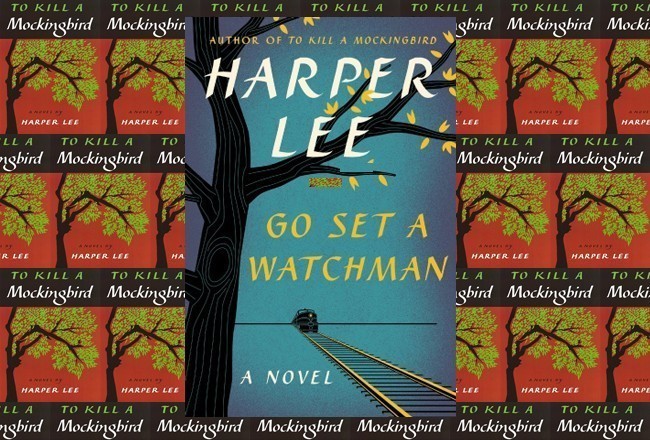

Welcome to part five of FlaglerLive’s live-blogging of “Go Set a Watchman.” We’ve invited 10 people of varied backgrounds from around the community to read the book and write their response to each of its 19 chapters, from whatever perspective they choose, at whatever length they choose, in 19 installments over the next few weeks. For a few more details on the project, read the introduction here. As always, we start with a summary of the chapter at hand and dive right into the critics’ responses.

![]()

Our Ten Critics: Quick Links

- Today’s Chapter Summary

- Darrell Smitty Smith

- Jay Livingston

- Inna Hardison

- Daniel Masbad

- Bill McGuire

- Brian McMillan

- Mary Ann Clark

- Jon Hardison

- Monica Campana

- Pierre Tristam

![]()

Chapter 5 summary: The longest chapter so far, its 30 pages span present, past and a great deal of imagination in the arc of Jean Louise’s drive to Finch Landing with Henry. She remembers her time with Jem and Dill in a flashback filled with the children’s recreation of scenes starring Tom Swift, Tarzan, preachers, revivals and baptisms. Back to the present Henry and Jean Louise arrive at Finch’s Landing, the old patriarchal property that, unbeknownst to Scout, was sold just a few months before. Scout is upset for not having been told, and for losing the one place in Maycomb County she’d have willingly lived. There is a bit of courtship. Henry asks her about marriage without actually asking her. She proposes he could make her an offer. Instead, they dive into the water, their clothes mostly still on. On the way home a “Carload of Negores,” as Henry puts it, passes by them. A hint of Henry’s prejudice peeks out. At home, there’s no sign of Atticus. Jean Louise picks out a book from her father’s library and falls asleep three pages in, her light still on.

Darrell Smitty Smith, Flagler Beach AC technician, FlaglerLive contributor and George Carlin reincarnation: So after completing Chapter 4 and thinking about how I should be shocked and disgusted by Jean Louise un-PC comments on Male/Female relationships today, but actually agreed with much of them (at least as far as the dichotomy of what women say they want versus what they actually are attracted to), it made me think of the differences between the accepted Common Wisdoms of our world today versus the bedrock beliefs of the 1950’s. And then we get to Chapter 5 and a flashback to Scout and her friends playing a game in the backyard where they were pretending to be adventurers traveling to Deepest, Darkest Africa to rescue a Doctor/Explorer based on the Stanley and Livingston story that was so popular for years when I was growing up. While somewhat clunky in its telling, it is wonderfully innocent in its own way. It got me thinking about how different things have become. Not to get all maudlin about it, but the Times Have Changed So.

Darrell Smitty Smith, Flagler Beach AC technician, FlaglerLive contributor and George Carlin reincarnation: So after completing Chapter 4 and thinking about how I should be shocked and disgusted by Jean Louise un-PC comments on Male/Female relationships today, but actually agreed with much of them (at least as far as the dichotomy of what women say they want versus what they actually are attracted to), it made me think of the differences between the accepted Common Wisdoms of our world today versus the bedrock beliefs of the 1950’s. And then we get to Chapter 5 and a flashback to Scout and her friends playing a game in the backyard where they were pretending to be adventurers traveling to Deepest, Darkest Africa to rescue a Doctor/Explorer based on the Stanley and Livingston story that was so popular for years when I was growing up. While somewhat clunky in its telling, it is wonderfully innocent in its own way. It got me thinking about how different things have become. Not to get all maudlin about it, but the Times Have Changed So.

Today, 12-year-old kids are united in one fierce debate across our entire land. It concerns the epic Twitter battle between Taylor Swifts’ seeming disrespect shown towards fellow entertainer Nikki Minaj regarding her song Anaconda, a heart-felt homage to the value of ginormous penises in today’s society. Complete with the trademarked Minaj’ fluttering Glutius Max that is beautifully reminiscent of various ancient avian mating rituals. And it is getting deeper and more serious now that the debate has been joined by another important celebrity named Katy Perry, who’s evident claim to fame is having the face of a 14 year old gifted or implanted with enormous breasts that Mae West could have only dreamed about. Oh, and a squeaky little girl voice plus the best publicists in the world. See for yourself. Which makes me come to the obvious conclusion that we have as much business critiquing this dated book today as an Australian Aborigine has reviewing Nanook of the North. For your viewing and listening pleasure:

Jay Livingston, attorney with Livingston & Sword in Palm Coast: [To come.]

Jay Livingston, attorney with Livingston & Sword in Palm Coast: [To come.]

Inna Hardison, co-owner of Ha Media and former publisher of Palm Coast Lifestyles magazine:I am not exactly sure how to tackle this one, so forgive the disjointed ramblings, if you will.

Inna Hardison, co-owner of Ha Media and former publisher of Palm Coast Lifestyles magazine:I am not exactly sure how to tackle this one, so forgive the disjointed ramblings, if you will.

For the first time, I think, I saw a glimpse of what Lee’s first publisher must have seen, a lovely ability to delve into the minds and hearts of children. The childhood flashbacks here are the closest I’ve come so far to feeling like I was actually reading a book by the same author, albeit much improved in Mockingbird even in that. There are still too many attempts at being clever, too many words wasted, and yet reading about their escapades was not only palatable, but at times, enjoyable.

Of course that might have more to do with how I’d spent most of my summers, immersed in the various re-enactments of whatever adventure we’d read at the time. The books were different, but not much beyond that. It all brought a flood of memories of Indian war paint on our filthy faces (James Fenimore Cooper era), hand-made willow bows in our hands and the many holes we probably made in the sun-scorched exposed tar of our neighbors’ roofs. It’s bizarre and magical to me that our experiences in that sense were so similar, considering the drastically different geographies, decades and even the landscapes, but I suppose if there is anything that can still induce me into feeling optimistic about the state of this sorry-assed world nowadays, it’s that one tiny hope that we are not all so different after all.

In any case, the entirety of Scout’s daydream on the ride to the landing felt like a much needed respite from the awkward and the stilted that preceded it. It was lovely, and then Lee had to go on and ruin it for me again with Jean Louise back to her adult half-horny half-frigid self. “I’d have to wear a hat. I’d drop the babies and kill’em,” says our grown up Scout with a civil servant’s detachment, and a little bit of me dies with it. A “giant black bee” of negroes didn’t even sting much after that.

I went to sleep with my old tattered copy of Mockingbird, just to get the bitter taste out of my mouth, and if anything, I’m grateful for that. It’s been far too many years since I’ve read that book, and with every line of fresh, blunt, un-stilted dialogue, every succinct and utterly apt description and all the words brilliantly left off those old pages, it became clearer and clearer that these two books were not written by the same hand. Nobody grows up that much in a span of a couple of years, whether as a writer or a human, and while I can generally forgive most atrocious flaws in writing when dealing with what is ostensibly a draft of a young author, it’s the flaws in basic humanity that are most jarring to my sensibilities.

This whole exercise is starting to feel dirty, indecent. Like hunting on a Sunday or waking up mermaids.

Daniel Masbad, 2015 high school graduate (home-schooled) and concertmaster of the Flagler Youth Orchestra: [To Come.]

Daniel Masbad, 2015 high school graduate (home-schooled) and concertmaster of the Flagler Youth Orchestra: [To Come.]

Bill McGuire, Palm Coast City Councilman and management consultant: I had high hopes after chapter 4 that this book would pull out of its doldrums, the plot would start materializing and moving forward and the characters would become more interesting. Chapter 5, however, has shifted downward into a stifling and totally boring story. I’m trying to like this book, really I am-everybody says it’s a classic. I remember asking my high school English composition teacher to define a classic work of literature for me. He smiled and said, “a classic is a book that everyone wants to have read and no one wants to read.” And, aspiring to be a well-read individual, I have always essayed to read an occasional work of classical literature or poetry, mixed in with my novels that comprise the bulk of my reading. Once again, I digress. Chapter 5. reminds me of soap operas that run year after year in that nothing ever seems to happen, conversations are boring up until the end of the program when, all of a sudden, the organ music rises in crescendo and statements are made which imply that something exciting is going to happen in the next episode. You could film an entire episode in one room with a small group of people with whom the viewers are expected to form the kind of emotional attachment that will guarantee that you come back to the soap opera week after week, if not year after year.

Bill McGuire, Palm Coast City Councilman and management consultant: I had high hopes after chapter 4 that this book would pull out of its doldrums, the plot would start materializing and moving forward and the characters would become more interesting. Chapter 5, however, has shifted downward into a stifling and totally boring story. I’m trying to like this book, really I am-everybody says it’s a classic. I remember asking my high school English composition teacher to define a classic work of literature for me. He smiled and said, “a classic is a book that everyone wants to have read and no one wants to read.” And, aspiring to be a well-read individual, I have always essayed to read an occasional work of classical literature or poetry, mixed in with my novels that comprise the bulk of my reading. Once again, I digress. Chapter 5. reminds me of soap operas that run year after year in that nothing ever seems to happen, conversations are boring up until the end of the program when, all of a sudden, the organ music rises in crescendo and statements are made which imply that something exciting is going to happen in the next episode. You could film an entire episode in one room with a small group of people with whom the viewers are expected to form the kind of emotional attachment that will guarantee that you come back to the soap opera week after week, if not year after year.

Henry and Louise are out on a date, driving along in Henry’s car making small talk and reminiscing about many things that happened in their youth. Playing games outdoors – mostly make believe games based upon popular characters in their youth, such as Tom Swift. The character of Dill is introduced. He appears to be a childhood playmate of no particular import. Other games of make-believe were played and a popular one was to mimic the local religious services, along with the incumbent ritual which is little changed today. A decision is made to baptize Jean Louise. This involves her shedding her overalls and renders her naked, although at this age no impropriety is contemplated. Having been dunked in a slimy pond by the ersatz minister, Jean Louise is discovered in the altogether by the local minister, accompanied by Atticus. We are introduced to Calpurnia, a black domestic and long time employee of the Finch family, who scrubs Jean Louise and helps her dress. The minister’s frustration becomes hilarious to Atticus, who must excuse himself and repair to the front porch, where he gives vent to uncontrollable laughter.

Henry and Jean Louise, having come out of their daydream, arrive at Finch’s Landing, a former holding no longer in the family. After more nondescript conversation, Henry announces his goal of marrying Jean Louis, whose reaction is lukewarm, at best. In a fit of spontaneity, Henry throws Jean Louise into the river and joins her. Although both are fully clothed, the harmless prank is blown up in town the next day, a Sunday, and falsely portrayed as a naked scandal. Needless to say, Aunt Alexandra’s piety is wounded before her small band of local socialites. Henry and Jean Louise find a sardonic humor and chapter five ends.

Well, there you have it – 35 pages of “Days of our Lives.” Like sand through the hourglass this “Novel” continues to stupefy.

Brian McMillan, columnist and executive editor of the Palm Coast Observer:Chapter five is the longest yet, and it feels even longer because of an extended flashback to a time when Scout was playing make-believe with Jem and Dill. This is certainly the seed of what we find with the kids playing in “Mockingbird.”

Brian McMillan, columnist and executive editor of the Palm Coast Observer:Chapter five is the longest yet, and it feels even longer because of an extended flashback to a time when Scout was playing make-believe with Jem and Dill. This is certainly the seed of what we find with the kids playing in “Mockingbird.”

It makes me wonder what Harper Lee’s relationship was to “Watchman” as she wrote “Mockingbird.” Did she find it liberating to focus solely on Scout as a kid? Was it difficult for her to completely cut out the love story between Jean Louise and Henry? Given the length of the flashback in this chapter, it seems that Lee couldn’t help herself but have fun with those kids.

I was happy to read Pierre’s chapter four commentary, showing how certain phrases from “Watchman” were repeated, and improved upon, in “Mockingbird.” As I mentioned in my chapter four post, I feel that so far viewing “Watchman” as a stepping stone to “Mockingbird” is the most productive way to read it.

I am curious about how race continues to play a role in this story. So far, it’s not much of a factor thematically. In fact, there are signs of racism in the characters, including in Jean Louise and Henry. They discuss the “carload of Negroes” at the end of their date in a condescending and troubling way.

There are two ways to read that, and both are fascinating. First, given the progressive nature of “Mockingbird,” we could say that Harper Lee’s understanding of race matured from the time when she wrote “Watchman” to when she wrote “Mockingbird” — or at least that she was braver and skillful enough to manage a racially progressive tone in “Mockingbird,” whereas she couldn’t or wouldn’t in “Watchman.” Is it possible that something happened in Lee’s life in between the drafts that helped her see that race was what she wanted to write about, rather than writing a love story?

The second interesting way to read it is that Jean Louise and Atticus, who show hints of racism in “Watchman,” have somehow taken a turn for the worse in their attitude toward race, as compared with their progressive attitudes two decades earlier in the prequel, “Mockingbird.”

Mary Ann Clark, founder of Flagler Reads Together and president of the Flagler County Historical Society: In contrast to the lack of action in yesterday’s assignment, today’s chapter is a whirlwind of activity. Jean Louise and Henry go out on the town, have a drink and visit old haunts. She remembers family history and reunions and fun times; he thinks about being a small-town lawyer.

Mary Ann Clark, founder of Flagler Reads Together and president of the Flagler County Historical Society: In contrast to the lack of action in yesterday’s assignment, today’s chapter is a whirlwind of activity. Jean Louise and Henry go out on the town, have a drink and visit old haunts. She remembers family history and reunions and fun times; he thinks about being a small-town lawyer.

Why does Henry want to be married when he can’t at this moment support her and Aunt Alexandra doesn’t approve of him?

Do today’s kids play the “let’s pretend” games Jem, Dill and Jean Louise did? How could a video game be more fun than imagining oneself as Tarzan or Tom Swift? The revival and baptism in the pond and its after effects is a great story.

Jean Louise’s surprise at the mention of the carload of Negroes is interesting since this is 1960.

Jon Hardison, co-owner of Ha Media in Palm Coast and member of the FlaglerLive board of directors: As self involved as I probably sound in this process by now, I find I’m entirely ill equipped to evaluate any part of this work. As I’ve probably stated before, I’m not much of a reader. I pick through pages for a thing – a scrap I need in a moment. I don’t know if it’s my contempt for sitting still (I don’t even like going to the movies), or my lack of confidence that the happenings in any book could be more interested or deserving of my attention than anything going on right outside my front door, but there it is.

Jon Hardison, co-owner of Ha Media in Palm Coast and member of the FlaglerLive board of directors: As self involved as I probably sound in this process by now, I find I’m entirely ill equipped to evaluate any part of this work. As I’ve probably stated before, I’m not much of a reader. I pick through pages for a thing – a scrap I need in a moment. I don’t know if it’s my contempt for sitting still (I don’t even like going to the movies), or my lack of confidence that the happenings in any book could be more interested or deserving of my attention than anything going on right outside my front door, but there it is.

This chapter is the closest we’ve managed to come to the Lee we know and love, but my wife, cruel as ever, took it upon herself to crack open the old standard and read aloud from pages deserving of all their accolades, revealing a truth I suspect no one wants to utter, and I certainly won’t be among the first.

Surprisingly pleasant – an effortless flashback brought on by by Hank and Scout’s return to (and trespass on) what was once Finch’s Landing. The recollections reveal such sticking differences in how people of different backgrounds see the world and why. Reading Scout’s remembrances of Finch Landing’s past and how connected she was to everything was, for a city boy whose location was dictated by little more than the end of a lease agreement, jarring. The idea that Scout could recall years past and even the coming and goings of distant cousins in the tree line surrounding a clearing her family no longer owned is baffling to me. But more incredible is the fact that she didn’t know the land had been sold and didn’t seem to care much.

I could mutter on in the minor details but it’s probably more important to simply say that this is the first time I’ve cared to read on. This chapter contains many of the same little flaws and contradictions as previous chapters, but makes them far easier to overlook.

Monica Campana, just-retired head librarian at Indian Trails Middle School and free-speech advocate: This must be the chapter that inspired the editor at Harper Collins to say, “Tell it through the eyes of the children—there’s your story.” Lee’s writing flows when Jean Louise reminisces about an idyllic summer day. She makes you long for those days when imaginations ran wild sans Internet, kids entertained themselves with stories from books and life-long friendships were forged and broken. Truman Capote makes an appearance as Dill and is whiny and witty, as you would expect from the Holy Ghost himself. (Dill strips a sheet from Aunt Rachel’s bed, cuts holes in it—classic last minute Halloween costume—and makes an appearance pond-side as preacher Jem baptizes Scout.) Then we are back in the car with Henry and Jean Louise and the writing turns stilted again. Lee must have been an adult uncomfortable in her own skin—she sure as hell can’t write about it. She lived most of her life as a recluse and never seemed to fall in love with the world enough to want to make it better. Disappointing and sad.

Monica Campana, just-retired head librarian at Indian Trails Middle School and free-speech advocate: This must be the chapter that inspired the editor at Harper Collins to say, “Tell it through the eyes of the children—there’s your story.” Lee’s writing flows when Jean Louise reminisces about an idyllic summer day. She makes you long for those days when imaginations ran wild sans Internet, kids entertained themselves with stories from books and life-long friendships were forged and broken. Truman Capote makes an appearance as Dill and is whiny and witty, as you would expect from the Holy Ghost himself. (Dill strips a sheet from Aunt Rachel’s bed, cuts holes in it—classic last minute Halloween costume—and makes an appearance pond-side as preacher Jem baptizes Scout.) Then we are back in the car with Henry and Jean Louise and the writing turns stilted again. Lee must have been an adult uncomfortable in her own skin—she sure as hell can’t write about it. She lived most of her life as a recluse and never seemed to fall in love with the world enough to want to make it better. Disappointing and sad.

Pierre Tristam, editor of FlaglerLive: This long chapter is also what much of Watchman must have been like when it first thudded on the editor’s desk: flashbacks of Scout’s childhood mixed in with her present angst. This flashback didn’t make the cut in “Mockingbird,” probably because it skirts too closely to a theme that had already migrated into the better book: early in Mockingbird we are treated to the children putting on plays for themselves, particularly a play starring Boo Radley. The story had a point, as the flashback in this chapter seems not to: Atticus intervenes and delivers one of his earnest sermons. Here only the present intervenes, after a few pleasant passages that included a few choice descriptions (“Hell was and would always be as far as she was concerned, a lake of fire exactly the size of Maycomb, Alabama, surrounded by a brick wall two hundred feet high.”) The scene drags unnecessarily though until young Scout’s funny baptism. I thought the scene where she takes off her clothes in preparation for being dunked by Jem was a set-up for her latter-day skinny-dipping with Henry, but when it came to that, the two of them kept their clothes on, suggesting that she was much freer as a child than as the adult she’d become–freer with herself, her body, and her state of mind. Scout sounds increasingly like a prisoner in her own body and possibly a past she has not come to terms with. She cannot decide if she misses it or if she wants to get past it, just as she cannot decide whether she wants back in Maycomb or back in New York. It’s an interesting character study, but it’s not quite convincing. There’s no there there. There’s more of a self-absorbed woman who thinks all Maycomb is her stage, while Henry remains more or less the cardboard cut-out he’s been from the start. Toward the end of the chapter, on the lovers’ drive home, they’re passed by that “carload of Negroes,” in Henry’s indelicate words–you load animals, barrels and manure, of course, to which he’s comparing those negroes, otherwise he’d have said a carful and perhaps dropped the negroes), a hint at the bigot to come, and, I was tempted to say, at Harper Lee’s deft touch, until I realized how she’d made Jean Louise describe the car: as “a giant black bee.” I’m guessing for her sake that Harper Lee was trying to be literary without knowing how disgusting either she was being or she was making out Scout to be.

Pierre Tristam, editor of FlaglerLive: This long chapter is also what much of Watchman must have been like when it first thudded on the editor’s desk: flashbacks of Scout’s childhood mixed in with her present angst. This flashback didn’t make the cut in “Mockingbird,” probably because it skirts too closely to a theme that had already migrated into the better book: early in Mockingbird we are treated to the children putting on plays for themselves, particularly a play starring Boo Radley. The story had a point, as the flashback in this chapter seems not to: Atticus intervenes and delivers one of his earnest sermons. Here only the present intervenes, after a few pleasant passages that included a few choice descriptions (“Hell was and would always be as far as she was concerned, a lake of fire exactly the size of Maycomb, Alabama, surrounded by a brick wall two hundred feet high.”) The scene drags unnecessarily though until young Scout’s funny baptism. I thought the scene where she takes off her clothes in preparation for being dunked by Jem was a set-up for her latter-day skinny-dipping with Henry, but when it came to that, the two of them kept their clothes on, suggesting that she was much freer as a child than as the adult she’d become–freer with herself, her body, and her state of mind. Scout sounds increasingly like a prisoner in her own body and possibly a past she has not come to terms with. She cannot decide if she misses it or if she wants to get past it, just as she cannot decide whether she wants back in Maycomb or back in New York. It’s an interesting character study, but it’s not quite convincing. There’s no there there. There’s more of a self-absorbed woman who thinks all Maycomb is her stage, while Henry remains more or less the cardboard cut-out he’s been from the start. Toward the end of the chapter, on the lovers’ drive home, they’re passed by that “carload of Negroes,” in Henry’s indelicate words–you load animals, barrels and manure, of course, to which he’s comparing those negroes, otherwise he’d have said a carful and perhaps dropped the negroes), a hint at the bigot to come, and, I was tempted to say, at Harper Lee’s deft touch, until I realized how she’d made Jean Louise describe the car: as “a giant black bee.” I’m guessing for her sake that Harper Lee was trying to be literary without knowing how disgusting either she was being or she was making out Scout to be.

Leave a Reply