the detainer had been posted and the man released in Maryland. I always defended that judge to any who questioned his actions (he retired long ago), as very few judges would take the time to do what he did. As a citizen, I am in his debt. People like him ensure trust in the court system. I told young prosecutors that they could do more damage to society than just about any defendant, because they had been entrusted with power and defendants had not. Abuse that power and the effects will last a long time.

This is the key to rebutting Trailer Bob’s position. If a prosecutor is a witness to a case, he or she cannot serve both as a witness and a prosecutor. If a defense attorney is a witness to a case, he or she cannot serve both as a witness and a defense attorney. If a judge is a witness to a case, he or she cannot serve both as a witness and a judge. If a juror is a witness to a case, he or she cannot serve both as a witness or a juror. The entire process of a trial, therefore, is conducted by those who were not witnesses to the case. Only in that way can a fair and impartial trial ever occur, with testimony coming from the witness stand and evidence accepted by the court into the trial record. But no one really knows what happened, because they were not witnesses to the crime. That means that jurors have to rely on witnesses and evidence to decide guilt and witnesses and evidence can be wrong. I assert that nothing can ever be as certain as Trailer Bob would have it, simply because I knew that I had to rely on other people in each and every one of my prosecutions. I learned very quickly that people would try to use me to hurt other people.

Ritchie says

Mostly the poor and/or under-privileged are exposed to suffering capital punishment.

Punishing them with death is not offensive to the rest of us.

Ray W. says

30 exonerations! That means 30 prosecutors made the decision to seek death. 30 juries (360 eligible citizens) made the decision to recommend death. 30 judges made the decision to impose death. And all 420 people were wrong, because to exonerate means to “absolve (someone) from blame for a fault or wrongdoing, especially after due consideration of the case.” Many of the exonerations have come from examination of DNA samples preserved in the case files. How can so many people make so many mistakes where one’s life is at stake? There is an old joke in the death penalty defense sector, perhaps based on truth: A prospective juror, when asked under what conditions he could impose the death penalty, replied that he could do so on Saturdays, as he would not be working. During one of my death penalty jury selection proceedings, one prospective juror responded to the judge’s question of whether she could impose a death sentence by stating that she could do so where a child or animal had been injured. She was struck from the panel for cause without objection by the State. In another selection process, 12 jurors and three alternates were chosen from 165 prospective jurors. 150 did not make the cut, including one who was so visibly disturbed that we simply stopped asking him questions after the judge told us he would individually question the juror during a break. That juror promptly lambasted the judge, stating his refusal to recognize the judge’s authority because the judge clearly spoke with an accent. To the juror, no immigrant could ever serve as a judge. Again, struck for cause without objection from the State.

To some who visit FlaglerLive, there can be no debate about the death penalty. Many of those who favor imposing the death penalty, including those who would impose death if a Chihuahua were injured, simply will not listen to those who oppose it, and vice-versa. The decision having already been made by so many people, how can it be debated? Could such a person ever perform as a fair and impartial juror?

For those who remain open to the death penalty debate, there are many facets, each carrying weight, each having a strong measure of validity. For me, the debate began at an early age. My oldest brother, Robert, brought Tolkien’s Hobbit home from prep school when I was 10. I avidly read it non-stop and then re-read it. The next summer, in 1968, he brought the Lord of the Rings for me to read. which I consumed in less than a week, then re-read it. One passage in particular caught my attention. Frodo, spotting Gollum tracking the Fellowship of the Ring, expressed his belief to Gandalf that it was a pity that Bilbo had not killed Gollum when he had the chance. Gandalf answered that it was pity that stayed Bilbo’s sword hand, stating: “Many that die deserve life, and some that live deserve death. Can you give it to them, Frodo? Do not be too eager to deal out death in judgment. Even the wise cannot see all ends. My heart tells me that Gollum has some part to play, for good or ill, before this is all over. The pity of Bilbo may rule the fate of many.” To my 11-year-old mind, this exchange posed many questions.

Just before this timeframe, my father successfully prosecuted Charles Cirack for the 1965 murder of Moses Jackson. For the first time since Reconstruction, an all-white southern jury recommended the death penalty for Cirack, a white man, for killing Jackson, a black man. In other words, roughly 90 years had passed in the South without any death penalty recommendations by white jurors against white defendants for murdering black people. While I really cannot remember a time when I did not know small facets of the Cirack case, I cannot say my father talked about it over the dinner table when I was eight years old. Since I was a paperboy beginning in early 1967, I began to read the paper every day, so I have to believe that I read about the Cirack case, or at least the appeal, in the paper. I do recall my father repeatedly telling me that during jury deliberations, he was in the bathroom throwing up. My father expressed to me his distaste for the death penalty, though he said he had been elected to impose it, so he followed the law and imposed it when he thought necessary. It just turned out that he was the only southern prosecutor in 90 years who thought it necessary to seek it against a white man for killing a black man and succeeded at it. He also stated he was relieved when the death penalty was abolished in 1972, in the Furman v. Georgia decision, which struck down the death penalty because it had repeatedly been imposed in an arbitrary and capricious manner. Prosecutors had simply and repeatedly proved to the Court that they were unable to seek death in an unbiased way. It wasn’t that white people weren’t killing black people in the South during those years; they simply weren’t sentenced to death for during so, with one exception. Cirack died in prison.

From a different perspective, my family still possesses a 1969 News-Journal article about my father’s lead pilot, John Knox. In October, 1944, Knox flew Ragadas to Italy with his crew. He flew his first combat mission in a co-pilot’s seat with an experienced crew before he was slated to lead his own crew into combat. Shot down, he was one of seven captured by an SS detachment; all were executed in a field. The other three survivors were captured by the Wermacht and sent to a POW camp. After the war, the SS officer was tried by a war crimes tribunal and executed. I never heard my father disapprove of that outcome. I have often wondered what would have happened had Hitler survived the war and been sentenced to prison. Would Hitler have inspired a resistance movement from his cell? If so, how many Allied soldiers would have died during the occupation of Germany as a result of Hitler’s inspiration? No one will ever know the answer, but is the death penalty more appropriate in a war crimes setting under military law, as opposed to a state-sanctioned criminal law setting under a civilian government? To those who oppose the death penalty, should it be applied only in war crimes settings?

Federal legislation requires prosecution teams to deliberate when considering whether to file notice of intent to impose the death penalty, with an additional requirement that the defense team be given an opportunity to present mitigation evidence to the team prior to the deliberative process. Florida requires no similar opportunity, though I have participated in such efforts over the years in an informal process, for which access I still give thanks, because the prosecutors were not required to allow me to provide such evidence before the decision was made. Good luck to any who attempt to persuade Florida’s legislature to add such a requirement to the death penalty process. You just haven’t lived until you have watched a so-called conservative legislator break down sobbing as he debates how to reform the death penalty statute after it had been struck down as unconstitutional; he apparently could not believe he had to change the old law. The possibility that someone, anyone, might not be sentenced to death under the new scheme was just too much for him.

For me, I accept Tolkien’s premise that even the wise cannot see all ends. When openings in the death penalty unit were made known to me, I chose not to apply for the position. I am not stating that I would have been selected had I applied, for I will never know that answer. I am stating that I knew enough to know that very few people possess the requisite training, experience and wisdom to determine who should live or die and even fewer of them work in the State Attorney’s Office. In those days, I knew every one of the prosecutors who made such decisions and I would not entrust very many of them with that power. A few years later, when defending a death penalty case, a judge called a prosecutor to the bench. When asked whether this was really a death penalty case, the prosecutor answered that it was not, but the “idiots” upstairs had ordered him to seek the death penalty and he was a good soldier. Within a few weeks, he resigned his position and went into private practice. Another time, I learned that my client’s mother had tried to hire John Tanner shortly before he was elected a second time as State Attorney. She stated in deposition that she had told Mr. Tanner everything her son had told her about the event. I filed a motion to disqualify the entire office from the case, alleging that Mr. Tanner was disqualified by that contact. The prosecutor, in a vain effort to save the day, told the trial judge that he had not only not talked with Mr. Tanner about that case, he had not talked with Mr. Tanner about any of his death penalty cases. This was about six months after Mr. Tanner had taken office. I asked the prosecutor if he was telling the judge that Mr. Tanner had delegated the power to determine who lived or died to his assistants? The judge ordered the entire office off the case. About two months later, I received a call from a South Florida prosecutor who had been appointed by the governor to take over the case. She introduced herself and asked me whether the Volusia prosecutors really thought this was a death penalty case? At her first court appearance, she told the judge she would be filing a document withdrawing the notice of intent to seek death. I won the case without even having to talk to the new prosecutor, as she simply could not believe anyone would seek death under those facts. As I recall, the defendant eventually pled to a 17 year sentence. No one is wise enough to see all ends, except those who have already made up their minds.

As an aside, one of the more surprising facts that I came across while researching death penalty issues many years ago was a CDC mortality chart that reflected a life expectancy for black males in 1900 at 33 years, while white males were expected to live 47 years if born in 1900. As I recall, only 29 of the 45 states were sending mortality data at that time to what is now the CDC and I don’t know if southern states were included in the calculations, but white males lived just over 40% longer than black males when born in 1900. Some of that difference had to include murders of black males as well as a lack of medical care. I know that some will say that reflects black-on-black crime, but I suspect it would be extraordinarily difficult for any poster on this site to win an argument that white on black crime did not impact the life expectancy of black males born in America in 1900.

deb says

Nope keep it as it is. When someone brutally kills someone and is also a repeat offender that has been let out of prison for ” good behavior”,, I say give him a good gassing or better yet a hanging.