Click on the image for larger view. (© Pierre Tristam)

Flagler Reads Together, the annual celebration of books that falls in March, focuses this year on Ben Montgomery’s “Grandma Gatewood’s Walk,” the account of Emma Gatewood’s hike of the entire Appalachian Trail in 1955, when she was 67. She was the first woman to complete the trail alone. She would do so two more times. In 1999, FlaglerLive Editor Pierre Tristam was on assignment across the country, reporting and writing essays on each of the 50 states. He devoted his Virginia installment to the Appalachian Trail. A version of the essay, revised especially to reflect more current facts about the trail, appears below as part of Flagler Reads Together.

![]()

Whenever they drop off the Appalachian Trail for a swig of civilization, “thru-hikers,” as those who take on the trail’s 2,160 miles call themselves, are always grimy, blistered, and usually dazed by the shock of conveniences around them. Little things like a cold can of Coke or the flush of a toilet bowl, not to mention the thronelike elevation of its porcelain, make them giddy. Detached from their 40-pound backpacks they walk around with a phantom stoop and a gait that must confuse gravity. As worn as they are, they can’t beat the urge to keep moving. They walk to the nearest post office for a general delivery check, to the cheapest motel for a shower, to the most filling restaurant for a hot meal, preferably steak. They look and smell beastly, but you want to admire their ability to sweat wilderness when for the rest of us the Discovery Channel or clipping grass is the closest we get to nature anymore.

Looking closer, something is amiss. Their backpack is a $2,000 trove of equipment elite soldiers in most armies would kill for. It’s not that collapsible utensils and water purifiers and waterproof matches and stoves and gas bottles and flashlights that double up as compass or key ring or tweezers, plus $250 worth of guides, aren’t necessary for a thru-hike. Whole books are written about what to pack for the thing. But thru-hikers are no Daniel Boones. They’re not going on the trail to wrestle with bears and test their survival skills but to walk one of the prettiest and most predictable routes on the continent for five or six months. They needn’t carry weapons. They wouldn’t be allowed to use them, legally, and it is safer, for hikers and animals, to walk any part of the trail than to walk the average downtown street. Hikers’ only challenge, which is grueling enough, is to keep walking.

But the challenge is also a luxury, voluntary and pampered by the trappings of what goes for roughing it these days. Besides the $2,000 thru-hikers spend on their equipment, they must bank on at least another $2,000 to keep fed and marginally groomed for the 5 million steps required to make it between Springer Mountain, Ga., and Mount Katahdin, Me. That quickly rules out thru-hiking for the poor or for those who can’t afford to drop out of life’s bills and time-clocks for six months, which explains the high ratio of college students, early retirees and men (and much fewer women) transitioning from jobs or into widowhood or divorce. They like to take on a new identity by adopting trail names and lose themselves for a while, but within boundaries as clearly defining as the white blazes and rock cairns that mark the trail. With other hikers and towns always nearby, solitude is nonexistent, hunger is not an option, getting lost is impossible and bailing out, as four-fifths of the 20,000 thru-hikers who start every year do, is easy.

The beastliness crusting on thru-hikers when they abandon the trail drains off with the first shower, and with it the illusion that the Appalachian Trail is any kin of wilderness, by which I mean a swath of nature that is remote, virgin, free of human design and generally forbidding to human presence. The trail is a regulated, domesticated corridor of green that brushes against sprawl’s advance in some parts and coexists along highways in many others. It cuts through one of the richest natural habitats on the planet (the forest of the Eastern United States has reclaimed more land than at any point since before the American Revolution). But wilderness itself is extinct.

The beastliness crusting on thru-hikers when they abandon the trail drains off with the first shower, and with it the illusion that the Appalachian Trail is any kin of wilderness, by which I mean a swath of nature that is remote, virgin, free of human design and generally forbidding to human presence. The trail is a regulated, domesticated corridor of green that brushes against sprawl’s advance in some parts and coexists along highways in many others. It cuts through one of the richest natural habitats on the planet (the forest of the Eastern United States has reclaimed more land than at any point since before the American Revolution). But wilderness itself is extinct.

The trail doesn’t mourn the loss, although it doesn’t hide it. It rather effectively celebrates what remains by giving thru-hikers and their fantastic gear the outback illusion they crave, and by giving the 3 to 4 million other hikers who hitch a stretch of the trail for a weekend’s recreation a glimpse of what has been preserved, which is quite a lot. The trail, in sum, cross-cuts through America’s relationship with nature.

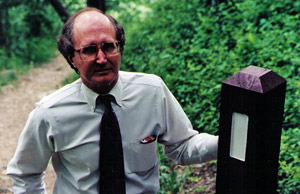

A thing so vast doesn’t exist by itself, although one of the wonders of the Appalachian Trail is the simplicity of its organization—the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, formerly known as the Appalachian Trail Conference, headquartered at Harpers Ferry. I missed the stone building the first two times I passed it. Like the trail itself, the Conservancy’s headquarters doesn’t blare its existence. Once inside I could have mistaken it for a minor visitor center, although that, too, is one of the illusions it creates: The ATC is a $3 million organization with a year-round staff of 30, not counting contractors and seasonal employees, or the volunteers whose 174,000 work-hours last year kept the trail as well defined as it is. Its 24,500 due-paying members are culled from a federation of 32 outdoors clubs along the trail.

The conservancy is ruled by a 15-member board, the ultimate authority on the trail’s real and quite imagined topography. It sets the trail’s official path (like the Mississippi, the AT’s course is always in flux). It weaves the 250 federal, state, county and municipal jurisdictions along the trail into its 5-million-step support group. And it hovers protectively over the trail’s myths. It’s a serious job. As with all inventions that become national folklore, the trail’s myths are more important than its reality. Myth-busters are as welcome as grizzlies.

One example. The most popular book to date on the Appalachian Trail is Bill Bryson’s “A Walk in the Woods,” published in 1998. By the following year it had sold 268,000 copies in hardback, making it bestseller caliber. It led to a surge of hikers on the trail, especially by thru-hikers. The surge hasn’t abated since (more than twice the number of thru-hikers complete the trail these days than in the 1980s), so much so that the Conservancy is considering a hiking limit. But the Conservancy’s publication committee debated hard over whether it should sell it “A Walk in the Woods.”

In particular Bryson makes fun of a Central Floridian called Mary Ellen, whom he and his trail companion meet by chance, as all trail encounters go, and who would not leave them alone, as some trail encounters go. Mary Ellen is described as having “an expanse of backside on which you could have projected motion pictures for, say, an army base.” Worse, Bryson writes, “She talked nonstop, except when she was clearing out her Eustachian tubes (which she did frequently) by pinching her nose and blowing out with a series of alarming snorts of a sort that would make a dog leave the sofa and get under a table in the next room.” Southern cab drivers also get it. So do Tennessee creationists.

Bryson also poked gentle fun at Emma Gatewood, the first woman to thru-hike the Appalachian Trail–in 1955, when she was 67–and who would go on to thru-hike it again and section-hike it once “despite being eccentric, poorly equipped, and a danger to herself (she was forever getting lost). He refers to her again toward the end of the book as someone who was “forever knocking on doors and asking where the heck she was.” Gatewood’s daughter Lucy didn’t appreciate the descriptions, writing Bryson that her mother was “eccentric, perhaps, but kindly, please. Lost, never, just misdirected.” Bryson, however, was quite correct: Gatewood’s sense of direction was strategically sound, but tactically wanting.

“A Walk in the Woods” is not just a riff of green humor or a hike-and-fawn book of what the writer Jose Knighton calls “eco-porn” but a serious work of reporting on the trail and much of the landscape it crosses. That’s why I suspect that the conservancy almost didn’t carry the book for a couple of other reasons that had nothing to do with Mary Ellen and her southern peers. The book reserves some blistering criticism for the National Park Service, which “has something of a tradition of making things extinct,” and the U.S. Forest Service, which, rather than managing the preservation of woodlands, is obsessed with building roads to make timber accessible to loggers. Hikers in the Maine woods can hear the chain saws. According to Bryson, the forest service’s 378,000 miles of roads in national forests “is eight times the total mileage of America’s interstate highway system,” and “the largest road system in the world in the control of a single body.” The conservancy maintains special relationships with both the National Park Service and the forest service, receiving $300,000 a year in federal funds to act as a sort of adjunct of the park system.

Neither service could have been happy with Bryson’s book, or its presence on shelves it subsidizes. Nor the trail conservancy. Bryson deflates the myth of the trail as equalizer, of the hiker as spiritual descendant of the noble savage. Hikers can be mere savages. Environmental policy can be ignoble. In the end, like the fractured vote on a Supreme Court decision, the ATC publications committee approved the book, 5-4.

In an amazing feat of continuity, the AT recognizes no obstacles. Rather than pretend that the more terrestrial world doesn’t exist, it puts the pastoral on hold while it crosses over bridges and under interstates or through the backyard of motels and service stations, as it does near Roanoke and many other towns. The trail is as much invention as concession, which is why it can reflect America just as it can escape it. In some ways, it escapes it too much.

The ATC’s Harpers Ferry headquarters is almost at the half-way point. Hikers invariably veer off the trail to check in, have their picture taken and posted in the annual record book and add their lines to the hikers’ register: “Having the time of my life.” “The metaphysical center of the trail: glad to be here.” “Hell yeah! Made it this far and it feels great . . . Don’t forget that Spam is good.”

The faces don’t change much. As I looked through two books of thru-hikers’ Polaroids laminated for posterity, the clearest picture that emerged was that of a community of hikers who were mostly men, mostly young, mostly bearded, and, tans aside, almost entirely white. Out of about 600 pictures, I noticed just one Asian. No blacks. No Hispanics. The Conservancy’s 15-member board is, not surprisingly, all white. Its 13-member “Advisory Circle” has one black member.

Myth-busting is unfortunately not the conservancy’s strong suit.

There comes a point where warts must be sidestepped and the trail picked up on its own terms.

At 4,010 feet, Stony Man Mountain is the second highest peak in Shenandoah National Park. It juts out of the forest canopy and hangs over the immense Shenandoah Valley’s sea of green so invitingly that, for a brief moment anyway, diving in feels like the thing to do. I was nearing the end of my pitiful nine-mile hike along the Appalachian Trail when the peak revealed itself, unannounced. I remembered my fear of heights and revised my view of the mountain into a classic overlook without the clang of car doors and the rush of gazers, although by then I already was exhausted with wonder. With gear consisting only of a camera and a set of guides, I’d spent the previous five hours doing what serious hikers can’t afford to do. I’d stopped at every odd-looking shrub or stately hemlock. I’d chased birds just to be able to identify them (I think I saw a yellow-rumped warbler, an indigo bunting and a red-headed woodpecker). I’d mourned for the murder-by-moths of mighty oaks, and found insect watching a waste of squints even if my Peterson field guide made centerfolds of beetles and flies.

But whatever the awesome view, the trail has its own momentum. It pulls you onward along the footpath as if you are invisibly attached to a train of marchers. Three thru-hikers passed at brief intervals as I sat on Stony Man Mountain. They stopped to chat, but they were hurrying to reach a restaurant before closing time, four hours south. Rush hour, even here.

![]()

Dave says

Why the thing about blacks, I guess you never heard of Robert Taylor the first Black man to hike the trail. And who cares about a mans backpack and gear, after all this is not he 1800’s. Boone never hiked the whole trail so why the mention. Again to your mention of blacks and Hispanics not on the trail, maybe they have other important things to do, did you ask any of them ?

I for one would be more worried about the encroachment of civilization on all things forest in the US and the cutting down of trees and destroying what will take an eternity to replace. And the placement of a large wind farm proposed just south of Pleasant Pond Mountain in Bingham Maine which can be viewed along the trail..

Daniel Booze says

Piece of cake…..I could walk it in my sleep !!!