On January 4, 2013, a single-engine plane carrying three people crashed into a house at 22 Utica Path in Palm Coast, killing the pilot Michael Anders, a 58-year-old school teacher, and his two passengers, Charisse Peoples, 42, and Duane L. Shaw, 59. Peoples had two sons, Anders two daughters.

On July 9, Anders’ daughters sued the federal government for wrongful death, accusing air traffic controllers of having misguided their father to Flagler County Airport instead of directing him to Ormond Beach Airport, which was nearer when the plane emergency began.

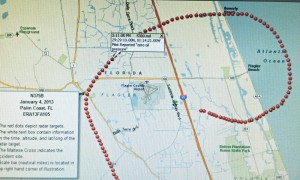

On Thursday, Peoples’s two sons, also through an estate administrator, filed a nearly identical lawsuit. Both lawsuits also claim air traffic controllers directed the plane to make its approach to Flagler County Airport through a wide-arc turn that took it over the ocean, delaying its landing, when it could have directed the plane to take a more direct approach.

The plane crashed three-quarters of a mile from the runway, 12 minutes after Anders had told controllers: “…we got a vibration in the prop, I need some help here.” It was at that point that a controller in Daytona Beach directed the plane to Flagler.

The two federal lawsuits were filed in Florida’s middle district in Orlando because the focus is mostly on the actions of air traffic controllers in Daytona Beach rather than in Flagler. The lawsuits are being handled by different law firms: Barry Newman of Jacksonville’s Spohrer and Dodd is representing Aubrey Anders, who filed the suit on behalf of herself and her sister. Timothy Loranger and other attorneys from Los Angeles’ Baum, Hedlund, Aristei and Goldman are representing Darrel Joseph, who filed the suit on behalf of Peoples’s two grown sons. (Agencies of the government may not be sued individually, but the lawsuits are clearly focused on the Federal Aviation Administration and its controllers’ actions.)

Other suits have resulted from the crash: Peoples’s sons in May 2014 sued the Anders estate and Sanders Flying Services, among others, also in a wrongful death claim that raises issues of negligence, blaming Anders and the company where the aircraft was serviced. The Anders sisters the same month filed a similar suit in federal court in Tennessee against Sanders Flying Services. Those suits are pending.

The lawsuits collectively, along with the National Transportation Safety Board’s detailed investigative report on the crash and other documents, open a broad window into the short, complicated and ultimately fatal history of the plane’s last flight, tracing its last minutes in detail down to the height of the tree branches the plane clipped as it crashed and the location of its various parts as the house on Utica Path burned.

Michael Anders and his friends had taken off at 1:11 p.m. from Saint Lucie County International Airport in his four-seater 1957 Beechcraft Bonanza. The trio was heading to Knoxville Downtown Island Airport. Peoples, who held a master’s degree in engineering, worked for United Technologies in Indianapolis. She and Shaw were returning from a vacation in the Bahamas.

Anders had owned the plane five years, but the NTSB investigators never found its maintenance records, concluding that they were destroyed in the crash. In a written statement to the NTSB, the workman who refueled the airplane at the St. Lucie airport reported that he noticed “visible oil leaks” on the plane’s nose gear strut. After he informed Anders of a fuel imbalance before refueling, Anders told him that the airplane’s right fuel pump was not working.

Traffic controllers did “briefly” consider Ormond airport, the NTSB investigation reveals, “however, because runway 8/26 was closed for construction and there had been a strong tailwind for runway 17, that airport was not an option.” So Anders was directed to Flagler.

“Our position was the tail-wind was not significant enough to prevent an attempted landing at Ormond,” Timothy Loranger, the lawyer representing the lawsuit filed on behalf of Peoples’s sons, said in an interview.

Anders was directed to make a landing so-called airport-surveillance approach at Flagler airport that was not “published”—in other words, that had not been made available to pilots in the official documentation that every airport provides. (An airport surveillance approach, the NTSB explains, “was a type of instrument approach wherein the air traffic controller issued instructions, for pilot compliance, based on an aircraft’s position in relation to the final approach course, and the distance from the end of the runway as displayed on the controller’s radar scope.”)

“Flagler County Airport did not have a published ASR approach,” the investigative report notes. “The controllers determined that to best handle the emergency it was necessary to offer the pilot an unpublished ASR approach to runway 29 at [Flagler] using area navigation (RNAV) approach minimums. This determination was based on the information obtained from the pilot, and the need for the pilot to conduct an instrument approach into the airport due to the [instrument flight rules] weather conditions.” The lawsuit notes that it was a controller’s decision, not the pilot’s, to make an “instrument approach” even as the controller was telling Anders to maintain altitude at 3,000 feet. The controller was doing so to keep the plane a safe distance from a tower near the airport.

“The controller should have understood that the loss of either a propeller, or engine, in a single-engine airplane constitutes a dire emergency and would limit an airplane’s ability to maintain altitude, much less climb,” the lawsuit states.

“The controller should have understood that the loss of either a propeller, or engine, in a single-engine airplane constitutes a dire emergency and would limit an airplane’s ability to maintain altitude, much less climb,” the lawsuit states.

At 2:09 p.m., Anders reported “zero oil pressure.” Five minutes later, a controller directed the plane to make a right turn. “This reflects that the controller, knowing the flight nay have a total power loss, recklessly vectored the flight over open water,” both lawsuits against the government state. At close to 2:16 p.m., the plane was four miles from Runway 29, but for the next two minutes repeated calls from controllers to the plane went unanswered. Finally at 2:18:27, the pilot radioed, “we need help, we’re coming in with smoke.”

Anders was told he was cleared to land.

Less than 30 seconds later, the Flagler tower informed the arrival controller that “the airplane did not make it to the airport,” the NTSB report states.

Anders, Peoples and Shaw had crashed on Utica Path after hitting a pine tree 60 feet above street level.

The Anders lawsuit against Sanders Flying Services states that before Michael Anders flew the plane to the Bahamas with his friends, Sanders replaced two engine cylinders that “were not new or appropriate parts for use on the aircraft.” The suit claims that one of the cylinders’ connecting rods broke, dislodged or loosened from the crankshaft journal, causing the vibration in the engine or the propeller. After breaking free, the rod pierced the crankcase just below the mounting flange, causing the loss in opil pressure and ultimately causing the plane to stall and crash.

The NTSB report found that “it could not be determined if this maintenance played a role in the accident.” The report concluded: ” The reason for the oil starvation could not be determined. Review of the air traffic control transcripts and interviews with the controllers revealed that they vectored the airplane such that it was unable to reach the airport. This was likely due to the weather conditions and the controllers’ incomplete understanding of the airplane’s mechanical condition (complete loss of power), which the pilot did not provide.”

Joseph Gambino, a 23-year veteran of the FAA, had been the coordinating controller in charge that day. He’d been working in Daytona Beach since 1996. He told investigators, according to the final report on the case, that “there was not anything he would have done differently during that time. He noted that that the controllers worked as a team and the [front line manager] did an outstanding job and trusted his controllers to do their jobs.”

“We filed a lawsuit because based on the facts we have, we feel strongly that the air traffic controllers were negligent in the way they performed their duties,” Loranger said. “We wouldn’t have filed a lawsuit unless we felt reasonably confident that our clients would be successful.” A news release issued by his firm notes that Baum Hedlund attorneys “have handled over 650 commercial and private aviation crash cases across the nation and abroad. The firm has recovered over $1.4 billion for clients in all of its areas of practice, including aviation accidents.”

![]()

Thank You says

Thanks to Michael and Lynn Seck a new home has been constructed on this site that brings beauty to this neighborhood.

Harrison H. McDonald says

I must say as a licensed pilot and registered mechanical engineer, based on the information in this article, flying a 67 year old single engine airplane over the Atlantic ocean with passengers soon after major engine repairs is incredibly irresponsible. This is made even more egregious that it was done in bad weather. The instruments needed for safe IFR flight are dependent on THE ENGINE RUNNING. Most engine failures occur soon after major engine repair. The engine probably should have been replaced instead of being “patched.” This would have been the pilot/owner;s decision.

YankeeExPat says

1957 Beechcraft Bonanza…….At what point does the metal structure of a plane reach its maximum life? I know that older planes can and are restored from the ground up, but are much more pedestrian planes such as these afforded the same scrutiny for possible failure?

Anonymous says

The V-Tail Bonanza has always been one of the most coveted private planes since it’s debut in the mid-50’s. It’s combination of speed, efficiency and beauty made it so. I myself remember sitting in Cecil Elementary School South of Pittsburgh in the early 60’s and every afternoon one would fly past the windows from Campbells Airport down the road. I swore then that one day I would learn to fly and get one for myself. And thirty years later, I did better. I got a Beechcraft Baron, a two engined stretched version of the Bonanza.

But the Bonanza did have it’s problems. It was a high-performance machine that demanded skills and attention to fly. So many newly prosperous businessmen bought them and did not get or keep their proficiency in them that the accident rate was higher than normal. So much that they coined the term “The Doctor in a Bonanza” syndrome to describe a person who could afford more airplane than he could handle and died as a result.

But the V tail model did eventually have issues with metal fatigue causing catastrophic failure of the tail section so bad the entire fleet was grounded until a modification package was developed in the 80’s. But all in all, it is a classic that is still admired by all pilots today and is still a viable personal transport 60 years after launch.

carol says

Not true Harrison,

That is why certified FBO exist. All engines can be repaired, all.

Anonymous says

From what I understand it was mostly if not all the pilots mistakes that lead to this. First NO service records found for the plane?? maybe just maybe it was not serviced properly. next the oil leak reported by the last person who saw the plane on the ground and the owner pilot paid no concern to it. To me most telling was that the pilot/owner did NOT call for an emergency he just said ~ The plane crashed three-quarters of a mile from the runway, 12 minutes after Anders had told controllers: “…we got a vibration in the prop, I need some help here.” It was at that point that a controller in Daytona Beach directed the plane to Flagler.~ I need some help. Ive been told had he specifically said emergency then the controllers would have taken different actions. The law suits are going after those who had the least understanding of exactly what was going on within the plane. Controllers only know as much of the situation as they are told.

Outsider says

Most accidents are the result of a chain of events and errors; this one, based upon the narrative is no different. The decision to put uncertified cylinders and other parts on the engine was the first link in the chain. The decision to fly the airplane with a fuel pump inoperative, while probably not a contributing factor is indicative of the pilot’s decision making processes. The decision to continue flying in spite of obvious amounts of oil leakage was another factor. Electing to fly a single engine aircraft in demanding weather situations over water with what may have been subpar maintenance on the engine is a major factor. Blaming the controllers, who acted professionally and made the correct decisions is ridiculous. They did the best they could in the situation they were forced into as a result of others’ questionable choices.

Gloria Lowery says

I am the Aunt of Charisse M. Peoples one of three people whom died when the plane crashed that she and her fiancée were traveling on from the Bahamas. Every day I think of my beautiful intelligent niece and I cry so often as I miss her presence in my life so much. My heart is still heavy with sadness from my baby being gone. I miss Charisse being with me on shopping trips and going to church service with me. God Bless you my angel until I see you in heaven. Love, Aunt Gloria