The results of Flagler County’s only—and therefore most consequential and historic—election of July 2017 are in: Baked potatoes, not French fries, are county residents’ favorite way of preparing the county’s emblematic crop.

That shocking result, left at least one Supervisor of Elections employee in disbelief (“I call for a recount,” said Bea Rush), and may have justifiably raised the specter of Russian tampering, particularly since French fries didn’t even rank second: mashed potatoes (like baked potatoes, a more common cooking method in the lands of Pushkin, Lenin and Putin) did.

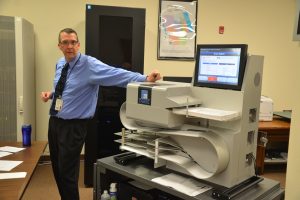

But part of the reason behind Tuesday’s mock election, Supervisor of Elections Kaiti Lenhart said, was to show voters not just where to slide their ballot, but how the voting system works, inside and out, and learn how voting machines can’t be tampered with from the outside: they don’t, they can’t, receive data of any sort. They only send. And the particular machine used on Tuesday, a brand new model showcasing Flagler County’s new, state-mandated $560,000 voting system, hadn’t even had to send any data: it spat out a printout of the results, none of it in Cyrillic, showing that baked potatoes got 28 percent of the vote, mashed got 19 percent, a stomach-turning tie with au gratin, with French fries coming in a miserable fourth, with 13 percent of the vote. In another sign that the results had in fact been tamper-proof, potato-based vodka got zero.

More than that: they each got a tour of the entire facility, as Lenhart said it was time to give voters a look.

“The whole idea is to bring you behind the counter because people come in here, they vote and they go home or they come to the counter, they register and they leave,” Lenhart told the very last group of the day, at close to 6 p.m. “Most people don’t know what happens behind the scenes, so that’s really the whole point is to bring you guys in, and for the transparency, which is so important, especially in light of recent news, negative news items, which undermine the trust in democracy. So if you don’t trust that your ballot is going in that box and [being counted], then I’m not doing my job properly. So it’s really for you all to build your trust in the process, and I haven’t had anyone come out from the tour today out of the hundreds of people that have been here that said, you know, ‘well I just don’t know what you guys are doing here.’”

The exercise doubled up as training for the office’s staff, and testing for the new equipment. (Lenhart allowed that cracks about Russian tampering was a day-long theme with visitors’ humor.)

Most people who have known much at all about the supervisor’s office over the past few years—as too many people have had occasion to know, chiefly because of the office’s embarrassing Dark Ages—may have been familiar with the then-infamous canvassing board room, a glassed-in coop next to a larger room where the board sits around a big table to examine or count certain ballots at election time. The tour ended there, with Ryan Kramer, the office’s IT coordinator, describing and using a machine that processes 300 ballots a minute, and where mailed-in ballots go. He stood in front of a relatively large, tall black box, its deeply tinted glass barely allowing a few faint computer lights blink through. That’s the office’s central nerve system, its server where all data passes through. It is locked. It is the office’s holy grail. You get the sense that if anyone touches it without the authorization to do so would face a fate similar to people less skilled than Indiana Jones to make it out of the Temple of Doom.

Speaking of which: that was just what the supervisor’s office had been until the Lenhart era opened it up, and though Lenhart did not say so—the current supervisor is as diplomatic and cheery as the previous one was not—one of the purposes of the open house Tuesday was to remind visitors that the office is a welcoming place in the service of voters. The open house, Lenhart said, was a first in the history of the office, which not so long ago was run on the North Korean model of government bureaucracies: you took your life, or at least your rights, in your hands when you stepped in there, where demeanors in the shape of daggers greeted you at the counter.

The final hour of Tuesday’s election drew, among the voters, County Judge Melissa Moore-Stens, Property Appraiser Jay Gardner (who, mysteriously, did not actually vote), School Board Chairman Trevor Tucker, Flagler Education Director Joe Rizzo, and former School Board member John Fischer, who was back after voting in the morning. The election also drew elections officials from Lake and St. Johns counties.

The election produced other results in what was, after all, a double-sided ballot.

In a couple of hokier categories added onto the ballot clearly to test the machine, blue was voted residents’ favorite color with 38 percent of the vote, quite a revelation in an increasingly crimson county (red got a forgettable 12 percent of the vote), and the Bulldog was voted favorite school mascot with 39 percent of the vote.

The complete results are below.

![]()

Mock Election Results (July 2017)

Click to access 2017MockElectionResults.pdf

snapperhead says

French fries would have won the popular vote if you discount the 3-5 million votes by illegal voters. #rigged election #fake media @ real Orange Julius

JM says

Definitely Russian meddling, just ask the fake media. Trump 2020

Ken Dodge says

While much was covered about new voter registration, nothing was mentioned about removing voters from the registry, as in relocation out of the county, or by death. I brought this to the attention of one of the staff and an informative discussion ensued. The Supervisor would do well to assure her constituents that all the bases are in fact covered as it would boost the public’s level of confidence.

palmcoaster says

Looking for the Supreme Court to end the current Gerrymandering and illegal voter suppression and Muller end the selling of America to Russia as appreciation for election interference.. Then we will really see who wins in 2020.By then maybe we have not to endure and laugh so much about the teinted twits.