By Robert Gudmestad

Hank Greenberg might be the best baseball player you’ve never heard of.

Greenberg was the first baseman for the Detroit Tigers during the 1930s and 1940s. His career was relatively short – 13 years – and interrupted by two stints of service in World War II.

Yet outside the war years, there were glorious seasons.

Greenberg led the American League in home runs four times, played in five All-Star Games, twice won the American League’s Most Valuable Player Award and, in 1938, nearly broke what was then the game’s most hallowed record: Babe Ruth’s 60 home runs in one season. In 1956, Greenberg was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Greenberg was also Jewish, and he is often called America’s first Jewish sports superstar. As Greenberg wrote in his autobiography, that was not an easy honor to bear. Greenberg played during a time of rising antisemitism, and the cruel taunts he suffered from players and fans lasted throughout his career. Vile remarks and bigoted slurs – “kike,” “sheenie” and “Jew bastard” were typical – left a mark on him and the sport he loved.

Along the way, Greenberg also faced a crisis of conscience: his struggle on whether to play during Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, the Jewish High Holidays. He resolved the conflict with a Solomon-like choice, more than 30 years before baseball legend Sandy Koufax pondered the same dilemma during the 1965 World Series.

Today, nearly 80 years after Greenberg retired from baseball, antisemitism is once again on the rise both in the U.S. and worldwide. As a historian of American sport, I suggest there are lessons to be learned on how Greenberg handled the hate.

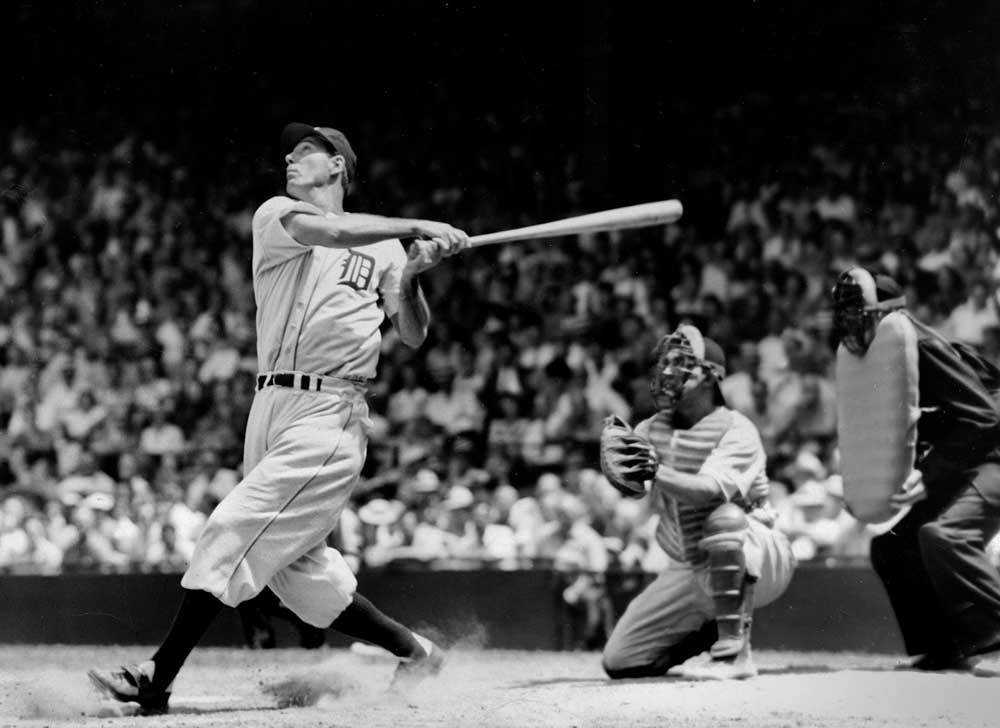

Bettmann via Getty Images

Horns like the devil

Greenberg signed a contract with the Tigers in 1930 and played in the minor leagues for the next three years. For many of his teammates, he was the first Jewish person they’d ever met. One told Greenberg, quite seriously, that he thought Jewish people had horns, like the devil.

Once brought up to the major leagues, Greenberg was generally accepted by his teammates. The same could not be said of opposing players and fans, who hounded him throughout his career. The fans insulting Greenberg were in the distinct minority, but they were loud, nonstop and got virtually no resistance from other fans or the media.

Greenberg’s response to the abuse: ignore it. But he reacted at least once, during a game against the Chicago White Sox. One Chicago player tried to injure Greenberg – his autobiography does not report how – and another called him a “yellow Jew son of a bitch.” After the game, Greenberg visited the opposing team’s locker room and demanded to know who the name caller was. At 6 feet, 3 inches tall and 200-plus pounds, Greenberg was intimidating. The room fell silent. The White Sox players never antagonized him again.

Other pressures bore down on Greenberg. Detroit was a hotbed of antisemitism in the 1930s. The Dearborn Independent, a newspaper owned by the industrialist Henry Ford, described Jews as “the world’s foremost problem,” an echo of Ford’s antisemitic beliefs. The city was also home to Father Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest who reviled Jews and spread antisemitic rhetoric during his radio show – which at its height was heard by perhaps 40 million people. Overseas, Adolf Hitler was the fuhrer of Germany, and his persecution of Jews became even more apparent after Kristallnacht, in November 1938, when the Nazi regime went on an antisemitic rampage.

“I came to feel,” Greenberg wrote later, “that if I, as a Jew, hit a home run, I was hitting one against Hitler.”

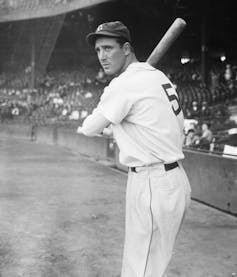

Bettmann via Getty Images

Playing on Jewish holidays

In 1934, when he was 23, Greenberg decided he would not play on the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah, a holiday when observant Jews were supposed to pray and not work. But the Tigers were in a close race for the American League pennant. The team needed Greenberg, their star player.

A local newspaper reporter interviewed a Detroit rabbi and asked if it was acceptable for Greenberg to play. The rabbi said it was OK. Deciding at the last minute, Greenberg played and hit two home runs. Detroit won the game, 2-1. The Detroit Free Press ran a headline in Yiddish, with an English translation: “Happy New Year, Hank.”

Ten days later came Yom Kippur, the most sacred of all Jewish holidays. Also known as the Day of Atonement, observant Jews are to spend the day in prayer and self-reflection; baseball was not on the agenda. This time, Greenberg did not play, and attended services instead. When he entered the synagogue, the congregation applauded.

The Tigers lost 5-2 to the New York Yankees that day. But Detroit won the pennant anyway.

“I used to resent being singled out as a Jewish ballplayer, period,” Greenberg said in his autobiography. “I’m not sure why or when it changed, because I’m still not a particularly religious person. Lately, though, I find myself wanting to be remembered not only as a great ballplayer, but even more as a great Jewish ballplayer.”

Meeting Robinson

1947 was Jackie Robinson’s rookie year and Greenberg’s last. Robinson, the first baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers, had broken the color line and was baseball’s first Black player of the modern era; he was enduring enormous abuse, something Greenberg, now with the Pittsburgh Pirates, clearly understood. They played against each other for the first time at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh in May.

Bruce Bennett via Getty Images

In the fourth inning, Greenberg got to first on a walk, and according to newspaper accounts, he had a few words for Robinson: “I know it’s plenty tough,” he said. “You’re a good ballplayer, and you’ll do all right.”

Greenberg also publicly supported Robinson, one of the few opposing players to do so.

Nearly a half-century later, Supreme Court justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer were considering whether the Supreme Court should meet on Yom Kippur. They too found inspiration from Greenberg; Ginsburg noted that Greenberg did not “betray his conscience.” The Supreme Court did not meet on Yom Kippur that year, and it hasn’t since.

Although there has been tremendous progress, racial and ethnic slurs persist in American sports. In 2024, some fans directed racially abusive comments at two Black players on the U.S. men’s national soccer team. In English football – known as soccer in the U.S. – Muslim players reported widespread discrimination and abuse. Things have changed, but not enough.

Although not a devout Jew, Greenberg understood that to endure the abuse, he had to embrace his identity. Those athletes of today, recently stung by the vitriol of bigots and trolls, may wish to take heed of the lessons learned by this reticent hero from the previous century, a man whose quiet dignity spoke volumes.

![]()

Robert Gudmestad is Professor and Chair of the History Department at Colorado State University.

Leave a Reply