As any great achiever will tell you, school has very little to do with anyone’s education. Books do. The books that become indispensable, unfailing companions at any age well past the confines of school walls, books that turn a flashlight scurry under the covers into a child’s nightly ecstasies, library stacks that give college students more narcotic relief from toxic classroom texts than any drug, enormous book collections that, thanks to the conjuring of Kindle, give readers of any age an immediate escape from life’s daily desperations anywhere, at any time, at the swipe of a finger. A thousand years ago Pope Sylvester II was considered a magician simply because he read books.

A few hours ago and on this, coincidentally the 562nd anniversary to the day that the very first printed book rolled off Johannes Gutenberg’s press (it was a Bible), every child and most adults at Belle Terre Elementary School became magicians as classrooms buzzed with the spoken voices of the First Annual African-American Read-In. Community members and leaders from all over converged on all elementary grades, including a sheriff and an undersheriff, two school board members, a mayor, an NAACP president, almost two dozen first-responders and cops, other professionals, retired teachers, unretired sportsmen—they each took up a classroom from pre-K to sixth grade, book in hand, and for about half an hour, commanded the class with their reading.

There was for the second graders the unforgettable “Tar Beach” by the great artist and fierce activist Faith Ringgold, where Cassie Louise Lightfoot imagines herself soaring over Harlem and the rest of Depression-era New York City in a quilt of symbols and hints of the injustices below and possibilities ahead. There was for fourth graders the book NFL stars Tiki and Ronde Barber co-wrote, “Teammates,” a story of grit and self-confidence. There was “When I am Old with You” by Angela Johnson, a story of love between the generations (and a winner of the Coretta Scott King Award, among others). And there was for fifth graders Andrea Davis Pinkney’s “Duke Ellington,” about the great jazzman who had the good sense to turn down a scholarship and drop out of school to become that “brilliant assembler of other people’s music” (in David Schiff’s words) and one of the great notes in American music.

By the time Allen Harrell was done reading the book to his class of fifth graders, he had them actually dancing in the aisles to the sounds of Ellington’s “Take the A Train” playing from a laptop. “You’re getting in the groove with that,” he told them. “Go ahead, stand up, dance.” They did. “In order to get in the groove, you have to be able to hear the music,” he said as they got more excited than he’d expected.

“That was a great class,” Harrell said afterward. He’s a mentor for students at Belle Terre who retired from teaching American history at Indian Trails Middle School in 2014. He’d also majored in music in college, so the Ellington book was an ideal fit. :”We talked about Duke Ellington and his music, we talked about the difference between the classical music and the jazz, the different core structure in jazz versus classical, and we talked about the old language, the getting into the groove, the swing, and cats, and the terms they used in Duke Ellington’s time.”

None of this had even been thought about as February and Black History Month began.

(© FlaglerLive)

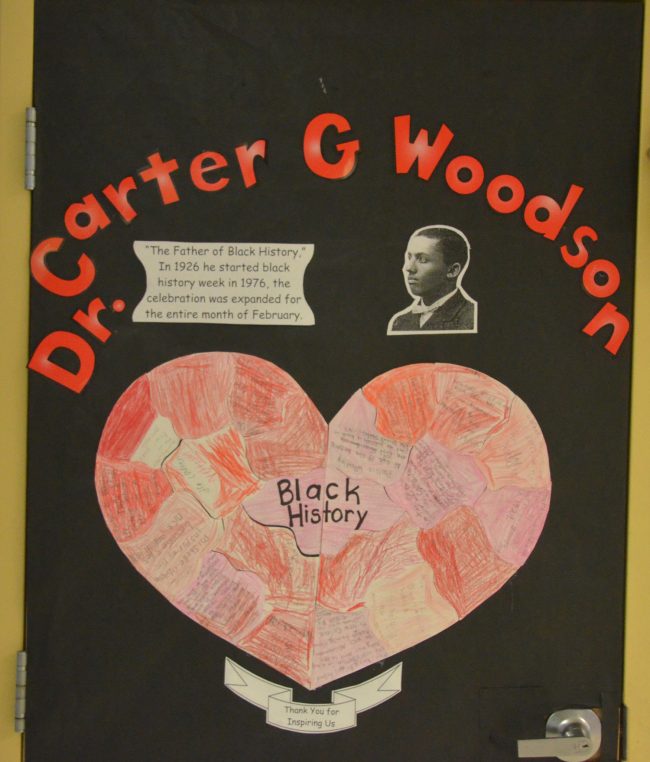

“This program came about, about two weeks ago,” Terence Culver, the principal at Belle Terre, told the gathering crowd of some 60 readers (“an incredible turnout across the district,” in School Board member Janet McDonald’s words) before they fanned out to their classrooms this morning. “I was thinking I had to do something. I’ve been here as an African-American principal for five years, and we have not done anything to celebrate Black History Month. Shame on me.” Thankfully for Culver’s five years of mis-education, the closest Carter G. Woodson was to the room was in a collage on a classroom door several buildings down, so he was relatively safe from further chastisement other than his own, and that didn’t last: by morning’s end he had atoned. He seemed so thrilled with the outcome that he was lunging photobomb-style in the middle of a photo-op gathering all the responders and top local politicians who’d turned out to read.

He had good reason: he’d managed to pull off a challenging event on very short notice, thanks in large part to his the team of teachers and employees he pooled–Sue Guarino, Latoya Lockhart, Priscilla Campbell, Vosie Miller and Jennifer Harris—and the sixth graders who ushered everyone in and out of their reading zones, among them compulsive reader Zander Zaidel, who happens to be into an unassigned book on Greek mythology these days. “It’s about all the gods and stuff,” he said.

The wonder of the morning becomes more evident the more one could grasp, from dropping in on as many classrooms as possible, the breadth and variety of readers and the sort of interactions they had with their listeners, no matter their age (readers or listeners.)

Linda Sharp-Matthews, president of the Flagler County NAACP, remembers taking part in the very first African-American Read-in, in 1990 in New York City, when she was teaching in the Bronx. She doesn’t remember the book she read then, but was grateful to have “Tar Beach” in her hand as she headed to her classroom to read it now. “It’s been such a long time since I’ve seen this book, I was shocked to see it, but I’m glad it’s here,” Sharp-Matthews said. The event, she said, “reinforces the need for our children to be exposed to literature and different authors, people they might not normally have been exposed to. And it reinforces reading. It supplements whatever you’re taught at school. You go home and you read something else. And see, that’s how I learned. Everything that I know, I didn’t get from school. I got from reading, reading books that had nothing to do with my homework assignments, reading about black history because my parents brought books home to supplement what I learned in school, which wasn’t a whole lot, so I knew what my history was.”

That, really, is why Woodson created what is today known as Black History Month—because American schools in his day had an amnesiac spot for black history, what he would describe as “the customary combat the Negroes have with Lily-white corruptionists.” But this was after all an elementary school, so even Woodson’s message was gently muted. It might have been more interesting had the 60 readers been invited to bring their own books to read, but also more unpredictable. Maybe next year: Culver intends to make this an annual event.

“It’s a way to reach out, it’s very good for the kids to hear and learn a bit about black history and a bit about the people in their communities,” said Anthony Cullings, who was reading in a second-grade classroom. Cullings, an information systems analyst, is president of the Bridge Building program, which develops basketball skills for students in all grades (and is hosting a Family Fun Day at Matanzas High School Saturday).

In Nancy McCoppin’s fifth grade classroom, here was Palm Coast Mayor Milissa Holland, the Duke Ellington done with, sitting through what turned into an excellent news conference at the hands of fifth graders. She had unwittingly triggered it by asking them what they wanted to see in their city, and out came the questions and comments—“more gyms and sports places,” “another library,” the inevitable question, even from children, about the city’s money-losing golf course (Holland made her usually valiant effort to defend the indefensible), and a student’s concern about what appeared to be a lot of car crashes. “One thing we really need to be working on,” the mayor said, “is telling our parents not to text and drive.” And on it went with talk of swales and ditches, debris removal and what makes a city livable. It wasn’t “Mood Indigo,” but it was vintage Holland.

A few doors down was Sheria Woods, a corrections deputy at the Flagler County jail, in uniform at the tail, end of a 16-hour shift, but still all smiles as she called on students with “yes, sir” and “yes, ma’am,” answering questions about what it took to become a deputy, whether children are jailed with adults, what it’s like to have to work the long hours. “Now that we’re short-staffed, that’s what most of our deputies do is work 16-plus hours,” she said, later specifying, when a student asked if deputies put in 24-hour shifts, that in fact the legal limit is 16 hours.

In a classroom of kindergarteners, anyone walking in and seeing the woman engaging the students, captivating them well enough that, unlike older students, they completely ignored the distraction of a reporter, would have thought her a seasoned teacher in her element, in her classroom. It was Colleen Conklin, the school board member. She’d once been a teacher, but that was many years ago, up near where Sharp-Matthews taught, but clearly, she had not lost her touch.

Nor had Davaughn Brown, though he’d never taught children, exactly: he’s a personal trainer and a mixed martial arts competitor, with the images of his most recent fight on his smartphone to prove it, to gaping students: they’d peppered him with questions about his sport after he’d dispensed with Ellington, and the questions kept coming as quickly as they had for the deputy, the mayor or, one assumes, the dozens of others who read to classes this morning.

Woodson, like Culver, would have certainly declared it a success, and would have appreciated the encouraging, nearly post-racial evolution of Black History Month as it was celebrated at Belle Terre Elementary. “What has the color to do with it?” Woodson had written in his seminal work. “Such a worker may be white, brown, yellow, or red, if he is heart and soul with the people whom he would serve.”

![]()

Jordyn says

The more community leaders interact with the children who live here, the more likely they will be to make decisions that benefit all of us. And the more children interact with community leaders, the more likely they will be to want to be productive members of the community themselves. This is a win-win, and exactly the type of community involvement in schools we should see more of! Hats off to Dr. Culver, BTES, and all of the participants. Please keep coming up with great ideas like this.

Anonymous says

when is white history month?

American History says

White history is 11 months out of the year.

Anonymous says

Black History is racism. If whites wanted a white history month they would be racist. Why can’t history just be plain ole history.

Anonymous says

Everyday when you get up and look in the mirror you are white. Therefore, you are ahead of the game. If you don’t take advantage of what’s available to you as a white person. Then it’s your fault. You can get a job, housing, better health care, education and all that life has to offer you. A person of color gets up has to remember she is black, a woman or a man, some or no education, before you leave.. These are 3 strikes against you. And the struggle to survive begins for rolling of the eyes when you walk down the street, negative remarks from people you don’t know, people stepping in front of you because they don’t want you behind them, and many more everyday experiences of more modern day racism. So why you ask “why isn’t their a WHITE HISTORY MONTH”? Could you handle what an African-American goes through daily? I don’t think so.

Carol Ogden says

As a kid who got her library card at age 3 and started a lifelong love affair with books and reading, I relished this story. You captured the eye-opening magic and inspiration of books on young minds. As always, well written and much enjoyed.