By Jared Mondschein

The US Congress has had no shortage of viral moments in recent months. Senator Dianne Feinstein seemingly became confused over how to vote. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell experienced two extended “freeze episodes” during press conferences. And several members of Congress mistook TikTok for the name of a breath mint (Tic Tac).

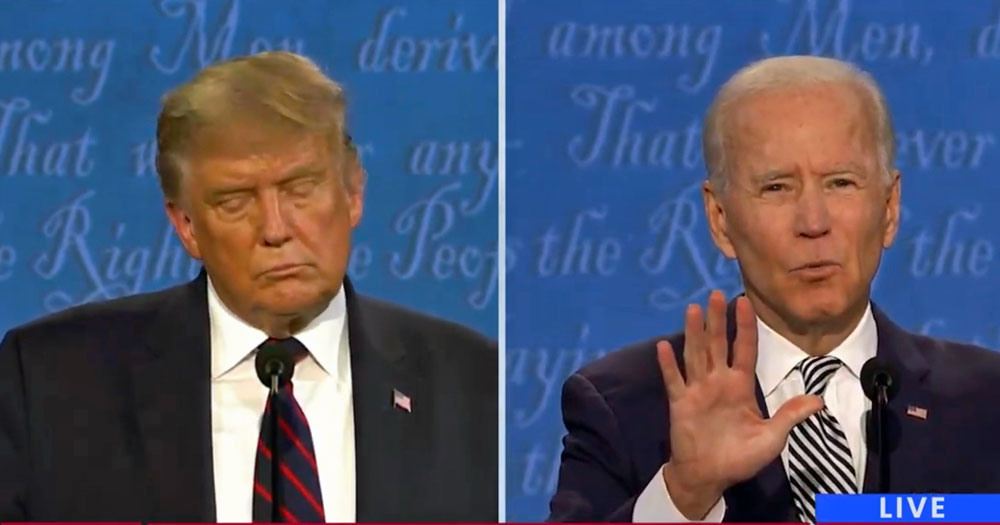

The world’s oldest democracy currently has its oldest-ever Congress. President Joe Biden (80 years old) is also the oldest US president in history. His leading rival in the 2024 presidential race, former President Donald Trump, is not far behind at 77.

Biden and Trump are both older than 96% of the US population. Unsurprisingly, they are both facing widespread questions about their ages and cognitive abilities.

How did we get to this ‘senior moment’?

America’s increasingly geriatric political leadership is not a surprising phenomenon. As the authors of the book, Youth Without Representation, pointed out earlier this year, the average age of US members of Congress has consistently risen over the past 40 years.

Some of this shift can be attributed to actuarial realities: much like the ageing US electorate, American politicians are living longer and fuller lives in old age than they did before, particularly compared to the time of America’s “founding fathers” (many of whom were under the age of 40 when the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776).

Some of this may also be attributed to older Americans being far more likely to vote than their younger counterparts. In 2016, for instance, nearly three-quarters of eligible voters over the age of 65 reported they had voted, compared to less than half of those aged under 30. And those older Americans may prefer electing politicians closer to their age range.

Yet lifespans have increased around the world and the ageing of US politicians still stands out compared to other developed nations. The average age of government leaders in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has actually decreased since 1950 – and today is nearly 25 years younger than Biden.

Florida governor and Republican presidential hopeful Ron DeSantis said the country’s founding fathers would “probably” implement maximum age limits on elected officials if they “could look at this again”. But this raises the question of why they didn’t do it the first time.

What did the founding fathers think about term limits?

The founding fathers fiercely debated term limits for both presidents and members of Congress and even included them for members of the Continental Congress in the first Articles of Confederation. However, they ended up not being written into the Constitution.

As much as Americans cherish the idea of the nation being founded on a constitution and laws instead of traditions and monarchy, the founding fathers ultimately did not legislate any term limits. Instead, they largely assumed custom, tradition and democratic elections would dictate the terms of office.

In fact, the first president, George Washington, helped begin the custom of a president not seeking longer than two terms in office.

Mirroring Cincinnatus, a Roman leader who became legendary for being given dictatorial control over Rome during a crisis but then voluntarily relinquishing control once the crisis was over, Washington left the presidency after two four-year terms.

For more than a century after that, US presidents adhered to Washington’s convention (which historians contend that Thomas Jefferson, America’s third president, in reality ended up setting) and did not serve a third term in office.

The first to break that tradition was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who won four terms in office, including a third just before the second world war. After he died in office at the age of 63, Congress ratified the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution that limited presidents to two four-year terms.

While US presidents have faced term limits for most of the past century, members of Congress continue to serve as long as they like. (There are currently 20 members over the age of 80. Feinstein, the oldest at 90, has served six terms as a senator from California.)

Part of the reason for this omission may be that the founding fathers and early American leaders did not expect members of Congress to stay in office as long as they now do. In the years after the Constitution was ratified, members of Congress simply did not seek re-election as frequently.

For example, the average length of service for US senators has more than doubled from about 4.8 years back then to 11.2 years today.

The price of elected office and who can afford it

Beyond demographics and changing habits of US politicians, one underestimated contributor to America’s increasingly elderly political leadership is that running for political office in America is more expensive than ever.

The 2020 election was not only contentious, but it was also the most expensive in US history. It cost more than US$14.4 billion (A$22.5 billion) for the presidential and congressional races – more than double what was spent in the 2016 elections.

The 2022 elections also broke a record for spending in a midterm election at US$8.9 billion (A$13.9 billion).

On an individual level, the average winner of a House of Representatives race in 1990 spent around US$400,000. By 2022 that had risen to US$2.79 million. The average winner of a Senate race in 1990 spent nearly US$3.9 million, compared to US$26.5 million in 2022.

It should come as no surprise that the ten most expensive House and Senate races in US history took place in the past five years.

Those with the resources necessary to afford such expensive campaigns are more likely to be older than not. Whether it be independently wealthy business owners or well-established politicians with extensive fundraising networks, the high cost of admission for political office undeniably favours the old.

In an era of extensive polarisation, it can often seem like Americans cannot agree on much. One area of agreement, however, is that their politicians are simply too old.

Yet while a majority of Americans may tell pollsters that, most still consistently end up voting for a candidate who is considerably older than them. That will very likely be the case again in the 2024 presidential election. At least one of those probable candidates (Trump or Biden), though, will be barred by term limits from being on the ballot again in 2028.

![]()

Jared Mondschein is Director of Research at the US Studies Centre, University of Sydney.

Pogo says

@FWIW