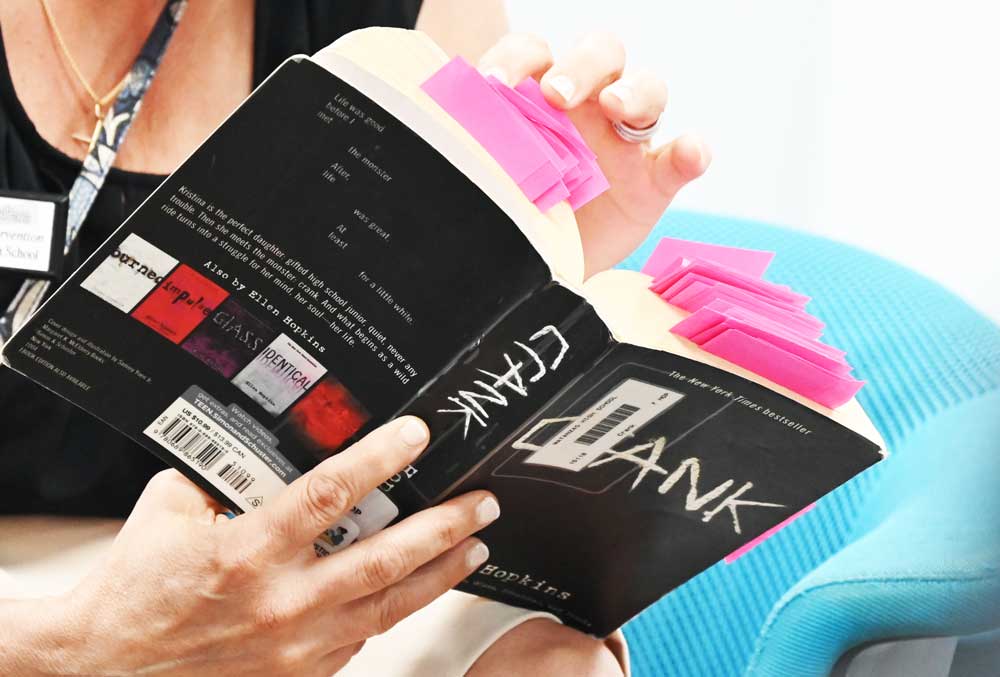

Two committees meeting jointly to review a challenge to Ellen Hopkins’s Crank, a novel tracing the spiral of a 17-year-old high school girl into drug addiction, voted unanimously Monday afternoon to keep the book on high school library shelves. But the superintendent’s recent decision to ban a book despite three unanimous votes to keep it left a chill in the committees’ decisions on Monday.

The Matanzas High School committee voted 5-0 and the Flagler Palm Coast High School committee voted 4-0 for retention, with the caveat that the books should include resources for those who may seek help for themselves or others. The book, originally published in 2004, does not include such resources.

The committee members cited the book’s value as a cautionary tale, its accessibility and readability, its topicality at a time when opioid overdoses are the leading cause of preventable, injury-related death in the United States, and its recurring depiction of drug use as a demolition of one’s person not worth the highs. (See: “Challenged in Flagler Schools: Ellen Hopkins’s Crank, a Review and a Recommendation.”

“If our goal is society is a rising tide that lifts all boats and that includes addicts, we shouldn’t be pushing people down if they made a bad decision,” one of the committee members said. “We should be trying to save lives and protect lives and stories like this try and stem that addiction before you can get started.”

One committee member noted te irony of a school board on the verge of approving the stocking of Narcan, the overdose-neutralizing agent, on school campuses while potentially entertaining the ba of a book whose aim is to keep young people from getting to the point of risking overdoses.

“And when you look at other characters that she’s meeting,” a media specialist said, referring to Kristina, the central character, “they’re not all scumbags that end up in jail, like her friend’s sister is a cheerleader. And they’re saying, Oh, well, this is the only way that I can get through my academics and my extracurriculars and everything. I’ve met students like that who have told me after they’ve graduated: Oh, you didn’t know it, but this is what I was doing during that time. The first time I heard that it was so eye opening to me because it’s not the kid you expect. It’s not the kid that quote unquote, looks like they’re on drugs. Sometimes some of our top level students are struggling with addiction.”

“Well, they’re struggling to live up to expert expectations that have been placed on them,” another committee member said, “because there’s a huge lack of mental health for them to learn how to deal with anxiety, with stress. And it’s across the board, not just with the school system, but they’re they’re desperate. It’s like, you can’t have 100 hours community service. This person actually has 200. I’ve got to get more. I’ve got to stay up later and study.”

The joint committees spent 80 minutes discussing the book before taking their votes, addressing challenged pages page by page then discussing the book’s purpose as a whole, in the context of the challenge. While it was clear from early in the discussion that committee members were not finding passages that rose to the legal definition, in law–as projected on an overhead screen–of material damaging to minors, they still addressed the challenge and justified their findings in detail. And when on occasion a committee member would get frustrated with the seeming inanity of a page denoted for objectionable material, the member leading the meeting, an assistant principal at FPC, would coax the committee member back onto the task.

“I keep on struggling, even though I’ve been in several of these meetings, with: Are these objections because that word is on the page, or because it it being viewed as an instruction manual for getting your hands on meth?” a committee member said. It was a fair question, as the committee was on a particular page where one character tells the other that the drug “brings even good people to their knees,” with nothing suggestive. A committee member guessed that the on-their-knees imagery may have been misconstrued as sexual, though it obviously was not. (The challenged pages in many titles reflect the work of an automatic scan that picks out key words rather than deliberate, analytical, comprehensive reading skills.)

Then the committee leader cautioned: “I don’t think it’s our place to question the pages. It’s our place to evaluate. I don’t think it’s our place to look for motive or intention.” She then moved on to the next page–yet another page that left the committee members puzzled over what could be objectionable, as when it appeared that a page was flagged because of the word “transvestite.”

“Because the word transvestite is offensive?” one member asked.

It was the latest in a series of more than a dozen such committee reviews tackling 44 challenges to 22 titles filed by just three individuals in the county–Terri McDonald, Shannon Rambow, and Cheryl Lackey, members of the vigilante group known as “moms for liberty.”

This particular challenge was filed by McDonald, who challenged the book’s presence at FPC, Matanzas and Indian Trails Middle School, even though it is not on the shelves at the middle school, even though McDonald does not have children in school, and even though, as appears evident from all the challenges, McDonald has not necessarily read the book–and was not at Monday’s committee meeting. The trio’s challenges have all them been word for word, page for page cut and pasted from a national website that incites vigilantes to seek book bans by providing them with ready-made challenges, sparing them the need either to read the books or understand their purpose.

While the three challenger spend perhaps 20 minutes or half an hour cutting and pasting their challenges before turning them in to the school district, they have caused the district to stand up numerous school-based and district-based committees, to mobilize committee members, including numerous school faculty members, all of whom have devoted hundreds of hours, unpaid, to go through the deliberative process of reviewing each book and debating its merits in committee discussions like Monday’s. Despite that, some school board members who favor book bans have ridiculed the process as being one-sided. Committees have voted to retain most books, but by no means all.

On Monday, only one person attended the committee review at Matanzas High school, other than a reporter: Will Furry, one of two school board members elected with the support of the “moms for liberty” who, last month, voted to ban a book when, for the first time in the district’s history, a book challenge was appealed all the way to the school board. (The book survived a ban in a 3-2 vote.) He said he was there “just to observe.” He did not engage with the committee members before the meeting, left immediately after the committees voted, and kept walking away, not answering, when asked what he thought of the process.

The challenge to Crank was filed on allegations that it “contains explicit excerpts involving sexual intercourse and sexual battery involving minors and explicit excerpt [sic.] sensationalizing illegal drug use.”

Committee members disagreed. There are passages depicting sexual encounters, including a rape, but the members found them all figurative rather than explicit, with never an endorsement–either for the promiscuity or the drug use. “Not salacious. It’s aggravated assault,” one member said of the rape. “And it’s hard to read, but that’s the point. Does it glorify or give instruction on how to do this? This is explicitly a warning, a caution of what this type of culture can yield.”

“You are very uncomfortable, but not by the words,” another member said.

As to the depictions of drug use, which are central to the challenge, a committee member who teaches at Matanzas made this observation: “When I walk down that hallway over there,” he said, referring to one of the school’s five Programs of Study–its law and justice program– “we have a crime scene class. There are posters of drug use and effects on the wall created by students. LSD, crystal meth, marijuana. It’s being taught explicitly in a class.”

The implication was that while the material is taught explicitly in a class, it is bannable in the form of a book that a student may voluntarily choose to read–and choose to read a book that would in no way lends any appeal to the behavior described: “I really appreciated that none of it, even in the moment when she is so high, none of it is glorified,” a committee member said. “It is immediately always brought to how awful this is, like there’s not even a page rate that I would think any reasonable person would say, oh I would like to try this.”

Last month the American Library Association reported that book challenges doubled in 2022, with 2,571 titles targeted, with 58 percent of the titles sitting on school library shelves, overwhelmingly as self-selected books (that is, books students choose to borrow voluntarily on their own, as opposed to books assigned in class), and with the majority “written by or about members of the LGBTQIA+ community and people of color,” according to the ALA. In that sense, Crank is an exception. It has cracked the top-10 most-banned book list only once in the two decades since publication, in 2010.

Monday’s vote, while unanimous, left some committee members dispirited over the process, now that such votes may not amount to much: last month, despite two school based committees and a district committee all voting unanimously to keep The Nowhere Girls on the shelves, it took only the superintendent’s decision to override all two dozen votes and decree that the book would be banned anyway.

Lou says

Radical Right have to be voted out at next election before they turn our country into a Fascist State.