| Skip introduction and take me straight to today's installment. An introduction to American Impressions: I was the luckiest reporter on the planet. I’d proposed to my editors at the Lakeland Ledger to send me across the country and write an essay on each of the 50 states. They went for it, handing me two credit cards, a camera and the vehicle of my choice--a Chevy Venture I rigged up with a library and a bed.  I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I was not traveling to discover myself or get away from myself, I was not in search of America or of eternal truths. I’m not equipped for that sort of thing, being rather shallow, and I wasn’t going to pretend to understand a state or even a village from a passing week. Nor is this a travelog about food or fun places to visit or quirky people I met along the way. I was just a reporter, picking up stories here and there, choosing for each state one or two themes that struck me as telling about that part of the country, and hoping to build a mosaic of an America every inch a wonder and a puzzle of joys and sorrows to an immigrant hopelessly in love with his adopted country, despite and still. I hope you’ll enjoy the journey. --Pierre Tristam Previous installments:1. Introduction: The Day Before America | 2. Heartland | 3. The Road | 4. Alaska: The New Suburb | 5. Alaska Highway | 6. Montana: Backtracking Lewis and Clark | 7. Montana: Ghost of the Prairie | 8. North Dakota: A Life in Missiles | 9. South Dakota: Crazy |

An icy rain pelts the car sideways from a driving wind. We almost hydroplane on the rutted pavement then begin skidding from left to right after turning onto a narrower gravel road, the car a ping-pong ball between the ditches. Violent October rains are rare in northeast North Dakota, but Kate Stevenson is not driving me around in her muffler-challenged Mazda to show me the prettier side of her native state. She’s hunting for B-13, one of the 150 missile silos she grew up with, near her mother’s house.

Kate thinks and talks the way she drives, her mind able to juggle nuclear meditations with memories of childhood written on every section of prairie land around her hometown of Walhalla. We drive through Olga, or rather the Catholic church and the bar that now make up downtown Olga, once a thriving French settlement. “The church is very cute inside, very non-Vatican II, it’s still got the old statuettes,” Kate says, glancing at her missile map while surfing the muddy gravel. The map shows the location of every silo in the Grand Forks missile field, a peppering of round black dots more numerous than towns that stretches in an uneven band from the Canadian border down to I-94 near Fargo.

B-13 appears out of the gray, its cluster of light poles the sure give-away. Farmers don’t light up their fields. The military does.

Kate, an habitué of missile paraphernalia — she was writing a novel about life in the missile field — parks the car and invites me to have my first near-silo experience.

From one side the site looks nothing more than a patch of grass with a concrete slab in the middle and a chain-link fence topped with barbed wire. It could be mistaken for a neurotic septic tank. As we walk around the square, one of those sights symbolic of the nuclear age becomes more defined. The slab is a hexagonal lid several feet thick, engineered to slide or be blown open the moment its Minuteman missile has been targeted, ignited, and set loose to deliver a payload of destructive power measured in euphemisms, because it no longer fits the human imagination.

I stood outside the fence looking in, soaked and frozen. I thought of something Kate had said earlier: “The deep culture of this area is potlucks and hunting.” Not neighboring the seeds of thermonuclear war. How, then, had life been lived for so long in the company of weapons capable each to inflict and attract regional replicas of Armageddon? The question had attracted me to this corner of North Dakota, where Kate, 42 when we first met–we have stayed friends since–had grown up, and where her mother, Virginia Lillico, had lived for 82 years, predating the nuclear age, outliving the Cold War, and caring very little for either.

“I was too busy raising kids and taking dinner out,” Virginia said.

*

The Lillico house, sheltered from the bitter Dakota winds inside an arc of old oaks and cottonwoods on 60 acres of farmland, is as warm and inviting as the missile site was cold and forbidding. Instead of the “Use of deadly force authorized” sign found on active missile installations, the Lillico welcome mat announces that “One nice person and one old grouch live here.”

It was difficult to pick out the grouch. For most of the weekend I spent with the family, Conrad Lillico, who was 81, rested on the living room couch, his congestive heart acting up, and Virginia engaged Kate in duels of self-deprecation, a family sport like story-telling. Whenever Kate wasn’t taking me to the geographical subplots of her novel or correcting papers — she lives and teaches at Jamestown College (now the University of Jamestown), a three-hour drive due south — we talked around the kitchen table, interrupted only by Virginia’s cooking and card games.

Before the missiles, there was Florida, when Virginia’s family lived on the road to Auburndale in the 1920s.

“My dad bought a farm, sight unseen, 20 acres, seven acre orange grove,” Virginia recalled. “Father was a kind of a gambler, as my mother said. He’d rather play cards all night than do any work. So we packed up, mother dad and four girls. I was 9, the youngest was 2, and we took off for Florida, with no road maps.” They got their directions from filling station to filling station.

Savannah, she called “a mudhole. There were pigs in the streets.” The Florida farm wasn’t much better. “You’ve seen pictures of these houses in the backwoods, not painted, not nothing. It was three bedrooms, a kitchen and a living room. The seven acres of orange groves were at least 7 years old and had never been taken care of. They were tall. Dad had bought himself a headache. Then there was squatters in the house. It took us a week and a half to get them out. In the meantime we lived in a tent.”

The house was six miles out of Mascotte in lake County. People would stop and ask, “Is this the road to Auburndale? That was the town they wanted to go to, so we just told them — keep on going down the road. At that time the road was red clay.” She doesn’t remember going to Auburndale. “But I remember going to Lakeland because we visited friends there. It wasn’t a very big place at that time.” I was living in Lakeland at the time, so Virginia was throwing me a bone.

“Better than Savannah?” Kate asks.

“They didn’t have pigs in the streets.”

The family was in Florida five years, returning to Walhalla when Virginia’s grandfather died, leaving land to be tended. Married in 1935, mother to four kids, widowed in 1963, remarried, employed among other jobs as a postmistress and a checkout clerk, life for Virginia was a mix of ups and downs she recalls factually and jokingly, never sentimentally, as if to honor the pragmatism of her husband’s Icelandic ancestry. She had listened to H.G. Wells’ “War of the Worlds” when it came over the radio in 1935 but hadn’t for one second believed that Martians were invading earth.

“It didn’t make any sense that it happened overnight. Come on.”

“That probably is a precursor of mother’s opinion on the cold war,” Kate says.

And so the talk turns to missiles.

“I don’t know what year they started putting those silly things in the ground,” Virginia says. The sowing actually started in 1962. “Most people didn’t really give a hoot one way or the other. They thought they were being defended. I don’t think I really paid any attention. I was too busy raising a family to worry about it and I figured I was safe in North Dakota because we were in the middle of the country. I didn’t figure they’d go hunting for us.”

“I’ve always been conscious of it. It’s not something you don’t know about when you’re growing up as a kid,” Kate says. “There was that myth of North Dakota being the third nuclear power if we seceded. People get real proud about that sort of thing around here even though it wasn’t true. It’s even less true now. Then you read articles about people building bomb shelters. You worry about it.”

“I didn’t,” Virginia says “Your dad did. ‘They’re going to blow us up, they’re going to blow us up.’ What are you going to do about it?”

“It’s your philosophy, mom. I’m, much more neurotic than that,” Kate says, and turning to me: “Mom never wanted to prepare for nuclear war.” But who does? What does preparation entail? It’s not like preparing for Christmas, a burdensome enough chore roughly comparable to the Bataan death march. At least there’s an end point to the march for those who survive every December 25. You don’t want to survive a nuclear attack. Virginia’s neighborhood was lucky during the cold war. Soviet missiles had its name on them, probably more than a couple of warheads for each missile silo, so the chance of survival was blessedly nil even in makeshift shelters. Virginia knew better. She hadn’t waited for Carl Sagan to decide that nuclear winter was not her thing.

“We got some papers from the post office asking what we were going to do in case of an attack on the anti-ballistic missile site,” Virginia says. “I answered them kind of nasty like, I said we’re two miles from the site, why should I worry? We wouldn’t have time to hunt for anything. Why be prepared? What are you going to come out to? No, I’m not hunting for no shelter.”

*

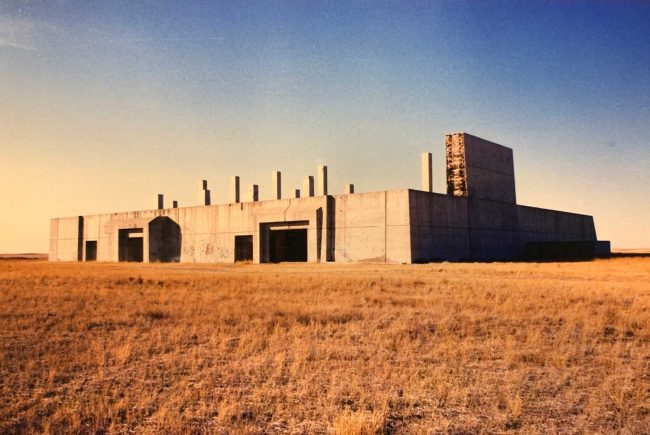

A week earlier in northeast Montana, near the town of Ledger, I had come across one of the Cold War’s unintentional ruins — an unfinished ABM site the military had stopped building in 1972 when the United States signed a treaty with the Soviet Union to limit ABM sites to one for each nation. (See: “Montana: Ghost of the Prairie.“)

The Ledger site, an acre-large mass of concrete once meant to resist nuclear attack, was turned over to graffiti and prairie swallows. The site that was finished sat two miles from Virginia’s house. She’d been unaware of my preamble in Ledger when she called her neighborhood Air Force Space Command’s 10th Space Warning Squadron and requested, successfully, that her daughter and I be let in for a visit, although the place is closed to the public except for an annual open house.

There it was, the finished version of what I’d seen in Montana, a windowless box of 58,000 square yards of concrete 120 feet high, 200 feet wide and 200 feet long at the base. And 8,000 tons of steel reinforcement. It’s actually a fancy radar, its slanted north face a collection of 6,800 pin-like antennas that supposedly can track a basketball 2,000 miles away. That’s what the techs inside the pyramid like to say, anyway, though there didn’t seem to be much point in tracking a basketball–or a warhead, for that matter, if all it was, was tracking. And that’s all it was. Yay!

It goes by the name of PAR, for “Perimeter Acquisition Radar,” kind of like calling Yankee Stadium a “Baseball Percussion Sector.” It was first designed to track incoming ICBMs and tell a sister-site in nearby Nekoma (pop. 50) where to aim its anti-ballistic missiles. That nearby site is an even bigger pyramid of concrete, dubbed by the locals “Nixon’s Pyramid.” They forgot the word scheme. (North Dakota Sen. Kent Conrad in a 2005 commemoration of Nekoma’s centennial, from the Senate floor, changed the name to the “Prairie Pyramid.”)

The complex went into operation on Oct. 1, 1975. It had cost $6 billion to get to that point ($33 billion in 2022 dollars). A month later, Congress decided no longer to fund it. “We have spent $5.7 billion preparing to defend ourselves against the intercontinental ballistic missile,” George Mahon, the Texas Democrat who chaired the House Appropriations Committee, had said. “If we had sone nothing, it would have been the same.”

The pyramid was mothballed, fulfilling what North Dakota Gov. William Guy had said several years earlier, that it would “be like other North Dakota facilities — obsolete before it can be built.” The PAR site became just an early-warning system, its radar keeping a look-out for submarine-launched missiles from Canada’s Hudson Bay. It also tracks satellite traffic. Tracking Mir, the decrepit Russian space station, seemed to be a favorite pastime for the two-men radar crews on duty when we visited.

Our guide was Lt. Andy Olsen, a 28-year-old missile crew commander who had just gotten off duty when he met us. The place was a quarter century out of date, with more clunky technology than half the brainpower of a Pacman video game and even clunkier uses for what joysticks the pyramid’s dwellers manipulated, yet here was Olsen nervously, perhaps embarrassingly, explaining that there was to be no pictures or recording devices inside the PAR, that we could not be more than six feet away from him at all times, and that we could ask any question we pleased but that we wouldn’t necessarily get answers.

Once inside, past two 7-ton steel doors, our ID’s were checked by a security Sergeant in camouflage, a 9 mm Barretta at his side. The photocopied announcement of a “Chili/Hot Dish cook-off (casserole)” was scotch-taped to the door of Central Security Control, where we were being “briefed.” They used that word.

A slow elevator took us to the third floor and the brain of the operation, the radar room. Before entering, Lt. Olsen picked up a phone and told whoever was inside that we were outside, getting ready to come in. He got an OK. Kate and I mentally high-fived each other. I was expecting a large, dark place with immense screens on the walls and several men absorbed in hushed concentration over inexplicably high-tech consoles of silent beeps and scrolling codes. I think so was Kate.

Here’s what we actually saw: A white neon-lit room the size of the average suburban living room occupied by three oversized, outdated, tan-colored but richly-scratched computer consoles that looked more Kaypro than Apple, the kind you might see in an air traffic control room of the early 1970s. We saw an entertainment center that included a nice-size TV, VCR, CD player and other enviable equipment, or pretty much what you’d see in any fire department’s lounge as the men and women wait for a call. We saw a fridge overstocked with every imaginable brand of soda and frozen, microwavable pizza, a microwave oven, a corner devoted to the “Phased Array Café” (boxes of Snickers, Butterfingers, Kitkat, Twix, Crunch), a magazine rack (Airman, Airpower, Smithsonian), and a few shelves with binders and booklets.

The words “Secret” or “Confidential” could catch your line of sight if you were careful, but the only secrets around were probably the stashes of pot and porn kept out of view of visitors. One wall was devoted to the kind of panel that showed arrival and departures in 1970s airports, except that instead of indicating Northwest Flight 5321’s arrival and gate, it indicated, in green, that we were at Defcon 5 (good news), and that a visible threat, Kate and me aside, was “not detected.”

At each of the three consoles a man sat looking at a large circular green screen that showed the North American continent crudely outlined in straight white lines. Other hap-hazard lines appeared with regularity — not missiles, but satellites. Scrolls of data listed the observed object launch point, impact, altitude, and range. When Kate asked Capt. Matt Degner, the 37-year-old missile crew commander on duty, whether the range was measured in miles or kilometers, Dregner said, “I believe it’s metric.” He didn’t sound so sure, which was not reassuring in case the Soviets or Chinese did launch something our way. Degner’s responsibility was to track missiles. Slow day.

The next console was manned by Jim Schwab, a 35-year-old crew chief in-training. He was tracking satellites. We looked at Mir’s path 250 miles overhead, a slow jagged line crossing the continent at 2,000 miles an hour just north of the Canadian border from west to east. That was about it for the nerve center of one of America’s 34 such early-missile warning systems. The men explained that their job was not to decide what to do about incoming missiles, but simply to tell NORAD under Cheyenne Mountain, in Colorado, whether any detection of missiles was a verified or false alarm. We did not ask why NORAD couldn’t link into the installation on its own, skipping the bored middle men.

It was rude to ask and a little unpatriotic, but I had to: Was this not outdated technology?

“All I can tell you,” Capt. Degner said, “is that they have punch cards back there that they still use.” In fact, all the programming at the site is done on punch-cards “back there,” in a much larger room dedicated to the actual computer that interfaces with the radar. The system, partly built by IBM in the late 1960s, is made up of 48 racks stacked up with old motherboards that look like airplane food trays.

Kate couldn’t resist asking Degner about Y2K, the computer catastrophe so feared at the time when the clocks would turn 00 with the new millennium. “PAR site. Computer 2000 problem?” she asked.

“Don’t go there,” He would intervene again when I asked the computer specialist how his 48 racks’ power compared with my laptop’s. And yet Olsen had just finished telling us how “this is really the cutting edge, this is where the Air Force is headed in the future, because space operations is getting bigger and bigger.”

For all our unease regarding the nuclear trigger, Kate and I left the site even more uneasy about the Jurassic feel of the technology. The poorest elementary schools I had once covered in the West Virginia coalfields had more advanced computers.

“It’s so Dr. Strangelove,” Kate said as we thanked Lt. Olsen, who’d nevertheless been quite patient with our two-hour visit. “Nobody who’s even played a video game in this decade could go, ‘Oh, wow, look at the setup over there.’ That place is an incredible museum of what computers used to look like.” But Dr. Strangelove was a funny movie, and the PAR site is not a prop. In 1980 at NORAD, ostensibly the nation’s “aerospace defense command,” a computer chip failure simulated an all-out Soviet nuclear missile attack. It took the officer in charge eight minutes to determine whether the attack was real, based on the sort of information fed to him by the PAR site. He was supposed to make that determination in three minutes. He was fired for taking his time, when he should have been given a medal of honor.

(Three years later MGM released “War Games,” the movie starring a teen-aged Matthew Broderick whose dial-up computer starts what looks like a thermonuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union, but is in fact the bored simulation of an artificial intelligence that was ahead of its time. In 2023, that time is now.)

With technology like what we saw at the PAR site, it’s a wonder we hadn’t blown up the world several times over. Maybe that’s what Olsen was so nervous about. He didn’t want us to see up close what the nation’s defenses really rely on. From afar, the military’s nuclear defenses look awesome, impregnable, heroic. In fact, they’re so prone to error and human stupidity that the last few decades’ averted catastrophes could be spliced together into a special episode of Jackass: Nukes Edition. It’s not because the military is particularly idiotic. It’s no more idiotic than any other military on earth. But Americans have a distinguishing faith in technology’s infallibility. How could a trillion-dollar infrastructure go wrong? That‘s the nation’s Achilles’ heel.

The military is full of Olsens who make sure the more aberrant stories of failures never get the headlines of chest-thumping servicemen chanting American supremacy at football games. But there’s only so much they can hide from unpatriotic journalist sons of bitches like Eric Schlosser, the author of Reefer Madness and Fast Food Nation who spent seven years reporting and writing Command and Control, documenting the hair-raising failures of the nation’s nuclear defenses and our “illusion of safety.” How about a few examples?

On Nov. 13, 1963, workers decommissioning Mark 7 tactical nuclear weapons in Medina, Texas, mishandled explosive spheres that rubbed together and ignited, setting off a fire that burned for 45 seconds before detonating 123,000 pounds of high explosives, demolishing the building they were in. The three workers had put enough distance between themselves and their mistake. The explosion didn’t go nuclear.

A few weeks later a B-52 carrying two Mark 53 hydrogen bombs with a yield of 9 megatons crashed into Savage Mountain, 20 miles from Cumberland in western Maryland. The two bombs were found in the snow. On Dec. 8, 1964, a B-52 carrying five hydrogen bombs with a combined yield of around 13 megatons crashed and burned on landing, damaging the bombs, but not igniting them.

The same week at a missile silo in North Dakota, two airmen mishandled a fuse check, triggering an ICBM’s misfire atop the Minuteman missile–a W-56 thermonuclear weapon with a yield of 1.2 megatons–that caused a section of the ricket to lift off and bounce off the walls of the silo. On Dec. 5, 1965, a pilot error on the USS Ticonderoga, an aircraft carrier, led to the loss of a plane, the pilot and a Marc 43 hydrogen bomb off the coast of Japan, none ever to be found. It could still explode, of course.

On Jan., 17, 1966, a B-52 carrying four Mark 28 hydrogen bombs, each with a blast power of up to 1.5 megatons, collided into a refueling tanker over the coast of Spain and crashed near Palomares, where three of the bombs were found. The fourth was never found. The Pentagon lied for a week, of course, claiming Spaniards were never in danger, and never disclosed that the fourth bomb was lost, until mobs around the U.S. Embassy in Spain forced the admission.

And so on. That’s a very partial list, and it doesn’t touch on the heart of Schlosser’s book–the 1980 explosion of a Titan II ICBM in Arkansas when the 9-megaton missile’s liquid fuel exploded inside its silo, sending flames 500 feet skyward, ejecting its warhead, killing an airman, injuring 22, and causing the belated evacuation of 1,400 civilians. The military, as always, insisted that all was well in the best of all possible worlds, because Pangloss has always been sure to build our infallible weapons with fail-safe devices.

And this was in the United States. I couldn’t possibly imagine what Russian clunkers and Chinese start-ups could be messing with through their potentially catastrophic trials and errors. We had made a nuclear tinderbox of the globe. Neither the Soviet Union’s decomposition nor China’s vertiginous rise were diminishing the hair-trigger, to say nothing of powers like India and Pakistan or North Korea and Iran, to whom nukes were crinkled manhood’s red Miata.

Nothing felt better than returning to Virginia’s kitchen and sinking my teeth in one of the diabetes-accelerants she had baked, a cinnamon bun in the shape of a missile silo’s dome.

*

“How was it?” Virginia asked, as if we had just returned from the movies. She knew we had.

Virginia herself had never been interested in visiting the PAR site. A waste of time, she called it, and “wasted moneeeeey. If you want anything done and done wrong, you get the government to help you, they’re good at it.”

My nuclear education began in 1981 as I read Jonathan Schell’s The Fate of the Earth the three successive weeks it appeared in The New Yorker. I remember reading at least two of the three installments in my older brother’s dorm room at Columbia University, because Schell was describing what would happen to Manhattan in case of a thermonuclear attack.

I could look outside the window at the metal fire exit stairs garlanding red-brick facades of apartment complexes filled with human beings and imagine it. “If you imagine that the bombs were distributed according to population,” one expert told Schell, “then, allowing for the fact that the attack on the military installations would have already killed about twenty million people, you would have about forty megatons to devote to each remaining million people in the country. For the seven and a half million people in New York City, that would come to three hundred megatons. Bearing in mind what one megaton can do, you can see that this would be preposterous overkill. In practice, one might expect the New York metropolitan area to be hit with some dozens of one-megaton weapons.”

Then again, I couldn’t imagine Schell’s descriptions of blast waves, of a city’s population irradiated, crushed, vaporized in moments, of “the ease with which virtually the whole population of the country could be trapped in these zones of universal death,” of fallout’s exterminating drizzle, of just “a republic of insects and grass” being left to roam the earth when all is done.

Around that time I marched in the only demonstration I’d ever joined in my life until then, the June 12, 1982 anti-nuclear march that drew 700,000 people in Manhattan, the largest public demonstration the city had known. Many of us genuinely thought our days were numbered. Ronald Reagan hadn’t made his joke about bombing Russia yet, but he’d done enough to convince us that Bonzo and Strangelove had fucked just before bedtime, and he was the offspring.

“The Day After” was televised in 1983 on ABC. That’s the 1983 movie that imagines a global nuclear war focused on the razing of Kansas City. Afterward Ted Koppel invited Henry Kissinger, Carl Sagan, William F. Buckley, Elie Wiesel, Brent Scowcroft and Robert McNamara to sit around a table and talk nukes. Gorge Schultz, the secretary of state at the time, spoke from his home, saying how the film was “a vivid and a dramatic portrayal of the fact that nuclear war is simply not acceptable.” Buckley said Schultz missed the point because “the whole point of this movie is to launch an enterprise that seeks to debilitate the United States.” Kissinger said the film presented “a very simple-minded notion of the nuclear problem.” Because nuclear explosions are so much more complex, especially when you consider the context–the treaties of Vienna, Westphalia or Versailles.

And on the men talked, rationalizing the irrational as if nuclear war was another issue to be debated around seminar tables and chat shows.

And then Wiesel, a survivor of the Holocaust who would later win the Nobel Prize for peace, said the only thing viewers could relate to: “Not being a nuclear specialist in any way, I’m scared, I’m scared because I know that what is imaginable can happen. I know that the impossible is possible. I have seen the film, and while I was watching it, I had a strange feeling that I had seen it before, except once upon a time it happened to my people, and now it happens to all people. And suddenly I said to myself, maybe the whole world, strangely, has turned Jewish. Everybody lives now facing the unknown. We are all, in a way, helpless, we are talking about nuclear arms, about the Bomb with a capital B, a kind of divinity in itself. Unless those who know militarily what it means, we readers, writers, people, we don’t know what it all means. When I hear about thousand bombs, megatons, I don’t have that kind of imagination. To me it’s an abstraction. But to me all this means is that the human species may come to an end, that millions of children may die.”

The scene I remember most from the movie had a woman at her kitchen sink, washing dishes one Kansas afternoon when, looking up from the suds and through the window, she sees the white streaks of several missiles that have just left their silos. In a glacial moment her eyes convey the horror without a blink. She understands. Death is here. It is no longer a matter of policy or deterrence or megatonnage or no-first-use promises. It is simply over.

Virginia Lillico also saw her neighborhood missile leave its silo. It was the first and only time she was to see a Minuteman’s shiny-white, 60-foot frame, a $7 million object then equipped with three 335-kiloton warheads, each capable of inviting a republic of insects and grass on three separate targets, back when the missiles were “MIRved,” or equipped with multi-pe-reentry vehicles, the euphemism for multiple warheads, the euphemism for genocide as rainstorm.

It was “up the hill” from the Lillico house. Trees would have blocked the view had it streaked off in time of war, while Virginia was washing dishes, as she probably would have done regardless of the alerts on television. As it was, the missile was just being shipped to another location.

“This one was put on a great big truck,” Virginia said, unable to remember the exact year the missile was removed. “That big thing was on a flatbed, and they took off with it. They hoisted that thing, they had a crane you wouldn’t believe. They were very careful. They said they didn’t dare bump it. We stopped on the road and watched. They moved it to Louisiana or some place.”

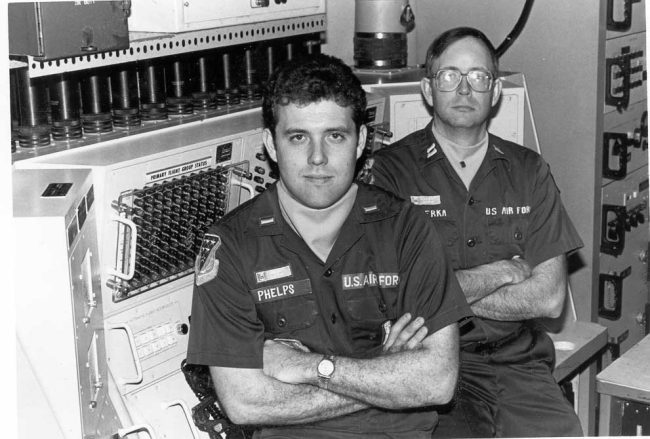

Several years after this piece first appeared in much different form, I got an email from Chuck Peterka, who’d just read it: I used to be one of the MCCC–Missile Combat Crew Commanders–who worked at ‘Bravo-Zero,’ the missile command site that controlled Bravo-10 through Bravo-19,” he wrote me. “I remember the place well. I’m the Captain in the photo… back in 1984 +/-, that’s me in the background on the right. I’m long gone from there and that, and thankfully so are the missiles of North Dakota. (We still have to worry about Montana, Wyo, Nebraska, but what the hey..)” He’d become a database engineer, working for the Vanguard Group in Valley Forge, Pa.

The Grand Forks missile field near the Lillico house was all emptied of its missiles in the early 1990s following a disarmament treaty between the United States and what remained of the Soviet Union. Three-warhead Minutemen were turned into one-warhead Minutemen and replanted elsewhere, or stockpiled at such places as Minot Air Force Base, a couple of hours’ drive from Virginia’s house, or at Barksdale Air Force Base in Shreveport, La.

The thawing of the Cold War has created the impression that the nuclear danger is over. If anything, it has increased. “In fact,” Brian Hall wrote in a piece called “Overkill is Not Dead,” “the end of the cold war and the attendant collapse of the Russian military have produced a situation in which the chances of a nuclear exchange have arguably never been higher.” We spend $25 billion a year to maintain a nuclear arsenal, maintain three active missile fields around the country, and continually upgrade and develop new weapons of mass destruction in an ongoing $1.5 trillion program.

Unlike a few decommissioned silos elsewhere — a Kansas silo has been turned into a house — the field around Virginia’s house is still hot, guarded military property. “They say they’re keeping them up in case they want to put something back in there,” Virginia says. “They go around and check those holes all the time. They’re maintained. The grass is cut.”

*

Virginia Lillico moved in with Kate in Jamestown eight years after I first saw her (I had visited her once in between), and died in 2011 of lung cancer, two days before her 95th birthday. The house and the land where I’d known her went to Conrad’s family, was eventually razed and a new house built on the same land but in a different spot. Virginia was buried in the Icelandic Hallson Cemetery in rural Cavalier County next to Kate’s father, who had died in 1963.

Virginia was one of the more remarkable people I met on my 15-month journey: we didn’t have much in common, but we bonded as if she’d known me all my life. It’s been the same with Kate. And to think that we owed it all to nuclear missiles.

Virginia lived the middle of a geographic irony, with the PAR site two miles in one direction, the latent missile field stretching for 150 miles in another direction, and, about 90 minutes’ drive to the west, the International Peace Garden.

The Peace Garden is a serene place that sits between the American and Canadian border, an irony in itself since it has been the most peaceful border of history’s bloodiest centuries (the 19th and 20th). The International Peace Tower, a multi-faceted concrete structure that was not built with elegance in mind, dominates the gardens. The tower was dedicated in 1983, the year of “The Day After,” one of the many peak-years of the Cold War. Half of it is on the Canadian side of the border, half on the American.

A few paces away is the Chapel of Peace, a non-denominational, square alcove of glass and marble walls etched with 59 quotes by the likes of Camus, Confucius, Dante, St. Matthew, Churchill, Einstein, FDR, JFK, Emerson, Gandhi, Lincoln, Plutarch… “I believe without a shadow of doubt that science and peace will finally triumph over ignorance and war,” goes Louis Pasteur’s quote, “and that the nations of the earth will ultimately agree not to destroy, but to build up.”

I would like to etch the 60th quote of the marbled walls, something Virginia had said about the men who control places like the PAR site and the missile silos, the men at NORAD and the men at NORAD’s Russian equivalent, in a place below ground called Chekhov. It’s as true today as it was when those thermonuclear-warhead-carrying planes were crashing, when ICBM silos were bursting in flames, and when, as in 2023, those 400 remaining missiles are being upgraded, spat on and polished with that obnoxious love we confuse with love of country while somehow forgetting about love of humanity: “I just hope they know what they’re doing.”

*

![]() 6

6

Robert Joseph Fortier says

Interesting story that I am happy to read and glad I did.

Joe says

Great writing too!

Concerned Citizen says

In the early days of my career in the Airforce I did a tour at Minot. This was during the late 80s and the Cold War was still very tangible. I remember the movie The Day After very well. Folks don’t realize how close we have come to that being a reality. And now here we are in 2023 reliving a similar scenario.

I remember one of the quotes from the Doctors washing after surgery. “Stupidity has a habit of getting it’s way.”

Geezer says

This series of articles helps produce more Flaglerlive habitués. (I had to use that word)

Why not collect all these articles and publish a book entitled “On the Road with Pierre?”

How about “Mr. Tristam’s Travels?”

I’d stick to printed books only—ebooks breed piracy. Why not self-publish a small run

in Palm Coast along with some book signings?

It begs the question: are there any bookstores left in Palm Coast?

Pierre Tristam says

All of the above are being considered, but as for bookstores, the only one left is that of the Friends of the Library, which actually just had a fabulous sale, grossing $2,440. It’s at the public library on Palm Coast Parkway. There is no full-time bookstore left in the city or in the county otherwise.

Pogo says

@Makes sense:

Considering the number of gun sellers, and other churches, that thrive in the Volusia/Flagler area.

Take it from the playgrounds and take it from the bums

Take it from the hospitals and squeeze it from the slums

All the kids make pistols with their fingers and their thumbs

Advertise a revolution, arm it when it comes

We’re cooking up the zeros, we’ve been doing all the sums

The judgment of this court is we need more guns…

Melt down all the trumpets, all the trombones and the drums

Who needs education or A Thousand Splendid Suns?

Poor is good for business, cut the forests, they’re so dumb

Only save your look-alikes and fuck the other ones

It’s the opinion of this board that we need more guns…

— Coldplay, Guns, 2019

https://genius.com/Coldplay-guns-lyrics

Ray W. says

Thank you, Pogo.

James says

https://flaglerlive.com/wp-content/uploads/virginia-lillico.jpg

When I asked- “Did you ever consider packing it all up and moving somewhere else… like to Florida?”

Suddenly the color came back into her face, and with a vigor and animation of a women a fraction of her age that I hadn’t observed in her up till then, she simply replied…

… “No f***in’ way sweety!”