The most self-conscious of America’s great writers, Philip Roth for years has been categorizing his novels for us as if to suggest there’s never really been just one Roth. It’s part of the character he’s been creating about himself since Portony’s Complaint half a century ago: Don’t define me, don’t fence me in, don’t call me Jewish just because I’m Jewish, don’t even call me black if I’m born black and want to pass myself off as white (the subplot of The Human Stain). For that matter, don’t call me Roth, or limit me to a single Roth. He can’t even control his own Roths: in Operation Shylock, another Philip Roth impersonates him in Israel and invents a whole ideology of reverse-Zionism, urging Jews to return to their countries of origin. It’s never clear which Roth is which, just as it’s never been clear or how much of the books are Roth and how much are invention: true fiction makes the distinction irrelevant.

So there are the Zuckerman Books, with Nathan Zuckerman as an alter-ego who evolved from the unbearable self-absorption of Zuckerman Unbound and The Anatomy Lesson to the nearly epic power of American Pastoral and The Human Stain (Roth killed an Alzheimer’s-stalked Zuckerman in 2007 with Exit Ghost). There are the Kepesh Books, starring the academic David Kepesh, whose most famous incarnation was as a 155-pound breast in Roth’s hilarious reworking of Kafka’s “Metamorphosis” (“They tell me I am now an organism with the general shape of a football, or a dirigible.”) Roth killed Kepesh in The Dying Animal 10 years ago. There are the “Other Books,” among them some of Roth’s best: Goodbye Columbus (his first), Portnoy’s Complaint (one of the late 1960s most sought-after masturbation manuals) and Shabbath’s Theater, the geezer’s guide to Portnoy. There are even the “Roth Novels,” the last of which—The Plot Against America, imagining a Nazi-sympathizing America in World War II—read like an unhappy pun on Bush’s America.

In his hypochondriac 70s, Philip Roth isn’t writing big novels anymore. He’s writing novella-length elegies under the latest of his categories: “Nemeses: Short Novels.” Four of them, each exploring one or two of those limitations in us that can define a life, rarely for the better. It’s Roth officiating at the human condition’s memorial service. Everyman, Indignation and The Humbling are told by protagonists at or beyond the grave, doing what we all do at the end of rougher days, but for a lifetime’s worth: retracing steps, circling vulture-like over the woulds and shoulds of failed marriages, regrets, botched expectations—“the vitriolic despondency of one once assertively in the middle of everything who was now in the middle of nothing.” Roth does a lot of character-assassination in these books, too, as if to cheat “the menace of oblivion” out of its last pleasure.

Nemesis is the latest and last of the four, just published. It can be read as a smaller-scaled re-writing of Camus’ Plague (and nothing to do with “Star Trek Nemesis,” the tenth movie in that cluttered franchise), but not for long: the book’s larger sweep on the effects of false fears and hysteria, of mob anxieties that make it “possible to grow suspicious of almost anything,” gives way in the second half to the narrower conceits of the plague’s effects on a single character, whose depth and appeal are not as compelling as Roth tries to make them. Zuckerman is not dead after all.

It’s the summer of 1944 in Newark, N.J. A polio epidemic is besieging the city. Bucky Cantor is 23. His bad eyes have kept him out of the war, to his great disappointment. He’s otherwise strong, virile and moral, the son of a mother who died in childbirth and a crooked father. He’s been raised by his grandparents and still lives with them. Mr. Cantor is a phys ed teacher and a playground director who wants to teach kids to excel in sports and sportsmanship and studies: “He wanted to teach them what his grandfather had taught him: toughness and determination, to be physically brave and physically fit and never to allow themselves to be pushed around or, just because they knew how to use their brains, to be defamed as Jewish weaklings and sissies.”

He leads by example. When a bunch of Italian bullies try to intimidate the playground’s children (“we’re spreadin’ polio,” one of the thoughs says), Cantor stands them down. But when some of the children who come to his playground begin to get sick and die from polio, parents blame him. “This was his first direct confrontation with vile accusation and intemperate hatred, and it had unstrung him far more than dealing with the ten menacing Italians at the playground.” More children die. He visualizes them in their pine boxes: one day they’re with him, vital as ever, the next they’re in iron lungs, then dead. Roth’s background canvass of Newark’s Weequahic Section, where he grew up—from the sociology of the city’s prejudices to “the citywide stink of Seacaucus”—recalls the more nostalgic pages of The Plot Against America or Patrimony, the memoir of his father’s last days. In Nemesisi nostalgia sets up to Bucky Cantor’s unhappy story, the end point of his glory days.

That summer of 1944 he was in love with Marcia Steinberg. She’d left the city for a camp in the Pocono Mountains with her two sisters. He’d proposed. She’d pleaded with him to join her. He’d refused: “it would be hard to shun the responsibilities of his job any more execrably than by decamping to join her in the Pocono Mountains.” Even as the epidemic worsened, Marcia’s father, who plays the role of a sage in Roth’s small universe, tells Bucky why quarantines and lockdowns are wrong, why he should keep at his job: “The alternative isn’t to lock them up in their houses and fill them with dread. I’m against the frightening of Jewish kids. I’m against the frightening of Jews, period. That was Europe, that’s why Jews fled. This is America. The less fear the better. Fear unmans us. Fear degrades us. Fostering less fear—that’s your job and mine.”

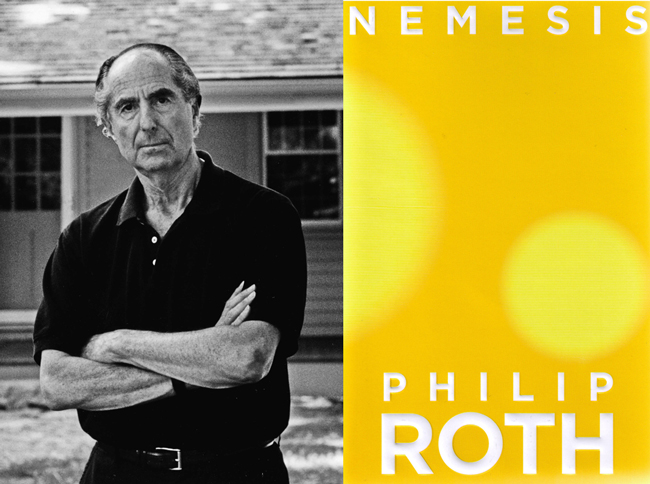

Nemesis, by Philip Roth

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

280 pp., $26

He doesn’t listen. In Newark, there’s polio. In the Poconos, there’s sex. He decamps. Of course, the terrible happens. “It was six untroubled days later—the best days at the camp so far, lavish July light thickly spread everywhere, six masterpiece mountain midsummer days, one replicating the other—that someone stumbled jerkily, as if his ankles were in chains, to the Comanche cabin’s bathroom at three a.m.” Polio respects no borders. Nor does fear.

But just as disease tends to make the diseased focus obsessively on themselves at the expense of their surroundings, Roth’s novel from that point on devolves into an obsessive meditation by Bucky Cantor about Bucky Cantor—his decision to leave Newark, the consequences of his choice, his decision to compound one decamping with another. It is a tale of degradation framed in Cantor’s Job-like rebellion against God—He who “sticks His shiv” in people’s backs—a rebellion that surprisingly, in Roth’s hands, produces some of the flimsier pages of the book: this is Bucky reflecting on his own fate, not that of, say, 6 million Jews who perished in the Holocaust while he was gallivanting around Newark and the Poconos.

The dissonance is jarring, however noble its motives. Roth is aware of the weakness of his character, or rather of his weakened character. It’s left up to the Zuckerman-like narrator to set things straight a little, putting a little muscle back where Bucky Cantor has given up: “His conception of God was of an omnipotent being who was a union not of three persons in one God-head, as in Christianity, but of two—a sick fuck and an evil genius. To my atheistic mind, proposing such a God was certainly no more ridiculous than giving credence to the deities sustaining billions of others; as for Bucky’s rebellion against Him, it struck me as absurd simply because there was no need for it. […] That it is a proliferating virus will not satisfy him. Instead he looks desperately for a deeper cause, this martyr, this maniac of the why, and finds the why either in God or in himself or, mystically, mysteriously, in their dreadful joining together as the sole destroyer. I have to say that however much I might sympathize with the amassing of woes that had blighted his life, this is nothing more than stupid hubris, not the hubris of will or desire but the hubris of fantastical, childish religious interpretation.” (One of the advantages of Roth’s compulsive self-consciousness is his ability to cheat not only “the menace of oblivion” out of its last pleasure, but the menace of book critics out of theirs.)

They Came Like Swallows, William Maxwell’s 1937 novel (reissued two years ago by the Library of America), is also about a plague effects—the flu epidemic of 1918—and it also focuses on one character, the eldest son of a mother felled by the disease (and less so on the husband and the youngest boy). The overwhelming emotion of the story is not defeat or resentment but sadness at the helplessness of the living in the face of the implacability of death, as when the husband sees his wife’s corpse in her coffin: “He had not known that anything could be so white as they were—and so intensely quiet now with the life, with the identifying soul, gone out of them.” Maxwell, writing when he was 26 years old, was able to convey what Roth, at 77, was not: There is more to death and disease than the dying or the diseased.

Nemesis has more ambition than emotion, more polemic than truth: it sparkles in its many parts but just doesn’t seem to add up. That doesn’t make it a bad book. There are no such things with Roth, uneven though his novels have been (what prolific novelist isn’t uneven?). It just makes it a relatively unsatisfying one in light of Roth’s works, even when his four “Nemesis” books are read as a whole. The scope of each novel’s protagonist, as each novel progresses, narrows and dies without something more transcending taking place. Maybe that’s Roth’s intention in these four novels. There’s no maybe about life’s trajectory: it’s a narrowing toward death, usually an increasingly dismal narrowing—“the slow disgracing of the mind,” as Lawrence Durrell put it—with no way out. In that sense, Roth’s books are as much elegy as honest preparation. There’s no faulting him for not deluding us.

Leave a Reply