By Richard Gunderman

The book ignited a revolution, breaking free from conventional wisdom that said children required schedules, discipline and little affection. Instead, “The Common Sense Book of Baby and Childcare,” written by Dr. Benjamin Spock and published in 1946, encouraged parents to think for themselves and to trust their instincts.

Spock’s book was a huge best-seller, second in the U.S. only to the Bible. It sold more than 50 million copies and was translated into more than 40 languages. It helped to usher in a fundamental shift in how Americans approached parenting.

My wife and I are pediatric health professionals, but when our children were born, we rushed to buy Spock’s book. I have also researched Dr. Spock’s leadership in the field of pediatrics.

Before and after Spock

The timing of “Baby and Childcare” could hardly have been better. Two historical events had led Americans to put off childbearing: the Great Depression and World War II. With the war’s end in 1945, Americans began reproducing at an unprecedented rate – more than 76 million babies, the baby boom generation, were born from 1946 to 1964.

Child-rearing experts in the early 1900s promoted conformity and detachment in raising children. In 1928, John B. Watson, one of the founders of behaviorist psychology, argued that children should be treated as adults. Mothers should habituate their children to strict schedules, let them cry themselves to sleep and avoid too much love and attention. In his 1930 book, “Behaviorism,” he wrote:

“Never, never hug and kiss them, never let them sit in your lap. If you must, kiss them once on the forehead when they say goodnight. Shake hands with them in the morning.”

Spock advocated a radically different approach. He believed that children come into the world with distinct needs, interests and abilities, and that the core of good parenting is attending carefully to what each child requires at each stage of development.

www.shutterstock.com

Parents needed to trust themselves – or, as he wrote in the book’s first edition, “You know more than you think you do.” Human beings, after all, had been bearing and raising children long before John Watson, the invention of the printing press and the introduction of writing.

Spock emphasized parenting as a voyage of discovery. He treated mistakes as learning opportunities. True to his word, his own views evolved over time. In later editions of the book, he stopped treating parenting as “mothering,” introduced gender-neutral language for children and admitted that he had been wrong to warn against allowing babies to sleep on their backs.

A good start in life

Spock was born in 1903 in New Haven, Connecticut, where his father was a successful attorney. He attended elite institutions including Phillips Andover Academy and Yale University. While at Yale, the 6’4″ Spock rowed on the crew team, which represented the United States in the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris and won a gold medal.

He attended Yale School of Medicine before transferring to Columbia, where he graduated first in his class in 1929. While attending medical school, he married his first wife, Jane, who would later collaborate on his book. In addition to his pediatric training, Spock, who believed that the emotional aspects of child life were underemphasized, also trained in psychoanalysis.

During World War II, Spock joined the medical corps of the U.S. Navy Reserves and wrote “The Commonsense Book of Baby and Child Care.” He then took faculty positions at the University of Minnesota, the University of Pittsburgh and Case Western Reserve University, lecturing and appearing in popular media all over the world. In 1976, Spock married his second wife, Mary. In 1998, he died at the age of 94.

Anti-war activism and a legacy

During the 1960s, Spock became a political activist, opposing the Vietnam War and nuclear proliferation and supporting civil rights. In 1968, he was arrested for promoting nonviolent military draft resistance, although his conviction was overturned the following year.

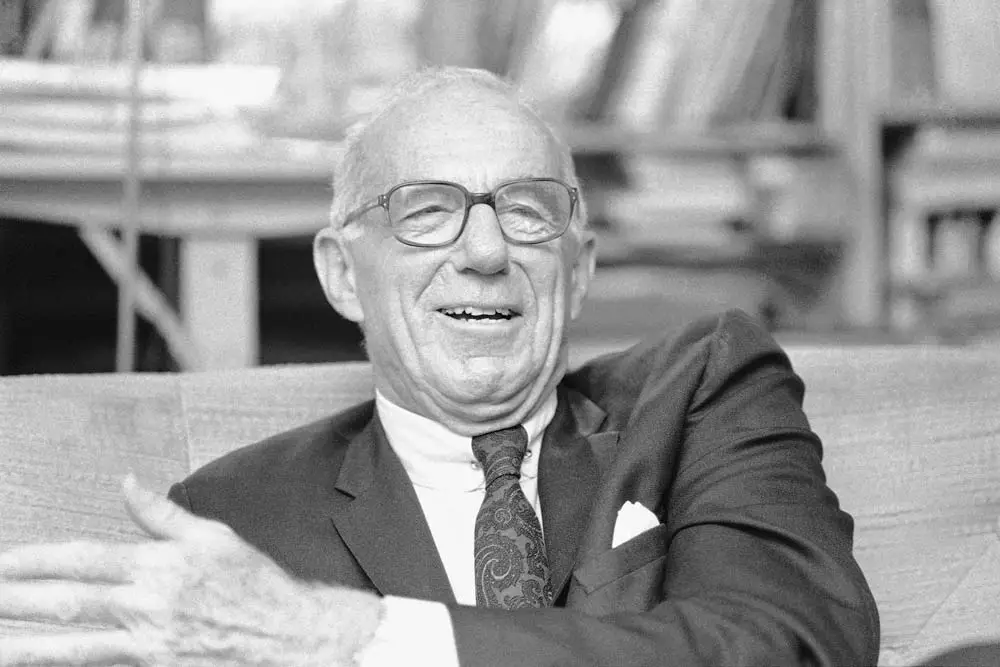

apimages.com

Despite Spock’s extraordinary popularity, he was not without detractors. Some attacked him for his political views, and others accused him of promoting excessive permissiveness. Others argued that he created unreasonable expectations for maternal dedication. Critics on both sides of the political spectrum complained that he had largely ignored fathers.

Spock’s most enduring legacy was his love of children. He said that if he had a fault as a pediatrician, it was his tendency to “whoop it up too much with children.” Above all, he dreamed of a world in which children would be “inspired by their opportunities for being helpful and loving.”

![]()

Richard Gunderman is Chancellor’s Professor of Medicine, Liberal Arts, and Philanthropy at Indiana University.

Leave a Reply