A scheduled 90-minute visit by Sen. John Thrasher at Flagler Palm Coast High School this morning stretched to almost double the time as a normally placid meet-and-greet type tour turned into a hard-edged work session local school officials calibrated carefully to illustrate the gap between the Legislature’s assumptions about education and the everyday reality on the ground.

Whether discussing the mechanics of more flexible local rule-making, spiritedly debating with a school board member whether Gov. Rick Scott’s infusion of $1 billion into public education this year was “new” or “old” money merely restored, or kicking a ball with fifth graders at Phoenix Academy, Thrasher appeared engaged throughout, especially as local officials, rather than turn the visit into a whining session, attached actual solutions with every problem they outlined. Thrasher said he would take those proposals directly to Senate staff while encouraging district officials here to pursue the initiatives.

“Madame superintendent I want to tell you this in front of this guy,” Thrasher said, pointing to a reporter as the group sat down for a debriefing two hours into the tour, “and I’m not blowing smoke at you: this is the best school tour I’ve ever had, by far. By far.”

He did not specify beyond speaking of the detailed attention in presentations by FPC Principal Jacob Oliva, Superintendent Janet Valentine, School Board member Colleen Conklin, and—what seemed to bring out the most twinkles in his tired eyes—the staff and students at Phoenix Academy, the experimental, 65-student elementary school set up astraddle of FPC’s campus with an old school board building.

Three ideas to explore legislatively or problems to solve interested him the most.

First, at the outset of the tour, FPC Principal Jacob Oliva described to him the unintended consequence of scheduling end-of-course exams five weeks before the end of the course. The exams make a lot of sense, the principal said, “because they’re assessing a content that the student was in, so if a kid takes algebra, they’re going to take an algebra end-of-course exam instead of a grade-level specific exam. But the way the assessment works out, a lot of these students are being tested four to five weeks before the semester is over, so we run out of time for the teacher to really get in depth and cover the material to the level that it needs to be covered before the student takes it. And just the amount of time it takes to give the assessments, because we have to pull kids from classes to get them on computers to take the exams. It interrupts the instructional time for all their classes. So it’s a good concept to have the end0-oif-course exams, but the way we have to administer them, because of the calendar and how long they take, it makes it a lot more challenging.” It’s not clear why the state doesn’t allow for the tests to be administered at the very end of the school year.

Second, Thrasher appeared at least willing to listen to the problems created by the new teacher evaluation system, and conceded, when asked point blank, that the end result—an overly complicated formula that combines standardized testing results with all sorts of other factors—was not quite what the legislation set out to create. It’s difficult to imagine Thrasher moving away from a merit-pay system the Legislature made one of its priorities, however unwieldy the consequences, but he sounded genuinely interested in “tweaking” legislation to make the system less onerous.

Third, Thrasher—always a friend of charter schools—was interested in an idea Conklin pitched in the form of giving the district more authority creating schools like Phoenix Academy (where students enter in fourth grade and stay with the same teacher in in the same group through sixth grade in their core subjects.)

“If we can create something that would be similar to a charter school now, what would be the difference? The difference is flexibility.” Conklin said. “Flexibility in, say, a charter school has the flexibility of curriculum, a charter school has the flexibility of calendar, schedule, all of those regulations are kind of lifted. But the other thing is, too, they’ve accessed some of those charter dollars that are huge.” Particularly construction and planning dollars. Conklin’s and Oliva’s idea is to use the Flagler school district as a pilot to allow the district to develop its own charter school built around a curriculum with FPC’s flagship Community Problem Solvers program at its core.

“We’ve worked with the problem solving community to get their endorsement,” Oliva said, “we’re working with all these people to get their endorsement, and we want to be able to set it up kind of as our own school, and then we hit a bunch of roadblocks.”

Conklin explained: “We need to be completely free from the teachers’ contract to do some of the things we’re talking about doing, and the flexibility to really develop a brand new schedule. I mean, talk about breaking the mold. These guys have some really great ideas, and the fact is, we need some planning dollars and they’re just things we would need very much like a charter school needs.” Conklin had provided a print-out of the district’s shrinking finances in the past four years.

At that point, Thrasher mentioned Patricia Levesque, the executive director of the Foundation for Florida’s Future—the Jeb Bush-led conservative organization at the source of broad, often radical education reforms in a dozen states, Florida included, that emphasize standardized testing, online schooling, charter schools and the channeling of public dollars toward private schools, all usually at the expense of the traditional public school model. Conklin, who does not usually see eye to eye with Thrasher on most issues, was taken aback by his dropping Levesque’s name, but he did so immediately after Conklin had mentioned money: in other words, don’t look to the Legislature for more of it.

It was a subtle but pointed reference, made less subtle a bit later during the debriefing when Thrasher mentioned the $1 billion n what he called “new” money Gov. Rick Scott asked—and got—for education.

“The good news, if there is good news, we did $1 billion new dollars this year. Granted that was catch-up money—”

“You mean old?” Conklin interrupted.

“A billion new dollars,” Thrasher persisted, after a moment’s hesitation.

“Of old, old dollars? OK,” Conklin, herself persisting, went on.

“Well, old, however you define it,” Thrasher said.

“We’ll take it,” Conklin said, laughing.

“Well, if we hadn’t put it in there, there wouldn’t have been any, right? We’d have been where we were. So $1 billion new dollars.”

The exchange, obviously unscripted and unexpected, was revealing of the tension lawmakers and the people at the receiving end of their laws often deal with, but seldom with a chance to address it face to face. Diverting the exchange to better news, Thrasher then spoke of economic indicators now pointing in the right direction, suggesting that tight budgets might become less so in coming years. But even those economic indicators are uncertain, as the last two months’ job reports and the last quarter’s economic growth report—all more modest than predicted—showed.

Thrasher did not leave off without making additional points about money, saying the Legislature had changed class-size rules to give schools more flexibility, and was seeking to chance wording in the constitutional amendment about class size. But, and here he did what Republican lawmakers now do almost reflexively, the unions wouldn’t let it happen. “You know, our friends in the Florida Teachers Association, or whatever they call themselves,” he said derisively—it’s actually the Florida Education Association—“were all against it, all the liberal groups, I’m not, I’m just saying. The unions, everybody—I wanted to try to do something about it. I wanted to modify it. Now we’re stuck with a provision in the constitution and we’re trying to work around it statutorily as best we can.”

When the conversation turned back to the charter school concept Conklin and Oliva had brought up, Thrasher was more interested.

“I get it. I like the concept, and I will look into it, and you look into it with Wayne,” Thrasher told Conklin, referring to Wayne Blanton, the executive director of the Florida School Board Association who has some influence in pipelining legislation to Tallahassee. “The charter idea I love, I really think we need to pursue that,” he said later.

Two elements of the visit made a deep impression on Thrasher: his conversations with FPC’s Community Problem Solver students and their teacher (Diane Tomko), who were working in the school library, and his walk through Phoenix Academy entirely in the charge of three fifth graders, who guided him, told him where to go, what to listen to, and what to see, from math and language arts classes to their green and recycling projects, their rabbit and their vegetable garden and chicken coop. Ironically, Phoenix Academy was one of the programs the district listed for elimination last year as part of its cost-saving measures. The possibility drew out the Phoenix Academy community–students, teachers, parents–in droves of pleas before the school board. The board backed off.

“We believe we represented the district in a favorable light and hope we shed some light on the needs of our schools,” Sue Noble, a teacher at Phoenix–and one of its leading advocates–said, speaking of schools in the plural, not just her own, “needs which increase exponentially with every cut. Now, when he considers legislative action, he will be able to put a face and a story with the potential outcome.”

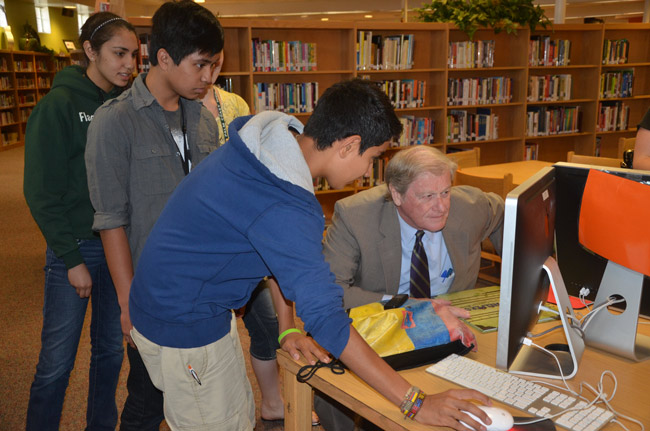

In the library earlier, Thrasher was engrossed in two separate conversations with problem solvers, who outlined the projects they were working on and were able to show the senator their work in action—including a project providing a live, web-based calendar of teen-related events around the county (with a coming phone app).

Thrasher also got an extensive tour of the school’s fine arts areas—the auditorium with Lisa McDevitt, its director, John Seth’s band program, Amy Fulmer’s choral zone, where a small group performed Dave and Gene Perry’s “The Cuckoo” for him, and Edson Beckett’s graphic design class, source of some of the school’s most creative works over many years (Beckett’s own included). He also got an earful about the 250-student Flagler Youth Orchestra the district supports as part of its commitment to the performing arts. At every turn, Thrasher introduced himself to faculty or students as John, bantered at ease and seldom gave the impression, as politicians and physicians so often do, of having to be elsewhere. He was in the moment.

“Here’s what personally I’d like to have come out of this,” Valentine, the superintendent, told Thrasher at the end of the visit. “You know our faces now, you know who we are. As we see solutions to some of these things, we will send them to you guys—”

Thrasher, interrupting Valentine, invited local district officials to pepper his office with calls and follow-ups. “What you gave me today, some problems and solutions, those are things that I can discuss with the staff of the education committee, because the staff doesn’t change,” Thrasher said. He added later: “Hearing from them gives me a chance to go back and look at it, see if we need to tweak and refine some of the things that we’ve done, and that’s why you do this,” Thrasher said.

The visit was not entirely apolitical, as those things seldom ever are: Thrasher, who was accompanied by one staffer who doubles up as a campaign aide, is running for re-election—as is Conklin—and Thrasher’s senate district now includes all of Flagler County. It previously included a plurality of it. But the visit was planned as far back as the fall, Conklin said. Conklin, who is the school board’s legislative liaison, had made a presentation to the state School Board Association, proposing that all local districts involve their legislators in on-the-ground visits similar to those board members and school staffers conduct in the Capitol once a year. Thrasher’s visit to FPC was eventually scheduled for this week, to coincide with Teacher Appreciation Week.

There is no process in place right now for a school district to be in the game of education reform and develop its own charter,” Conklin said. That’s why the agenda for Thrasher’s visit had included a line about the Legislature’s need to look to districts for reform pilot programs, and why she was asking him to “put us in, coach,” in the reform-education movement. Just then, Thrasher kicked a yellow ball on the playground at Phoenix Academy, sending it looping high above the playground, and, unintentionally, lobbing down near Conklin.

“He took a lot of time, he didn’t rush it, I’m very grateful,” Conklin said after the senator had left campus.

ol'sarge says

finally some good press for this county’s embattled teachers…thanks, FlaglerLive!!

Will says

The day looks like a winner for School Board member Colleen Conklin! It’s great that she’s so active and up to speed with state issues to help something like this happen. Compliments should go too to Senator Thatcher for making time to participate, listen and learn. Too many visits like his are walk-throughs with a wave.

Sue Dickinson says

Great job to all of you invovled in todays visit. Flagler County’s voice for the second time in just the past few months has been heard by our Legislators. Very impressive.

Parent of 2 says

This is great press for the district. Hopefully he tries to implement some of the ideas the staff had.

I would like to make a note at Dickinson’s comment. She tends to only see things when they are positive.. She avoided the whole issue of uniforms, which the majority of parents do NOT want.

Liana G says

But, but … look at the kids, none are gullible victims of sophiscated corporate advertising and branding. The CEO of American Apparel said recently something to the effect that this generation isn’t artistic or creative. They’re copycats and followers. The guy has soul. But I still wouldn’t buy his overpriced sweatshop labor merchandise.

Sue Dickinson says

I am sorry you thought I avoided the uniform issue. I have been in favor of uniforms since 2007. I still beleive that with some time it is going to end up a serious positive. Please just give it a chance. Thanks

Liana G says

Ms Dickinson, I am of the opinion that you made a very good call on the uniform policy. Thank you. Often times we, the general public, are unaware of the underlying issues that result in certain decisions. People are naturally resistant to change. We are creatures of habits, couple with our fear of the unknown. It is a “serious positive”, but don’t expect everyone to agree even when they do see it. That’s just another one of those human nature flaws.

KS says

I am not a fan of Sen. Thrasher, but I am impressed that he finally spent time trying to understand the true workings of a public school. Truthfully ALL government officials, from the local to national level, who make such drastic decisions that effect our children need to start spending real time at real schools, seeing the truth. They need to be spending quality time in our schools, with the real stakeholders; students, parents, and teachers, instead of rubbing elbows with lobbyists from testing companies and for-profit charter management companies. Thanks for taking the first step in the right direction Senator Thrasher! Way to go Flagler Palm Coast High School!

JohnPC says

I am surprised at the gullibility of the readers of Flagler Live. This is the man who is in Jeb Bush’s pocket and has led the charge to destroy public education in Florida. Anyone who believes that this leopard has changed his spots after one visit to the den of his prey is either incredibly naive or a fool. Now that all of Flagler County is in his district, he is saying whatever he has to say to get himself re-elected so that he can continue his assault and finish what he has started. If he is re-elected, these “ideas” will suddenly become frivolous or irrelevant. Wake up and smell the coffee people!

Liana G says

Funding. Funding. Funding. When our system was rolling in dough, these same folks were still screeching about not enough funding even when they were diverting the money to increase already fat salaries that made no positive impacts on education. The results were dismal then as they are today (the News Journal did a fantastic job posting ALL the salaries of gov’t employees in Flagler County and elsewhere).

I recently read two rather troubling articles. One had to do with a prominent high school currently being investigated for graduation inflation rates. It seems that while students were graduating in high numbers at this school, their college readiness scores were not reflecting their graduation success. I wonder if an investigation into our high school graduation rates would come up with the same findings.

The second article had to do with the firing of the Long Island District Superintendent and Asst Superintendent over scholarship irregularities. Apparently students were receiving scholarship to Cornell and other colleges that sent up red flags. The article didn’t get into exact details of how this was done, so curious me went to a high ranking college official for help in finding out more. What I found out was that it was another case of grade inflation. School officials would again tamper with students grades to get them into colleges. This was not done for the benefit of the student (according to research most of these students end up dropping out), but to feed the egos of the folks tampering with the grades. Fudging grades just to make themselves look good and providing them with bragging rights! Didn’t they think they would get caught? Stupidity and nihilism at its finest!

BTW, why is BTES losing so many of its students to Imagine? Are parents in better financial positions /better educated more in favor of school choice?