Saturday marked the opening of the Flagler County Art League’s third annual Best of the Best Show, a celebration of over 100 award-winning pieces from the league’s 2011-12 season. The show continues through July 11th.

Whatever is your definition of art, Best of the Best likely satisfies it, from the symbolic or abstract to the cathartic, the socially engaging, the decorative or aesthetically pleasing.

Best of the Best isn’t judged, but because it takes from all the shows that were judged over the season, it escapes the provincialism of themed gallery shows. Nor are future “Best of the Best” shows likely to be judged. Bob Ammon, the league’s newly named gallery director, there’s no talk of future juried Best of the Best of the Best shows. “I just don’t know how it’d add anything. Plus it doesn’t cost anything to enter so it’d be difficult to give money prizes.”

Incidentally, on the same night, across the way at Hollingsworth Gallery, was the opening of a singularly dark, demanding show—a retrospective of the paintings of Richard Schreiner, who gives Palm Coast an idea of what it would have looked like had Goya and Francis Bacon retired here. By contrast, “Best of the Best” is sinecure to the eclectic.

Photographer Kathleen Warren for example, who came to Palm Coast in 1995 to teach Biological Sciences at Daytona State College, became “hooked” on taking pictures after finding herself in a photographic darkroom (remember those?) in high school. Now she says her camera is never far away, catching a wide range of subjects skillfully processed in some instances into photographic art.

In “Dual Racers,” Warren shares one of her passions in an image of two Standardbred harness race horses dueling forward, synchronized, towards one jockey’s glory. Background elements have been dissolved through Photoshop manipulation to keep the viewers’ eyes on the horses, the way they would if they were actually watching a horse race. Warren owns horses herself so the challenge of successfully capturing the dichotomy between the elegant gracefulness with the juggernaut physics and physicality of thoroughbreds came naturally.

Like “Dual Racers,” Warren’s other work on display uses manipulation in a more personal or spiritual way. In “O, Israel,” “Boy at Western Wall,” and “Bread Man,” she shows her interpretation of the Jewish people in their natural biblical setting, which she experienced on what was actually a Christian voyage to the Middle East in December 2010-January 2011. “The largest piece, ‘O, Israel,’ has symbolism from the past, present, and future of Israel, while the other two small images represent people I noticed while in Jerusalem,” she says.

Entering into the world of three-dimensional art, we have the work of J. D. James. In this case, it’s an opulent molding of the head of Cleopatra, this one modeled after the Elizabeth Taylor enactment. James and his wife, who moved to Palm Coast from Columbus Ohio, started their own cookie jar pottery business after arriving here. “We are self taught in our artwork and we consider the cookie jar to be a work of art that was butchered in the potteries of Ohio,” James says.

Beaulieu’s painting, “A Walk in the Woods” –winner of the Best of Show Award in the league’s Spring Show—is a striking horizontally oriented composition painted across a panel. A dirt path of warm hues beckons the viewer through a forest clearing. The scene could be happening in real time or it could be just a flashback. “This was a small wooded area in my backyard in Massachusetts,” Beaulieu says. “Many an evening I would watch as the setting sun sent its dappled light through the dense foliage to the woodland floor below. And the white birch trees would echo the evening sun’s warm luscious colors.”

In “Pine Lakes Sunset” and “First Snow” which also appear in the show, we get to experience again Beaulieu’s sensitive and expressive relationship with landscape that is dear to him. In “Nathalie,” however, he takes his delicate painterly application into a figurative study just as seamlessly. A “beautiful young Haitian woman,” Nathalie is a friend of the Beaulieu family, and a source of inspiration to Beaulieu because of her efforts to earn her citizenship, learn English, and exceed in all areas of her new American life.

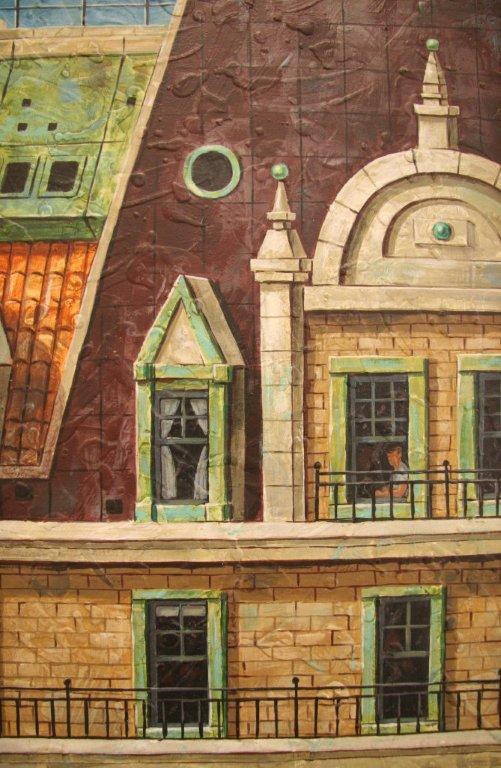

A painter of another type entirely is Gene Beinert. In his acrylic “Window World,” we’re brought into a very different type of environment with his representation of a lone but somewhat gothic and ornate brick building. It’s Beinert’s interpretation of New York City’s inexhaustible openness. The edifice depicted came from a photograph taken from the roof or through one of the top floor windows of a small advertising studio where Beinert had worked decades earlier. He didn’t paint it until years later. “One time, I heard a gunshot and looked down from my window and saw a man running for the subway,” he says, encapsulating the sometimes vertigo-inducing experience it is to be in New York.

In a unique employment of materials, Beinert threw some type of paste onto the masonite surface before he laid a stroke of paint. The effect is an enigmatic textured surface that, after you look at it for a while, creates the sensation of peering through a rain-flogged studio window.

A lone and contemplative figure can be seen in one of the small windows. It could be either Beinert, himself, or maybe someone he’s looking in at from his own building. Beinert served in the Pacific during World War II and attended Parsons School of Design on the G.I. bill after his discharge from the Navy in 1946. There he studied advertising. It wasn’t until years later that Beinert, now 88, picked up a paintbrush, after years of sketching and doodling.

On the other end of the age spectrum at the league’s show is Steven Sobel, who turns 31 next week. Sobel’s family came to Palm Coast from Clearwater in 1998. Before that, he, too, was from New York City. He graduated from University of North Florida with a degree in history in 2004. He’s always loved taking pictures on vacation but only got serious about it this year when he joined the art league. That hasn’t stopped him from snatching up all kinds of awards from some of his more experienced competitors.

Sobel’s other works in the show, “The Dragon’s Perch” and “Hoverfly,” capture wildlife of another variety: in this instance, hyper-realistic insects making their close up debut amid their daily toils. “In Wildlife photography it can be really hard to find interesting subjects; other than birds, squirrels, and deer we don’t have much locally,” Sobel says, “but there’s an entire ecosystem of interesting life living right outside everyone’s house and they pretty much ignore it—except when it comes to getting their blood sucked or contamination of their food!—because it’s too small to see clearly.” With a much-appreciated macro lens, Sobel seems to have solved this problem, for himself at least, and for the time being, he seems to be done with his degree in human history.

With “Storm over Canyonlands,” Sobel landed an almost alien landscape into the show. The environment is actually Utah’s Canyonlands National Park. The photo was taken during a road trip from Utah to Colorado with his father this past summer. Unlike Sobel’s other subjects, there’s noticeably no life forms of any kind in the frame.

One could go on and on, as this year’s “Best of the Best” had more entries than ever, says Ammon. “Well this year we upped the number of pieces that we’d allow people to submit. Before we allowed no more than two or three pieces, but this year we allowed up to four. Looking through the winners list we saw so many great entries. This year was the strongest ‘Best of the Best.’”

The rise in quality might induce skepticism. After all, what reasons could there be for a sudden, capricious leap of technical proficiency or talent? Ammon’s answer: “When we were doing only two shows a year, people weren’t being as productive—they’d only have to paint two times a year and that was it. Now they have to put something out almost once a month. They’re getting a lot more practice.”

![]()

Leave a Reply