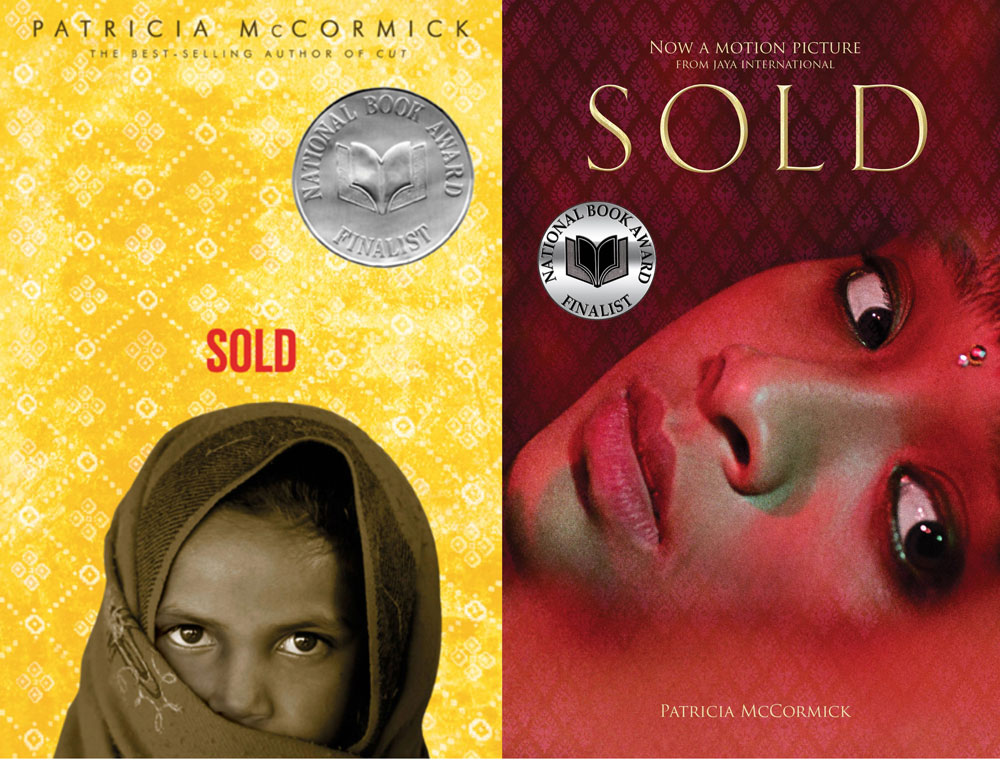

Patricia McCormick’s “Sold“ (Hyperion/Hachette 2006) is among the 22 books so far this school year that a trio of individuals have sought to ban from high school library shelves. The book-banners are basing their objection to Sold, as they are to all the books they’ve challenged, on allegations of inappropriateness plagiarized from a national website that published this report on McCormick’s book. A joint committee of Flagler Palm Coast and Matanzas high school faculty members voted to keep Sold on library shelves. The decision was appealed to a district review committee, which meets for the first time on March 6 at 6 p.m. at the Government Services Building’s Room 3A in Bunnell. (It is different from the school-based committee meeting Tuesday to review Melinda Lo’s Last Night at the Telegraph Club.) The district appeals committee will make a recommendation to Superintendent Cathy Mittlestadt on whether to retain or ban the book. If Mittlestadt decides to ban the book, the decision is final. If she decides to retain it, the decision may be appealed to the school board. The district has not resolved the legal discrepancy that gives book-banners the right of appeal, but not book advocates. The following review by FlaglerLive Editor Pierre Tristam is presented as a guide.

![]()

“My name is Lakshmi.”

“I am from Nepal.”

“I am thirteen.”

Sold, a 2006 National Book Award finalist, is the essential and beautifully written story of Lakshmi, the fictional autobiography of an untold number of girls and boys sold into sexual slavery around the world. She could be from San Salvador, from Turin or Atlanta.

Sold, a 2006 National Book Award finalist, is the essential and beautifully written story of Lakshmi, the fictional autobiography of an untold number of girls and boys sold into sexual slavery around the world. She could be from San Salvador, from Turin or Atlanta.

Patricia McCormick, an American journalist who describes herself as “a survivor of sexual assault” and Sold‘s author, imagines Lakshmi as a sweet, trusting peasant girl from Nepal’s Himalayas who gives the cucumbers she grows pet names, is the “number one girl in school,” and dreams of Krishna, “the boy with sleepy cat eyes, the one I am promised to in marriage.”

The family considers a tin roof a luxury among villages where children routinely die of fever, “the coughing disease” or because they couldn’t get to a doctor on the other side of the river. Lakshmi has lost four siblings so far. It’s good fortune enough to survive. Instead of money, “we linger over a luxury that costs nothing: Imagining what may be.” Lucky for Lakshmi, she has, like McCormick, a gift for observation.

In a numbingly patriarchal world, Lakshmi is close to her mother as she is not to her stepfather. She brings her stepfather tea in the morning and rubs his feet at night. He shares his tea-shop buddies’ derision for girls, even in her presence: “A son will always be a son, they say. But a girl is like a goat. Good as long as she gives you milk and butter.”

Lakshmi’s life will soon be reduced to something a lot worse than a goat’s. Her step-father is to blame. Her mother is not blameless.

Lakshmi’s mother is naive and, a universe removed from Gloria Steinem, painfully submissive. When her daughter asks her why women suffer so much, she tells her that’s how it’s always been. “Simply to endure,” she says improbably, “is to triumph,” a self-conscious statement at odds with the mother’s character. McCormick adds it as one of many bones to her American readers, the way she makes the trafficking parent a step-father, rather than a biological father, though in desperate families blood is more often the lubricant to exploitation.

When Lakshmi gets her period, it’s off to the shed, to endure the still-prevalent atrocity known as chhaupadi, a Nepalese word that implies a woman on her period is polluted. So it remains in some Nepalese regions, where girls and women spend the week around their period sequestered in sheds where they regularly die of cold, carbon monoxide poisoning (as they try to keep warm), or animal attacks. No triumph there.

Before tripping into holier-than-thou supremacism, it’s worth noting that similarly demeaning attitudes toward women on their period in Christianity, Islam and Judaism were and still are no better in lingering dungeon communities, though the practice seems as universal as misogyny: George Frazer’s Golden Bough is a catalogue of menstrual segregation from Galela to Sumatra to Uganda to America: “Among all the Déné and most other American tribes,” he wrote, “hardly any other being was the object of so much dread as a menstruating woman. As soon as signs of that condition made themselves apparent in a young girl she was carefully segregated from all but female company, and had to live by herself in a small hut away from the gaze of the villagers or of the male members of the roving band.” Closer to home, closer to our time, closer to Flagler, or in Flagler, there’s more than a few parallels between the banishment of “polluted” girls to huts and the banishment of polluting books.

When Lakshmi hears from the first of many deceivers of the possibility of working as a maid for a rich lady in a city, she imagines what may be, and wishes she could go. (“Where I live,” a woman who would be the American equivalent of a creepy ice cream truck lure tells her, “the girls have sweet cakes every day.”) She really thinks she’s going into domestic work when her stepfather sells her for a pittance to settle his gambling debts, and her mother gives her the rules of being a slave-maid. She can’t wait. Her stepfather, another deceiver, knows very well what he’s selling her for: “She has no hips,” the buyer tells him, knocking down the price to 800 rupees, something like $6.

Lakshmi’s observations as she travels across the border to India are a string of unknowing premonitions, creating a painful sense of irony for the reader. She has no idea. She’s the innocent child walking into the maw. “I am afraid of this city where the lying-down people look like the dead. And the standing-up ones, like the walking dead,” she says on arriving in what may be Calcutta, where McCormick did some of her research. She calls one of her traffickers “Uncle Husband,” her pimp is “Auntie,” she of the blackened teeth, and she thinks “Happy House,” the name of the brothel where she lands, really is the rich lady’s mansion she’ll be tending.

It’s not much later, after she’s been dressed up, made up, drugged and forced to be with an old man that she realizes she’s in hell and tries to flee. She rejects the old man, only for the violence to begin. This is not a story about sex but brutality. It is constant as “Auntie Mumtaz,” the house madam with all the elegance and kindness of an angler fish, methodically, sadistically tortures her into submission and reminds her with every beating that she’ll never pay off her debt to go home.

The sexual violence in comparison–the rapes–are barely alluded to in a couple of passages (“with a sudden thrust I am torn in two”) as Lakshmi after her initial, hopeless revolt learns to disassociate herself from the horror:

… men come.

They crush my bones with their weight.

They split me open.

Then they disappear.

I cannot tell which of the things they do to me are real, and which are nightmares.

I decide to think that it is all a nightmare. Because if what is happening is real,

it is unbearable.

McCormick’s description of the psychological disassociation is all skill and heartbreak as Lakshmi hears a steady thud she can’t place until she realizes it’s “is the sound of a headboard hitting a wall,” but doesn’t realize it’s her own, then she hears another sound she can’t make out until, with great effort, she figures out it’s “the muffled sound of sobbing.” It’s only when the rapist, called Habib (another irony: the name means darling) rolls off of her that she understands: “I was the person crying.”

It is also the most explicit part of the book, though the lines I have included here are the extent of it.

To think that book-burners would object to a passage like this suggests not only that they have the literary appreciation of dust mites, but that they would rather silence the voices of victims screaming for help in order to satisfy their claim to moral purity. The claim is a fraud, because it is complicit in an atrocity: In court, prosecutors always remind judges and juries that consumers of child pornography are re-victimizing children by getting off on the rapes depicted in images and videos. When book-burners want the voice of victims of abuse silenced, fictional or not, they are the traffickers’ pimps. They are keeping unknowing parents of child victims ignorant, they are keeping the trade going, keeping the abuse underground, enabling the Habibs of the world to go on raping in peace. The book-burners–these so-called “moms for liberty,” these morally polluted remote-control abusers who feign concern for children at school board meetings–are the guards at the whorehouse door.

Lakshmi alternates in the briefest of chapters between prose and free verse the way she confounds the reader–the way she is herself confounded–between shock and lyricism, between the inhumanity done to her for the price of a bottle of Coke and the humanity she clings to: “There is a moment, between the light and the dark, when the smell of frying onions blows in through the windows. All over the city, the cooking hour has begun. This is the saddest smell in the world because it means that here at Mumtaz’s house the men will start to arrive.”

The chapters are brief, at times no longer than a few sentences or verse, because her life is made of shards. Lakshmi’s story is those picked up pieces, jagged and cutting and glittering and rearranged as a testament to survival.

This is a harrowing, not a depressing, book. Lakshmi is too winning a character to be depressing. There is artistic license at work here: the implication that she may be an exception is in the suicide of another girl at Happy House and in the fate as outcasts that awaits many girls past their marketability. We don’t know if Lakshmi will survive. But I suspect McCormick was not a little inspired by Mattie Ross, the 14-year-old of Charles Portis’s True Grit to create the portrait of this girl who won’t be fooled. She may not even be the exception. McCormick did her research through survivors of the trade, who now lead the movement to battle traffickers.

So don’t call Lakshmi “endearing” or “adorable.” You’d be violating her like her johns, just differently. She becomes her own woman before her time, and like Ivan Denisovich or the prisoners of Dostoevsky’s House of the Dead who refuse to lose their humanity through the simplest acts of being human (like referring to each other by their names instead of their numbers), Lakshmi finds ways to salvage hers, through friendship, and most magically, through language.

Her friendship is with the young son of a house prostitute at the house who is lucky enough to still attend school, the boy she initially calls David Beckham because his shirt bears the soccer star’s number. The David Beckham boy’s name is Harish–the name means Lord Shiva or Vishnu, a Hindu deity–who teaches Lakshmi Hindi and English words like girl, boy and “how are you today.”

There is not a hint of eroticism in the book, least of all in the scenes of abuse. But to any lover of language, as Lakshmi very much is–she understands instinctively that language is life and liberation, it is her one accessible pleasure–the eroticism in her recitation of new words is palpable, even to her: candy, bread, cricket, pen, radio, chicken, remote control. “I love the way these new words feel in my mouth. Even if they are not true.”

And she learns those sentences–“My name is Lakshmi.” “I am from Nepal.” “I am thirteen.”–three sentences that, by the end of the novel, will leave you with an emotional jolt you will not have expected. They are Lakshmi’s Declaration of Independence.

So why a Nepalese girl? “I chose Nepal and India in particular because those are two countries that have made a lot of progress on the issue of trafficking,” McCormick told an interviewer. “There are a lot of NGOs [non-governmental organizations] working in both countries, on education, on prevention, on setting up stations at the borders, on rescuing the girls and rehabilitating them, that it made it much easier for me as a reporter to go in and find the people that I needed to talk to because of the hard work and the generosity of the people in Nepal and India who are doing the work on the ground.”

Which brings up a sore point with an otherwise critical and literary work. Sold suffers from a terrible case of white saviorism complex. The johns all seem South Asian. The saviors all seem American, as if western sex tourism weren’t a limitless pipeline keeping the brothels thriving.Even what documented facts are available point to western johns: “Since 2016, police have identified and arrested at least 12 tourists or international volunteers, all men older than 50, mostly from Western countries (Austria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, India, Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States),” a 2022 State Department report finds.

McCormick is drawing a bit from her experience: “I met a young man who was a photographer and I pestered him to death with questions,” McCormick told an interviewer, “and he said he was working as a photographer posing as a customer going into brothels to solicit the service of young girls. And then he would take their pictures and document that they were there and get that information out to the rescue groups. I was stunned. I didn’t know that such a thing was happening.”

The man who attempts to rescue Lakshmi is one such American with a camera. But her own author’s note states it’s the survivors of the trade in local organizations that are having the greatest impact, going door-to-door “in the country’s most isolated villages to explain what really happens to girls who leave home with strangers promising good jobs,” patrolling the Nepal-India border, facing their traffickers in court. (In 41 percent of cases of survival or exit from the trade, victims rescue themselves, according to the United Nations.) With token exceptions, Americans in the book are shown in the best light, down to the soap the girls like to watch on TV (“The Bold and the Beautiful”). Maybe it’s a marketing thing to keep readers interested. It’s unnecessary and distorting, because it’s also implicitly absolving of America’s role as a rich, rapacious consumer of the trade.

There is another, and for a journalist less forgivable, use of numbers without context. “Each year, nearly 12,000 Nepali girls are sold by their families,” McCormick writes in the author’s note. The figure is un-sourced. I traced it to a 2001 report by the International Labour Organization’s Program on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC). The number is extrapolated from surveys, interviews and secondary data–not exclusively hard evidence, and the hardest part of it was a survey of only 100 “vulnerable” households, while the extrapolated figure doesn’t distinguish between children trafficked for sex (a majority) and children trafficked for labor (a substantial minority). The same report notes of the 12,000 figure: “Due to the scant information and broad nature of the assumptions, the figure must be read with caution. It is obvious that more research is needed.”

A 2006-07 report by the National Human Rights Commission of Nepal concedes: “There is a lack of scientific data on the numbers of trafficked persons, places of origin and destination, and purposes of trafficking in Nepal.” The report lists numerous studies with figures, all of them speculative, none of them based on verifiable methodology, all of them reflecting “a high degree of discrepancy.”

When victims’ numbers can be documented, they’re inevitably much lower since by nature the trade is underground. The United Nations maintains a portal with the most exhaustive data from around the world, broken down by country, sex, age, including all detected victims of trafficking by year since 2003, plus people convicted or prosecuted, also broken down by country and year. The UN issues an annual “Global Report on Trafficking in persons.” You have to read deep into the report to get at actual numbers, as opposed to percentages and per-100,000 extrapolations. When you do, the report notes that the figures are based on 51,675 victims detected in 166 countries in 2020. Another part of the report gives the figure of 53,800. The State Department issues an annual report on human trafficking. The 2022 report identifies 90,354 victims in 2021 worldwide.

This isn’t to diminish the problem. But stating a likely exaggerated number as fact weakens the case. These unnecessary exaggerations–it isn’t any less of an atrocity if 1,000 girls are trafficked each year from Nepal, so why not just say “thousands” and leave it at that?–are typical of the human-trafficking vocabulary, which has its own exploitation problem: more sensational figures helps fatten law enforcement budgets, media ratings and do-gooders’ fund-raising drives.

None of this lessens the importance of McCormick’s book. It underscores how little we know and how much more there is to know, but also how even in glimpses we know enough to understand that an underworld that includes some of our neighbors is thriving on crimes against children on a planetary scale. If Sold is set in Nepal and India, Lakshmi’s story is in the end tragically borderless.

![]()

For those interested in contributing to the combat against human trafficking, DeliverFund is a founded in 2014 by Nic McKinley, a former CIA agent and a United States Air Force Pararescueman, and Jeremy Mahugh, a former member of the US Special Operations and a Navy SEAL sniper, that uses counterterrorism methodology and tactics to identify human trafficking in illicit ads, then sending actionable intelligence to law enforcement. See the website here.

![]()

The following questions in bold are reproduced here exactly as they appear on the Flagler County school district’s appeals questionnaire for media advisory committees taking up appeals of book challenges–or attempts to ban books–at the district level. Individual committee members are required to fill in their answers before the committee meeting, where the panel members then discuss the book and reach a decision on each appeal. The answers below are provided as an amendment to the preceding review, in the more focused context of the district’s questions, and are of course only the reviewer’s own–in this case, FlaglerLive Editor Pierre Tristam. Committee members may reach vastly different conclusions.

Title: Sold

Author or editor: Patricia McCormick

Publisher: Hyperion/Hachette

Basis of objection: “Materials contain pornography, Materials are not appropriate for the age of student. This book contains explicit aberrant sexual activities including rape of a minor; prostitution; and explicit violence.”

1. What do you feel is the purpose, theme or message of the material?

Sold is an exploration of the psychological degradation of children trafficked for sex, a global problem that thrives on ignorance, lack of awareness and either resources or willingness to combat the trade. It is also an example of how 41 percent of child victims that exit the trade self-rescue, so the problem presented is not hopeless.

2. Is the purpose accomplished? Yes or no answer only.

Yes.

3. This work is most suitable for which grades?

Pre-K: No.

K-5: No.

6-8: Yes.

9-12: Yes.

The protagonist is 13.

4. Are concepts presented in a manner appropriate to the ability and maturity of your suggested audience? Yes or no.

Yes. The style is in the language of a sensitive, observant adolescent. It is accessible and easy to identify with, despite the cultural differences.

5. Does the material stimulate growth in factual knowledge, literary appreciation, aesthetic values, and/or ethical values?

The factual components are very limited, this being fiction. As a literary work, and even though the book is written by journalist–who are notoriously poor writers–Sold shows young readers how the first person singular can be used to powerful effect in spare language rich in symbolism and irony. Aesthetically, there is beauty in the book despite the theme, because of the style. Aesthetics and ethics are two vastly different things, though often one follows from the other. The book is grounded in an ethic of humanism that uses the shocking de-humanization of a child as a call to action.

6. Does the material enable students to make intelligent judgments in their daily lives?

Readers should not be fooled by the setting in India. This is a book with universal application. To the extent that adolescents may as they grow up realize that their parents aren’t infallible, and certainly that strangers are not to be trusted, the book would help students make intelligent judgments, though in different circumstances. There are no known cases of child trafficking in this county, but there are innumerable cases of child abuse, and child sexual abuse, in local families, which narrows the distance between Sold‘s setting in Nepal and Flagler County considerably: children here may not be sold, but Lakshmi’s experience is not that different from those whose fathers or family members are abusing, and who may feel they have no way out, especially when other family members are complicit or in denial. The book could help them to more hopeful means of self-rescue.

7. Does the material offer an opportunity to understand more of the human condition?

Yes. Anyone who still thinks adults, or parents, are inherently virtuous, wise, or have children’s best interest at heart, as opposed to having every capacity of being selfish, cruel, sadistic and just plain inhuman will be disabused a third into this book. There are no child victims without adult crimes. Sold does not flatter the human condition. At the same time, the nobility of Lakshmi does not feel artificial.

8. Does the material offer an opportunity to better understand an appreciate the aspirations, achievements and history of diverse groups of people?

Every child aspires to a good, happy life where parents and adults are loving and nurturing. Lakshmi is no different. She does not stop aspiring to a better life even at the depth of her most hellish moments. The achievements here are personal, the history not a factor, nor is “diversity,” other than the implicit suggestion that when it comes to sexual abuse, both victims and abusers are as diverse as it gets.

CONTENT

1. Is the content timely and/or relevant? Yes or no. Does this work have literary merit? Yes, no, not applicable. The explain.

The content is timely: just last week Flagler Tiger Bay Club devoted its keynote speaker’s slot to human trafficking. I noted the literary merits in the answer to question 5 above.

2. If presented as factual, is the content accurate? Is the factual information in the book current and accurate as far as you are aware? Yes or no, then explain.

The book is presented as fiction, though fiction based on extensive research of a real problem. The protagonist is presented as a composite of actual victims the author interviewed and read about. In that sense, the fiction is factual. There are problems with some of the facts Patricia McCormick states in her author’s note–not inaccuracies so much as lack of context. I detail those issues toward the end of my review above. Those issues in no way discredit the book. They only reflect a common mishandling of human-trafficking data by journalists and others who fear context and understatement might hurt their cause. It won’t, if it’s more accurate.

APPROPRIATENESS

1. Does the material take in consideration the students’ varied interests, abilities and/or maturity levels?

Most adults have no clue about the breadth and gorgon-headed monstrosities of the human trafficking trade. Even Patricia McCormick, the author, did not before she began her book. Students will not come to this because human trafficking is a particular interest, but because they ought to be interested in it from an awareness perspective. And also because victims of child sexual abuse, who are in our midst, will find a lot to relate to in Sold. The book is written for young adults. It is very well calibrated to adolescents’ maturity level.

2. Does the material help to provide representation for various religious, ethnic, and/or cultural groups and the contribution of these groups to American heritage?

That question has not much relevance here, other than to the extent that American heritage’s perverse libido aided by American wealth, entitlement and imperial if not always white supremacy is a huge enabler and contributor to the trafficking and abuse of children in countries where (quiet, ugly) Americans think they’re above the law.

3. Does this material provide representation to students based on race, color, religion, sex, gender, age, marital status, sexual orientation, disability, political or religious beliefs, national or ethnic origin, or genetic information?

It is unfortunate that such an idiotic question is part of a serious questionnaire on literary books that would lose their literary value the moment they would check off all those un-Chekhovian boxes. If they do, then the books more logically belong on the human resources manuals’ section of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s library.

4. Could this work be considered offensive in any way? Note yes or no next to the following categories:

Profanity: No. There is not a single word George Carlin fans would recognize here. Not even the word “sex.”

Brutality: Yes.

Religion or portrayal of religious practices/ideologies: Yes. The stupidity, sexism and lethality of religious practices like the banishment of girls and women to isolated huts during their menstrual cycle is highlighted. But ostracizing women or considering them polluted during their period is not unique to the Nepalese mountains, and is indeed a cherished practice of all major religions, though the Catholic Church holds a special place of honor in the demeaning and hatred of women.

Language: No.

Sexual behavior: Yes.

Manner characters are presented: No.

Violence: Yes.

Prurient behavior: Yes and no. Child abusers behave out of prurient motives, but that behavior, while very much part of the book, is only alluded to and mostly off stage, the way Greek tragedians only killed characters off stage but spoke of it on stage.

Portrayal of any societal groups: Yes.

Cruelty: Yes.

Aberrant behavior: Yes.

Political positions: No, but for the anachronistic white-savior complex that mars parts of the book.

5. Are questionable or offensive elements of this work an important part of the overall development of the story or text?

Yes. The book cannot exist without them. Its point is to reveal the means and costs of aberrant, cruel, prurient behavior, its effects on children. Again: that message should not be lost on victims (and perpetrators) of child abuse, sexual or not, everywhere. They are not a small number in Flagler.

6. Do you feel the material has a purpose for a school library collection? Yes or no.

Yes.

7. Comments specific to the objection:

I would refer that question to my answer in the body of the review in this segment.

8. Additional comments:

Even for an allegedly jaded reader with some awareness of human trafficking, Sold is a brief, powerful, invaluable introduction to the subject. To ban it is to be complicit in its perpetuation.

Recommendation (retain, remove, other), with an explanation of your overall reasoning for the recommendation:

Keep on library shelves, and recommend it as a must-read or anyone who has been to, or risks ending up at, the Family Life Center.

![]()

Bailey’s Mom says

Bravo Pierre! Thank you for presenting this information and summary of the book. It needs to stay on the Library shelf!

Shame on the so-called Moms for (white) Liberty! When will they stop this nonsense!

I urge all people to Choose Humanity and especially Flagler County residents.

Marek says

I agree 100% .

Local says

School is for learning fundamentals. This stuff has no place in the class room. If you think your kid should be reading this stuff…buy them the book! We waste millions on books that will likely never even be taken off the shelves. All the school needs are educational books. We are being left behind by the rest of the world with the “Californiacation” of our once great country.

We also need to remove history books until they fix the outdated history we teach. Columbus didn’t discover America…slavery is taught wrong(Thomas Sowells” The true history of slavery” should be taught.

We need to start over with the basics…STEM is all we need to catch back up with the rest of the world. And throw some updated history in there too.

FlaglerLive says

Sold is not taught in classrooms. It’s available in high school libraries, and only for those who wish to read it. It is not yet available in middle school libraries. Not every parent has the means to buy books, especially for young readers interested in going above and beyond what they’re handed in class.

Pogo says

@Pierre Tristam

The quality of your review is self-evident. The cumulative value of your contribution to your community — inestimable.

@To Whom It May Concern

The usual suspects

https://www.google.com/search?q=who+owns+moms+for+liberty

Special credit where it is due

https://www.google.com/search?q=randy+fine+moms+for+liberty

Good old Randy Fine: From Page, United States House of Representatives, 1990-1991, to BA, Government, Harvard College, 1992-1996, to MBA, General Management, Harvard Business School, 1996-1998, to Managing Director, The Fine Point Group, 2005-present, Member of Board of Directors, Tangam Gaming Incorporated, 2008-present.

https://justfacts.votesmart.org/candidate/biography/172909/randy-fine

Hey Randy, when do you plan on purging the stacks at dear old Harvard? Probably a good thing for you that what happens in Vegas… huh?

Jack Howell says

After my retirement from the Marine Corps, I taught high school JROTC, for 13 years, in four school systems. These schools were in New York City, Waterbury, CT, Rahway, NJ, and Jacksonville, FL. As a result, I got to know not just my JROTC students but many other students.

I think I pretty well know the mindsets of high schoolers. If Moms for Liberty believes they will shield high schoolers from knowing about human sexuality and sexually-orientated books by banning them from school libraries, they are sadly misinformed! First, that responsibility belongs to the individual parent, not you! Second, all one has to do is watch tv movies, the news, the newspaper, or magazines. Sex sells and brings in big money to corporate America! Keep this in mind, the more you raise issues with these books you want to ban, the more the teens will seek them out! So Moms for Liberty, I hate to inform you, but your teen can probably lecture you on human sexuality! They are not as naive as you think. You might win a little squirmish occasionally, but you won’t win the war.

Laurel says

Jack Howell: I wholeheartedly support your comment.

Atwp says

Jack you are right. I don’t remember you saying anything about the internet. Sex sells everywhere including schools. You are right.

Carrie says

Moms for liberty is a cult. They want to co trol your children. They say read the Bible. The Bible is full of sex, hate, killing of children, etc. they want children to live in a fantasy world. However, the real world is everywhere hitting them in the face. If we don’t teach our children protection, and the ways of the world, we are putting them at risk for falling into the traps. Being in abusive relationship. In fact, I find mfl to be abusive & controlling in nature. I wouldn’t let you watch my dog because you are untrustworthy & abusive.