The U.S. Supreme Court court on Monday said it will not take up the Florida International University faculty’s challenge to a Florida law that bans travel to Cuba at universities’ expense. The court also declined to hear a death penalty case rising out of Daytona Beach, and involving a man with an IQ his lawyers said was too low to make him eligible for execution. In a third Florida-related case, the court also refused to settle a decades’ long water war between Florida and Georgia.

Without comment, the nation’s high court refused to consider the cases, which were among dozens of other appeals that were rejected Monday by the court, which takes up about 1 percent of the cases it is asked to rule on.

Travel to Cuba: In 2006, the Florida Legislature passed a law restricting travel to Cuba. The law restricts the use of state money for travel by state employees to countries that the federal government has listed as “State Sponsors of Terrorism.” Cuba has been on the State Department’s list of state sponsors of terrorism since Ronald Reagan placed it there, in 1982, though Cuba hasn’t sponsored acts of terrorism in decades (and had not been sponsoring such acts even then; Iran, Sudan and Syria are the three other state sponsors of terrorism, according to the State Department).

The Florida International University faculty senate and individual professors challenged the law, contending that it improperly infringes on the federal government’s power to make decisions about foreign policy–and disputing Florida’s interpretation of restricted travel to state sponsors of terrorism. “Travel to countries identified as state sponsors of terrorism,” they wrote in a brief to the court, “is not restricted as a consequence of their federal designation, and indeed is expressly permitted under other legal or regulatory provisions—either as a general matter (with respect to Iran, Sudan, and Syria) or under particular circumstances (with respect to Cuba).”

The 11th U.S. Circuit upheld the law. In their own brief to the Supreme Court, state attorneys wrote that professors are “not constitutionally entitled to demand state support for their academic travel simply because federal law permits such travel.”

The 11th circuit agreed. “We presume that the State can validly legislate on spending and on education matters,” the court wrote. “But we accept that, if a conflict with federal law or policy were plain enough, even these traditional state concerns could be overridden. We, however, do not see the Act as clashing sharply with federal law or policy. We conclude that the Act’s brush with federal law and the foreign affairs of the United States is too indirect, minor, incidental, and peripheral to trigger the Supremacy Clause’s — undoubted — overriding power.”

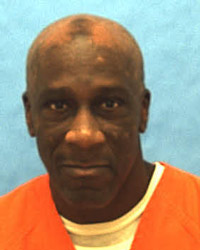

In May 1981, Ted Herring shot and killed a convenience store clerk during a robbery in Daytona Beach. Herring was subsequently tried and convicted of armed robbery and first-degree murder. A jury recommended the death sentence by an 8 to 4 vote (Florida is among the rare states where a unanimous verdict is not required in a capital case.) The judge went along, citing Herring’s previous conviction on a violent felony and that the murder was cold and premeditated, committed to prevent arrest. Herring, the court also acknowledged, had a difficult childhood and suffered from learning disabilities. He was 19 at the time.

But after four IQ tests, the circuit court vacated the death sentence because all four tests showed Herring’s scores in the 70 to 74 range, consistent, according to the circuit court, with a diagnosis of mental retardation. The Florida Supreme Court disagreed: mental retardation, according to the court, has to be more severe–falling below 70–to prevent the death penalty.

Herring is one of 402 people on death row in Florida. Two inmates have been executed so far this year: Robert Waterhouse and David Alan Gore, both of Pinellas County. Florida hasn’t executted more than two people in a single year since 2006, when it executed four.

Water war: The Supreme Court’s silence also leaves standing a lower court ruling over water flow in the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River basin, an interconnected system linking Lake Lanier north of Atlanta to the Florida Gulf coast.

Specifically, Alabama and Florida contend that federal officials did not have the authority to divert more water to Atlanta than limitations set out in a tri-state compact drafted back in the 1950s.

The fight targeted the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ control over the Buford Dam, which not only holds back the water that is now Lake Lanier but determines the water flow to the river systems farther south.

Georgia argued the water needs of the teeming city outweigh the minimum flow requirements. Further, as operator of the Buford Dam, the Corps has the flexibility to open the tap to the Atlanta area without an act of Congress, the state says.

Alabama and Florida officials said the Corps was charged with maintaining water flow needed to generate power, navigate the rivers and provide enough water flow for Florida’s commercial seafood industry.

The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta had said the Corps was within its purview to allocate water resources to the Atlanta area, and with Monday’s decision by the high court not to take the case, that stands. The cases, combined, are Florida et. al. v. Georgia et. al. and Alabama et. al. v. Georgia et. al.

–FlaglerLive and News Service of Florida

Leave a Reply