Some 70 people turned up Monday evening for a training session designed to train people interested in serving on the Flagler County school district’s nascent committees that will review attempts by residents to ban books from school library shelves.

a

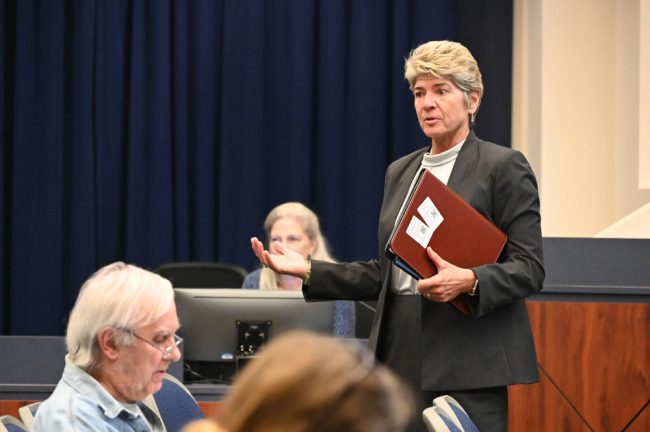

The session was led by Deputy Superintendent Lashakia Moore, with Superintendent Cathy Mittlestadt present throughout, and held at the Government Services Building. There were no histrionics: the audience listened, and when it came time for questions, Moore had ensured that they be written and anonymous. She read the questions and answered them, her humor as assertive and disarming as her command of the issue. She was not challenged.

Members of the public did not have to attend to be considered for appointment. The deadline, however, is Feb. 8. (Here’s the application link.) The selection process will be randomized, by computer, Kristy Gavin, the school board’s attorney, said. It may be completed as soon as Friday. (See all the documents presented and discussed at the meeting here.)

Judging from the questions asked, some of the people in attendance Monday were most startled by the fact that serving on a district committee makes all their work and written interactions on that committee subject to Florida’s Sunshine law, and prevents them from having any interactions about committee business with other committee members, other than during publicly announced committee meetings.

Moore, aside from stressing how important it is for committee members to read the books assigned–people who want books banned typically don’t read the books–cautioned potential participants against attempting to skate by on emotions or opinions alone. The process requires participants to read every book of course, but also to fill out a four-page questionnaire that could get detailed, and bring participants back to their high school or college English classes. “This is going to be a group of us sitting in a room having a conversation around this around a book or around a material,” Moore said, “so it’s important that you come prepared by completing the document and really being ready to defend your position on if it stays or goes.”

Moore summarized the legal language that defines what may be challenged and how, whether the content includes sexual, ideological or religious references or profanity.

“You represent our moral standards as a community,” Moore told the audience. But did they? Moore had also just told the audience that by the district’s most reliable, hard-data measure, only 1 percent of parents have opted to restrict their children from accessing all school library holdings, raising the likelihood that that 1 percent was disproportionately represented in Monday’s audience, among those trending toward bans.

“I think the district has done the best possible with the process,” Carmen Stanford, who publishes Flagler Parent, a school-focused Facebook page with a large following, said. Stanford has signed up to be on a committee. “The book reviews will be thorough, challenging committee members’ thoughts, thus trying to eliminate bias censorship. I personally applaud the district for inviting all parents to participate in the committee.”

Parental involvement on committees is required by law.

The district is working toward establishing up to four such district committees, enabling it to handle several challenges at the same time. By law, each committee must have nine members. By law, those must include six school and faculty members (media specialists, teachers, a principal, district-level staffers), one representative from a parent organization, one representative from the public at large, and one representative from the public library board.

The law is not vague: the district “shall” make those appointments. Nor is it vague about the numbers. There is no room for stacking within each of the required categories.

It is unclear how specifically the 70 people in the audience split between those who favor banning books and those who do not. But based on a scan of familiar faces, neither side appeared to have a clear advantage. That suggests a distinct shift in Flagler County.

Last year the book-banning movement had all the momentum and the attention thanks to shrill theatrics in the wells of school board meeting chambers in Flagler as in other parts of Florida. Freedom-to-read advocates, initially caught by surprise by an entirely new phenomenon (at least in the last century) have since mobilized and now are showing up in equal if not greater force, at least in Flagler.

As Mike Cocchiola put it: “I’m going to participate. I’m compelled to. There has to be a balance.” Cocchiola has frequently spoken to the school board against book bans and other illiberal trends.

“My initial thoughts were positive,” Courtney VandeBunte, a candidate for the school board in the last election, said. She has also signed up. “I like that it’s a randomly selected process. Some thing I’m unsure of, and would like an answer to still, is if there will be a new parent/public representative with each book. I think each time a new book is reviewed, that at least the parent and public representative needs to change. Especially considering the large turnout at yesterday’s meeting, it seems like there’s going to be a large pool of participants to be randomly selected for.”

The three individuals who have so far filed 40 book challenges in Flagler schools between them–Terri McDonald, Cheryl Lackey and Shannon Rambow–at least two of whom were at Monday’s meeting, were asked their reactions to the district’s approach. Rambow and McDonald replied in near-identical emails, saying they were given too little time to respond.

The book-challenge process is similar to the way courts are structured. A case is filed at the trial level. It may be appealed to a district court, then appealed to the supreme court. Similarly, a book challenge must first be filed at the school level (similar to a trial court). That committee’s decision may then be appealed to the district level, whose recommendation goes to the superintendent for a decision. That decision may then be appealed to the school board.

The training was for district-based committees, not school-based committees. School-based committees at Flagler Palm Coast High School and Matanzas High School have been in place and operating since the beginning of the year. (There are no operating committees in middle and elementary schools because no challenges have been filed at those levels.) The school-based committees have rendered a half dozen decisions, including four that have gone in favor of keeping books in their libraries. Those include Sold and Nowhere Girls.

Terri McDonald filed the challenge to Nowhere Girls. Shannon Rambow challenged Sold. Both have appealed the committees’ decisions to keep the books on library shelves. (Both were at Monday’s meeting.)

But the appeals process has limitations. For example, when a school-based committee opts to ban a book, there is no avenue of appeal: no member of the community may challenge that decision. Nor may a member of the public challenge a school library’s decision to “weed” a book, or remove it from circulation even absent a challenge. Librarians routinely weed their collection, generally for reasons unrelated to controversies. But the weeding this year affected several controversial books. Members of the community may ask that a book currently not on library shelves be considered for inclusion.

The book-banning movement is still a new phenomenon: since 2000, book challenges in Flagler County schools could be counted on a single hand, if that, and no books were banned, with such challenges getting addressed by librarians at individual schools. That changed in 2021 as the book-banning movement paired with the “parental rights” movement in Florida turned into an ideological mechanism Gov. Ron DeSantis and Republican lawmakers used as successful campaign strategies to fire up their base.

Florida law controlling challenges changed in key regards to facilitate the assault. Previously, only parents with children in school could challenge library or educational materials at their own child’s school. In other words, only people with standing could do so. Now, any resident of a given district may file a challenge in any school in that district, whether the resident has children in school or not. Book challenges have multiplied since, forcing school and district faculty to divert enormous blocks of time and resources to what until recently had been a non-issue.

The district-level committee system is yet one more level of work and time-intensive involvement. Moore stressed the seriousness of the responsibility. “When you’re reading the book, again, you want to read it in its entirety,” Moore said.

The questions at the end of the meeting touched on the Sunshine law, on whether the district will check participants’ written book reports for plagiarism (it will not), how many review committees there will be (up to four), whether members of a committee may vote by email (no), and so on.

There was, of course, plenty of room for skepticism about a process that resulted from an issue more fabricated from ideological motives than compelled by any serious lack of reliable library standards. Those standards are already provided by professional media specialists, ensuring the appropriateness of what ends up on shelves. The challenge process essentially undermines the specialists’ decisions.

“No matter what the committee recommends, the complainant can keep contesting recommendations to the school board whose moderate members may be fearful of being ousted by DeSantis,” Cocchiola said, a reference to a case in another county where more tolerant school board members were ousted by the governor. “I’m also concerned about vague language in current law. Really, who’s to say what’s pornographic in the context of the total work? And, the term ‘age appropriate’ is exceedingly vague and open to wide interpretation. How do we reach some consensus with extremist activists? Having said all that, I’m giving my best to this.”

Lisa Kopp says

I know much has happened since the 2020 COVID lockdown. Can someone remind me again, what year is this!?!?!

Performative Politics Using Kids says

The most insane thing is the people wanting to ban books had the opportunity to read many of these books as students. They had a choice. They are taking choice away from others because they now feel offended by words on paper.

Brooklyn Library – Free library e-card for all students 13-21 to take out e-books, FREE.

Haymarket Books – Offering FREE e-books on POC.

Read books. Ignore the fascists. They cannot control you or your mind or your ability to think. Never give in.

Tony Mack says

This is a travesty on the First Amendment and an attack by so-called moralists on freedom of thought. Throughout history, only dictators and tyrants have banned and burned books, attacked and vilified teachers while promising “freedom” to the citizens they persecute. Think about that! By the way — these nihilists had better take a look at their Bible — it’s filled with stories of lust, incest, adultery and promiscuity. Seems ripe to be “banned” as well as “Catcher in the Rye”.

Laurel says

Tony Mack: I know of a book written quite a while back, that is currently in most libraries around the country and is considered erotica. I will not, however, mention the book’s title or author as the Mommies of Illiteracy will go after what we adults read, with DeSantis’ blessing. These people are tedious. Big fish in a little bowl.

JimBob says

Interestingly there is an ad for Hillsdale College’s polemic against CRT in the middle of an article on local efforts to ban books.

Deborah Coffey says

Yeah, the Deplorables were shocked that they can’t do their unconstitutional work in secret. Now, everyone can see the kind of anti-Americans they really are. It’ll be on the record!