The prosecution in the trial of Marcus Chamblin for the murder of Deon O’Neil Jenkins outside a Palm Coast Circle K in 2019 drew circles of circumstantial evidence around Chamblin, some of it damning, as the evidence portion of the case stumbled to an end on the fifth day of trial today.

But the defense was also effective at showing the state’s flawed star witness—Jerod Humphrey, a drug dealer sprung out of jail in Virginia to testify here–to have lied often. Humphrey’s behavior on the witness on the stand was a nightmare for the prosecution, and a gift to the defense: Humphrey couldn’t have shown more contempt for the proceedings if he’d tried. He was caught in a series of contradictions, or what the defense will contrive as lies.

p

Paradoxically, there was nothing ungenuine about Humphrey’s two hours and 10 minutes on the stand, longest of any witness all week: this was just not his stage, he didn’t want roped into this drama, and he made that clear below a tower of dreads the jury saw more often than his face as he more often looked down than anywhere else. He spoke as if he was utterly, desperately bored, and somehow made it riveting.

The defense’s strategy relies on pixelating the picture the prosecution is drawing with a lot of noise in order to show by inference, with far less circumstantial evidence than the state has marshaled, that Humphrey is the killer, not Chamblin. The state has to prove its case. The defense only has to raise reasonable doubt. The noise doesn’t have to be true. It only has to be theoretically plausible. It’s not a terribly high bar, especially with a jury of 12, any one of whom can prevent a guilty verdict. Such a verdict must be unanimous.

Nevertheless the prosecution is hoping that the jury can discern noise from evidence in a case rich in both.

The jury went home for the weekend, to return Monday for closing arguments and deliberations. Lawyers don’t like that kind of split. It gives the jury too much time to forget, to fuzz up what its members have heard and cook up its own theories, to sneak a few looks at media coverage of the case or overhear a spouse or a friend talk about it.

The lawyers had no choice. It’s one of the more technically complex cases in recent memory–Flagler County Sheriff Rick Staly once called the 15-month investigation the single-most extensive murder investigation in the agency’s history. The witness list exceeded 140 at one point, and while the state called only a quarter of them, it was still unusual for a criminal case in Flagler.

There was never an explicit admission, never an explicitly identifiable image placing Chamblin at the scene as there was of Derrius Bauer, his co-defendant, who goes on trial in September. Bauer is seen about 20 minutes before the shooting as he stood outside the Circle K at Palm Coast Parkway and Belle Terre Parkway, before driving off. Prosecutors established through cell data that he was in feverish contact with Chamblin who was on foot nearby for that stretch. There was never any contact with Humphrey.

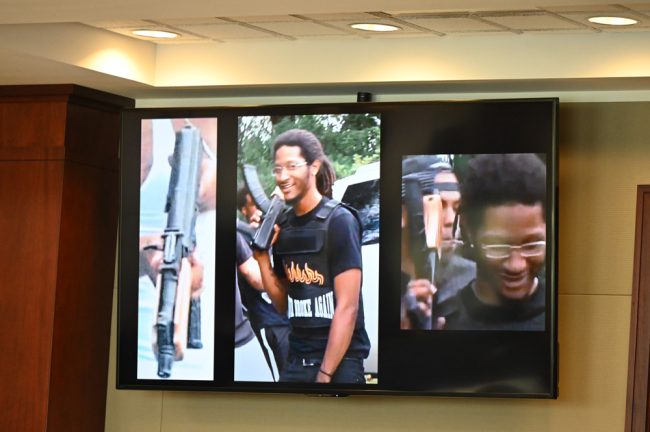

The state had to prove that Chamblin was the shooter based on a lot of that cell phone location data, on plenty of surveillance video showing the intentionally hooded shooter before, during and after the shooting, written lyrics, social media postings, and witness interviews. There was no lack of any of that evidence. Some of it will stand out for the jury beyond the mass of more technical evidence it heard, especially in the last two days. The evidence placed the AK-47-style Draco gun in Chamblin’s tattooed hand. It connected him by unfailing DNA to the kind of hoody and pants the shooter is seen wearing in surveillance video–the hoody and pants found bundled in Bauer’s car, which Chamblin had ridden. It connected him to a rap video showing him with the gun, to Instagram postings showing him with the gun, to Facebook messages very vaguely talking about his animus toward Jenkins, the victim.

So the circles closed around Chamblin methodically, concentrically, leaving little room for the defense to breathe life into its claim that Humphrey killed O’Neil over a drug debt.

“Nah, and I definitely don’t know who that is,” Humphrey said on the stand today.

The prosecution never established a believable motive for Chamblin to kill Jenkins, other than that Chamblin was “pissed.” But Terence Lenamon, the laconic defense attorney, never established that Humphrey had ever known Jenkins, either, or to have dealt him drugs, let alone kill him, especially when the killing took place around the time when Humphrey had come into a life-insurance payout, after his father’s death, of over $40,000.

The night of the killing, he’d rented two rooms for himself and a girlfriend, and for Chamblin and Bauer, at the Red Roof Inn not far from the Circle K. He and his girlfriend “fornicated” that night, he said, and when he wasn;t fornicating, and she was sleeping, he was getting his hair done by another woman in the room Chamblin and Bauer were using. That’s where, he testified, he saw the two men leave after Chamblin, after speaking with his brother, got angry about something jenkins had done. Chamblin left with the gun.

The prosecution did establish that there’d been not a single contact between Jenkins and Humphrey, based on an entire download of Jenkins’s phone, though Jenkis was a compulsive texter.

For his testimony today, Humphrey was brought in from a Virginia jail where he’s serving time for failure to pay child support. He did not want to be here. He made that clear. He was surly, as if shaken out of a stupor, or as if he’d been heavily medicated. He spoke almost inaudibly, intentionally. He never looked at the jury, barely looked at Assistant State Attorney Jason Lewis as Lewis questioned him with remarkable patience–he was a state’s witness, after all.

But if he was making every effort to be contemptuous of the proceeding and off-putting to his questioners, if not disrespectful to the jury, he came across as uninterested in the whole deal–including not hint that he was interested in dissembling. He just didn;lt want to be bothered, and lying would have seemed to take to much effort. He acknowledged that some of his statements today were different than what he’d said in deposition, but he neither challenged Lenamon about it nor seemed bothered, other than to occasionally suggest that what his written statements said may not have been what he meant. His impenetrable demeanor certainly lent credence to that possibility: he was very good at being misunderstood today.

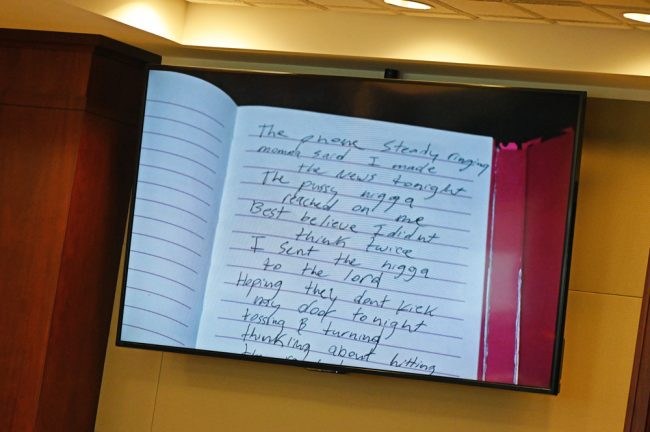

The prosecution is hoping two pieces of evidence may have disproportionate force with the jury. One is a set of lyrics written in Chamblin’s hand and reflecting a mixture of brutality and pathos that the prosecution says amounts to a confession: “The phone steady ringing mom said I made the news tonight / The pussy nigga reached on me / Best believe I didn’t think twice / I sent the nigga to the lord / hoping they don’t kick my door tonight / tossing & turning thinking about hitting the road tonight.”

In fact, he did: he, Bauer and Humphrey drove back to Virginia, where they were from, less than a day after the shooting, after returning to Palatka, where they’d been staying. Those lyrics, to the prosecution, are a confession: here’s Chamblin–whose handwriting was authenticated, whose fingerprints were all over those pages in an oddly feminine, pink notebook–describing a killing within days of the murder.

The second piece of evidence that weighs heavily in the prosecution’s favor is a clip showing Chamblin’s gait–a very particular gait that Flagler County Sheriff’s Detective Augustin Rodriguez described to the jury as it flashed on screen: “Left foot up, right foot out, left foot up, right foot out.” Augustin also described the footprints of the shooter walking with wet socks on concrete, then showed the video he surreptitiously shot of Chamblin walking from one interview room to another, a video Rodriguez intentionally shot to compare to the gait on surveillance video. It was a match. In this case, it is almost as strong a match as fingerprints.

Earlier Lenamon confronted Rodriguez, who’d interviewed perhaps 100 witnesses, with the question he’d wanted to ask all along: “Isn’t it true you had the habit of sharing a lot of information with people whom you were interviewing about your theory about this investigation?” Rodriguez acknowledged that he’d shared some of that information with Humphrey.

Behind Lenamon’s question is his theory that Rodriguez gave Humphrey enough information for Humphrey to extricate himself out of the responsibility. But if Lenamon hoped to elicit that sort of corroboration from Humphrey, even in the form of noise, he didn’t seem to have made it stick. There was a so-what element to some of the evidence he showed up, as, for instance, the Social Security card and bank statements Humphrey had left in Bauer’s car after the car was searched in Clay County. No one had denied that Humphrey had hung out with Bauer and Chamblin at length.

And Lewis had beat Lenamon to the punch when it was Lewis, not Lenamon, who revealed that Humphrey had been paid $2,000 to speak with the investigator. All that added was more evidence not so much about the killing of Deon Jenkins but about circumstances as sordid the night of the murder as those that shadowed the investigation as it unfolded over three states and 15 months.

![]()

Joe D says

What a CIRCUS….and a LIFE permanently snuffed out…seemingly without a second thought or CARE….how SAD!