It’s difficult to judge which of the two stories told about Sisco Deen is the more Sisco of the two–the time when he was hauled off to jail for stealing candy or the time when he was thrown off a moving Jeep as he was trying to pee off its side.

Many other stories were told about Deen at the memorial, which drew 132 people from four generations and almost as many continents. Deen died on Aug. 31 of his last cancer. He was 83.

They’d converged on Cattleman’s Hall at the county fairgrounds Wednesday afternoon to celebrate the life of the man they called “Mr. Flagler County,” the “card catalogue of Flagler County,” the co-conspiracist (with Carl Laundrie) who saved Flagler County history, and the man who taught one of his old lifeguard buddies Butch how to date four girls in one night.

But those two stories stood out like Odyssean strays begging to be memorialized, as Ed Siarkowicz, the current president of the Flagler County Historical Society, did. “You spent hours listening to your dad’s stories and they’re fascinating,” he told some of Deen’s stepchildren who were present. “The favorite story I’ve ever heard him tell goes back to the days of his youth when him and his probably early teen friends had discovered a way into the potato packing plant that was in Bunnell. They found a window that was not locked. They snuck their way in, they scurried up the conveyor belt, wandered through the building and came across the guard’s office that was unoccupied, except for a dish of candy that was sitting on the desk. So they raided the candy dish, they put it all in their pockets, and then they left.”

They did it again the following week. The third week the dish was empty. The guard’s office was not. There was the guard, appearing behind them. The guard and the sheriff. “We were about ready to drop something in our drawers,” were Sisco’s words. They were put in a squad car and hauled off to the courthouse. “Went into the courtroom. And there sat Sisco’s uncle, the judge. And in the witness box were the parents of each of the kids. And he said, ‘we looked around and we realized we are done for.’ What ensued was a very long lecture about choices in life, and how if you’re going to be doing this to the potato packing plant, what are you going to do when you’re 20?”

The judge found them guilty (that was obviously when due process was only a suggestion in Flagler County), and the boys were put back in the squad car and sent to the jail by the water tower. “On the way,” Siarkowicz continued, “they must have preempted the inmates with getting them all riled up. Cisco said they probably gave them an extra extra piece of meat for dinner. But they antagonized them, they put them in the cell. They locked them up. And they looked at them and said, We’re going to leave you here to sit and think about the direction that you want your life to be.” Of course he chose wisely.

As he would tell the story, which he apparently did often, perhaps fostering its Homeric dimensions with each retelling, Sisco would make clear that it wasn’t just about stealing candy, them stealing candy. “It was the nature of the community back then that came together to make sure that those boys were going to straighten up,” Siarkowicz said.

At least long enough to get on that Jeep. That story was told by one of his childhood friends and fellow-lifeguards. The group was driving on the beach north from Ormond Beach. They couldn’t stop once they hit the coquina sands or they’d get stuck. But nature was calling on Sisco. The driver told him to stand up, hold on to a metal bar and “do your thing.” Sisco did. Then there was a thump. He’d fallen over the side. As Sisco explained it, “I had a hand on the [metal] bar, a hand on my–thing, and I guess I let loose of the wrong one.”

So it went, in an hour-long memorial fashioned on the Quaker model, where sermons and formal rituals have no place and anyone moved to say something may do so. Edging Sisco away from Southern Baptists and into Quakerism had been his wife Gloria’s doing.

Before his death Deen had asked that none other than Charles “Skeeter” Cowart be the one to read a prayer at the memorial. Cowart is the 40-year-old Flagler County native and Deen neighbor who some years ago had “a rough patch that I went through,” as he put it to the congregation (rough and quite public, usually brought on by drinking). It had taken a little more than candy-dish shock therapy, but Skeeter had straightened up, and Deen had played a characteristically non-judgmental role in that rehabilitation. “He would always encourage, he never was trying to tell me what to do,” Skeeter said. “He just always continued to say, you’ll figure it out soon enough and such. But I did eventually figure that out.”

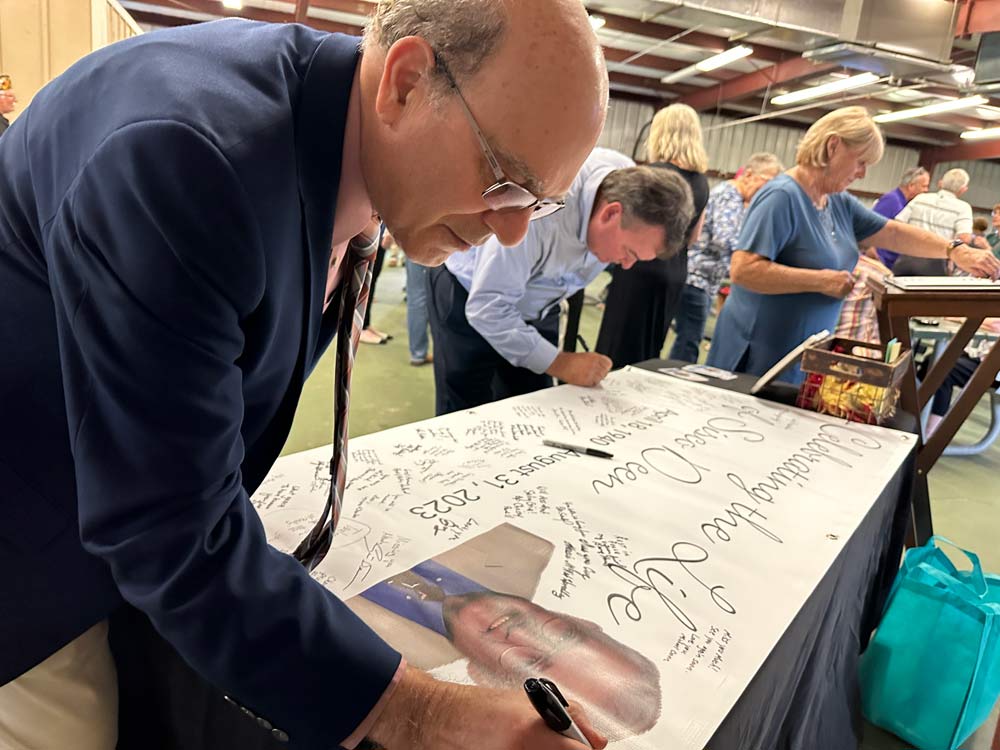

A long banner with Sisco’s portrait invited guests to fill it in with black-marker farewells, and they did: “Thank you for your service to country and the American Legion.” “You always were a ray of sunshine!” “Thanks for helping me know the history of Flagler County!” “What grace to have known you.” The hearts, the expressions of love, the diverse census of signatures bore testimony to Sisco’s “community of service,” as his son Devin put it, and the way he accepted people for who they were: not a as simple as it may seem today, not in last-century Bunnell, a time and place when some people were not allowed but to stay in their place, and others were invisible.

He found time for anyone mining the county’s history, no matter where he was, as when Kimble Medley, who was working on what turned into a major project and a book on the county’s suffragettes, heard back from him when he was on safari in Africa: she was looking for the name of the very first woman who registered to vote after the ratification of the 19th Amendment. It was Alice Scott Abbott, who may or may not have voted for George Hanns for County Commission.

Hanns, who served as commissioner for 24 years until 2016, was at the memorial, as was County Commissioner Andy Dance, both of whom had known Sisco well. Deen had teamed up with Laundrie to pull off the county’s centennial in 2017 in grand, historical style.

Deen’s legacy will endure in many ways–his archival treasures, which include the only deep pictorial history of the county, his documentation of Flagler County family histories and death records, and the planned re-naming–the County Commission willing–of the annex behind Holden House as the Sisco Deen Research Library. The county and cities will also be petitioned to name April 18, Sisco’s birthday (which he shares with Clarence Darrow, another stubborn man of justice), Sisco Deen Day in perpetuity.

“Sisco sister has said that whenever an older person passes away, it’s like a library of information burning to the ground,” Siarkowicz, the historical society president. “What kind of library have we lost with the passing of Sisco? It’s got to be on the level of the Library of Alexandria.”

![]()

Leave a Reply