| Skip introduction and take me straight to today's installment. An introduction to American Impressions: I was the luckiest reporter on the planet. I’d proposed to my editors at the Lakeland Ledger to send me across the country and write an essay on each of the 50 states. They went for it, handing me two credit cards, a camera and the vehicle of my choice--a Chevy Venture I rigged up with a library and a bed.  I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I was not traveling to discover myself or get away from myself, I was not in search of America or of eternal truths. I’m not equipped for that sort of thing, being rather shallow, and I wasn’t going to pretend to understand a state or even a village from a passing week. Nor is this a travelog about food or fun places to visit or quirky people I met along the way. I was just a reporter, picking up stories here and there, choosing for each state one or two themes that struck me as telling about that part of the country, and hoping to build a mosaic of an America every inch a wonder and a puzzle of joys and sorrows to an immigrant hopelessly in love with his adopted country, despite and still. I hope you’ll enjoy the journey. --Pierre Tristam Previous installments:1. Introduction: The Day Before America | 2. Heartland | 3. The Road | 4. Alaska: The New Suburb | 5. Alaska Highway | 6. Montana: Backtracking Lewis and Clark | 7. Montana: Ghost of the Prairie | 8. North Dakota: A Life in Missiles | 9. South Dakota: Crazy |

This wasn’t the way I’d imagined my solo reporting trip across the United States would begin. My database had crashed. My laptop, a 250MB shoebox, wasn’t far behind. I was trying to fix it all with a dialup connection that nagged between 28 and 56K. I was at a Days Inn in a two-motel Missouri nowhere called Kingdom City west of St. Louis. I’d turned on C-Span to drown out the noise of I-70 semis fueling late-century America’s bacchanal, only to hear members of Congress debate releasing on the then-pre-teen Internet the Starr Report on President Clinton’s sexual leaves of crass with Monica Lewinsky.

Three days in, and I had my doubts about pulling off the trip. If it weren’t for a brief encounter with a maid, I might not have continued. By the time I’d spent most of the night and half the next day in calls to a software company in Massachusetts, a hardware company in an undetermined location, my editor in Lakeland, my girlfriend in the house I’d bought just weeks before, the dour Midwestern housekeeper looking an old 25 knocked at my door, which was open, and said as curtly as Pythia, “Your time is up.” I got back on the road.

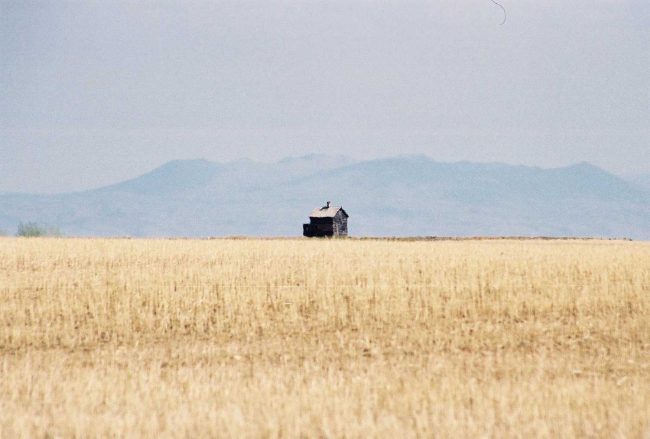

About 20 hours and 450 miles later I woke up to the narcotic drowse of Cedar Bluff State Park in Kansas. I sat there for an hour, stunned by the blue and gold of a landscape somehow parched and flooded, depending on where you looked. Autumn grasses had lost their color. Denuded trees rose from the middle of a lake, actually an artificial reservoir filled in at mid-20th century on what used to be the site of an Indian village that had itself been flooded out a century earlier by the Oregon Trail’s westward-hoing wagons, their ruts still bordering I-70. Every square inch of that seemingly monotonous dead grass was a testament to something unfathomable. I felt the exuberance Kerouac described when he saw “the whole country like an oyster for us to open; and the pearl was there, the pearl was there.” Cedar Bluff was my first in a long rope of pearls.

Few things are to me more romantic than the open road–the American road. It was just about my only romance at the end of my 34th year that late summer of 1998, though I shouldn’t have been so exclusive. I was leaving behind a girlfriend and her child, 15 months into a relationship that would not survive a journey I thought would take six months. It took 15. I returned to an empty house.

None of us could know that when Cheryl and Sadie were watching me finish rigging the Venture. Sadie was 4. She had already been abandoned once by the time I met her mother, by her biological father. The picture I have of them kneeling at a low-lying window in front of the driveway–because in my everlasting reporter’s cruelty, I took a picture–is of Sadie’s incomprehension, and Cheryl’s swollen eyes.

It was September 8. I was leaving the next day. I had 13 days to make 5,500 miles and an 8 p.m. ferry to Kodiak in Homer, Alaska. I’d opted to start there, start big. It was nuts. But it gave me the chance to seize up the continent, get a feel for what I was up against before taking it on state by state. If I could make it up and back in one piece on the Alaska Highway, the rest, I reasoned, would be downhill.

Mentally I’d checked out weeks before. The road is a siren-songed magnet that lures and leers. I couldn’t wait to be strapped to the steering wheel, my ears waxless to hazards. I was as eager for the road as to get away from my newspaper colleagues’ dagger-eyed envy, maybe also from arguments at home that had become more frequent with the enigma of departure approaching.

Night or day my mind would wander over the enormity ahead, and whether it had been such a smart idea to do it alone, though it couldn’t have been any other way. Traveling with others is tourism. Traveling alone is discovery. I reeled between exhilaration and anxiety. Mostly anxiety. Annie Edson Taylor had crisscrossed the United States eight times by the time she strapped herself in a barrel and tumbled over Niagara Falls in 1901. Reading about preparing for the Alaska Highway crossing as if it were an invitation to perdition, I could see some similarities between the two dares.

This was before Facebook, before zoom, before GPS, before Google–born the very week I set off–before iPhones and digital photography made peeping twats of all of us. My phone was a billed-by-the-minute Nokia brick I couldn’t use for dial-up connections. My search engine was AltaVista. My camera was a 35-mm Nikon newsroom reject with two lenses. I would have to develop film along the way, the hunt for 24-hour Fotomats and FedEx stores becoming as critical as finding the next safe place to park my van for the night, since my aversion to motel rooms had me avoiding them wherever possible. On the other hand, it wasn’t 1802 when I’d have to bury my notes and hope that someone would find them to ferry them back east. The difficulties were still luxuries.

My doubt was whether I’d have the words to pull off writing the book-length mosaic I’d promised my editors, to meet what looked like impossible deadlines, to escape mishaps or criminals. I would be unarmed but for a ridiculous wooden baseball bat my brothers and I used to take to the beach in Far Rockaway, Queens, with tennis balls for baseballs.

I had near-zero street-smarts, I spoke with an accent and dove into a country that was splashing back a theft every four seconds that year of unprecedented prosperity, a car theft every 25, a violent crime every 21, a murder every 31 minutes. Also, a traffic crash every five seconds and a traffic injury every 10. Somehow I managed to crisscross the country for 648,000 minutes, 39 million seconds, without a scratch. I’m not boasting. It was luck, nothing else–the kind of luck that spared me snipers’ bullets in Lebanon for no defensible reason, the kind of luck that had me riding the dream of a lifetime with a blank check, though my talent was nowhere near a match for the opportunity: I was Karaoke to Kerouac.

I went 60,000 miles, more than twice the circumference of the planet, without so much as a parking ticket. I don’t think my prudence flatters me. Traveling is about creative recklessness. Mine took idiotic forms, like taking to desert roads alone as if they were highways, or sleeping within eyesight of an ICBM silo, or driving those 60,000 miles with nerdy disregard for basic safety. Always short on time, I’d rigged a shabby desk by the steering wheel so I could take notes or mark up books I was listening to as I sped on. Drive time was for research, setting up interviews, interviewing, repairing the latest erosions with Cheryl or, as I would soon learn, realizing with every phone call to New York that my mother was beginning to lose her memory. It was a journey of discovery as much as of loosening tethers. The manic downs and ups of those 36 hours between Kingdom City and Cedar Bluff were to be the rule, the one thing I had not expected, had not–was not–prepared for.

*

But that mental seesawing between despair and exhilaration was written in the road, like the theme of the entire journey: America as paradox, an America as depressing as it is elating, as ugly as it is sublime, as embracing as it is alien, as admirable as it is distasteful, as diverse as it is conforming, as imaginative and rejuvenating and inspiring as it is petty and rotting and defeating. More than once on the road I found myself tearing up at Johnny Cash’s “Greatest Love Affair,” as saccharine a valentine to America as you’ll hear, as I nauseated in the same moments over the disrobing of the country’s dignities. These jam sessions to American paradox happened everywhere.

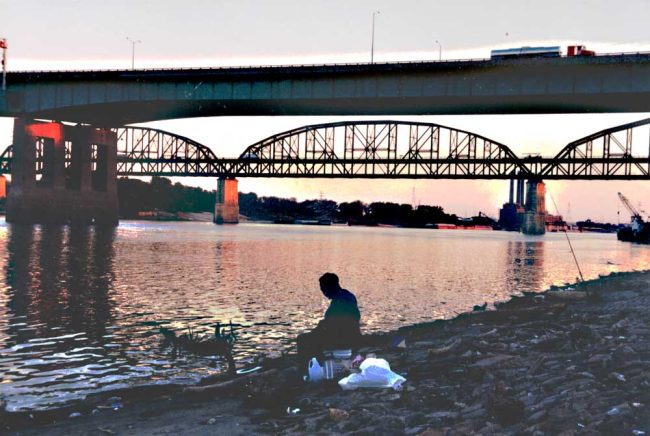

Just south of Manhattan I liberated myself of I-70 for the first time in a thousand miles. I was sick of the traffic, the semis, the RV’s hogging both lanes at turtle speeds, the billboards, the construction, the enticements to gorge on Shoney’s allyoucaneats or to EXIT NOW for a “gentlemen’s club,” as opposed to the more forthright WE BARE ALL of north Florida and South Georgia, where lynching states get right to the point.

Two-lane roads were all serenity. Hardly any cars or combines. The few billboards along the way were of the mom-and-pop variety, made at home from the sort of materials you’d find in the garage, advertising desperate make-ends-meet businesses like Aunt Helen’s antique shop or a family restaurant that offered, as one read in Anglo spray-paint, “really good Mexican food.”

I wanted to stop every other mile to take in Plains looking “like a turbulent ocean suddenly congealed when its waves were at the highest,” as Francis Parkman wrote of a scene that “lay half in light and half in shadow, as the rich sunshine, yellow as gold, was pouring over it.” I hadn’t expected hill and hollow, nor the constant variations of light every time the sun fell a few degrees, nor the sounds ⎯ the sounds, louder than anything I’d been listening to with my windows shut, as if crickets had gathered for a political convention and they’d just nominated their insect by acclamation. The beauty of the landscape was shocking, symphonic. It’s probably there that I had Cash singing his love for America in one ear, newscasters talking semen stains in the other.

By then the sordidness of the Starr report had unfurled its blue dress over the nation. It was written with novelistic flair by Stephen Bates and with vengeful sadism by a 34-year-old rising-star lawyer called Brett Kavanaugh. The two Starr darlings of Gingrich-sneering conservatism had intentionally made the report as salacious as a bare-all lynching. That was the goal, the offenses themselves amounting to nothing more juvenile than furtive hand-and-blow jobs.

I heard parts of the report as I drove between fields of ripe, rust-colored sorghum and golden soybean, read over the radio by doleful newscasters deferring to heartland sensibilities with bales of bleeps. But the Starrlets had written the report for the “heartland,” that dubious invention of value-addled Americans always ready to be titillated by porn cellophaned in sanctimony.

To be effective, to reach the audience it was seeking, the report, like any pair of prosecutors’ closing arguments, had to be worse than the offense. It worked its hex, turning an exceptionally gilded period of late 20th century America into a stage of imperial decadence as imagined by Bob Guccione and Gore Vidal. This, too, was the narcotized America I had woken up to at Cedar Bluff State Park.

*

I had neighbors, a near-elderly couple who pulled their RV behind a pick-up truck and reminded me of Henry Fonda and Katharine Hepburn, just fatter, the sweet scam of high fructose corn syrup distilled from fields all around having ravaged American health for two decades. They sat at their portable table, also in silence. He must have just listened to the news: he was relaxing with a post-coital smoke. She, in anthem to the state’s nickname, threw sunflower seeds at a chipmunk.

I’d looked for a place to pull over half the night on dirt driveways that made me think of The Onion Field, although the country is closer to In Cold Blood. The little town of Holcomb is two hours from here. That was where one night in 1959 paroled convicts Dick Hicock and Perry Edward Smith murdered the four members of the Herb Clutter family in a robbery that didn’t meet their expectations, and where Truman Capote, with Harper Lee’s help, researched the tale, inflamed America’s addiction for true crime and gave Kansas its second Dodge City, when the first had itself been another invention (Dodge City was always more peaceful at its worst than Palm Coast at its best).

There’s a Holcomb Community Park, “Dedicated to the Herb & Bonnie Clutter Family,” there’s a Clutter Memorial Plaque listing the family’s overachievements, and the Clutters’ former 14-room farmhouse still stands, privately owned and briefly given to $5 tours.

But there were 5,580 murders in the United States in 1959, 51 in Kansas. Other than Capote finally pulling off “a kind of controlled extravagance,” as he once told an interviewer two years before the murders, when he was seeking to broaden his skills as a writer of short stories and novels, what made the Clutters special in a country with an unsated appetite for homicidal violence? Nothing, other than a writer’s imagination and a helping of stereotypes that came to be one of the road markers of Kansas the way Aaron Copland–Jewish son of Polish and Lithuanian immigrant storekeepers, grew up in Brooklyn, schooled in Paris–invented the soundtrack of the American West. In that sense, In Cold Blood is just another invention.

At Cedar Bluff State Park, there were no plaques, no memorials, not a word about Carla Baker or Paula Fabrizius. Baker was a college student, biking along a road in nearby Hayes on June 30, 1976, when Francis Nemechek abducted her, stabbed her and hid her body by the reservoir, not far from where I sat romanticizing the scene of chipmunks and golden ponds. Fabrizius was a 16-year-old rangerette working her summer job at the park.

She was on duty on Aug. 21, 1976, when Nemechek abducted, raped, murdered and hid her in a neighboring county. Before that Nemechek had shotgunned two women he’d abducted on I-70 after stopping to help them with a flat tire. They were 19 and 21. They were traveling with a 3-year-old boy. He left the boy to die of cold in an abandoned farmhouse near Hill City–one of the few towns I would coincidentally fall in love with a few months later–where he’d taken all three. As of this writing Nemecheck is in his 70s, serving life in prison in Lansing. There is no equivalent to In Cold Blood for that mass of murders. The most it got was newsprint in local papers and legal opinions.

Onion Field foreboding aside, I knew none of that the night I pulled in at Cedar Bluff. The park’s tourist-luring signage certainly wasn’t going to let on. I learned of it more recently Googling “Cedar Bluff State Park” and “murder,” to test the theory this trip confirmed at every turn: that every square inch of American ground is testament to the unfathomable, a contradiction to assumptions that as often as not can be upended with the sideway glance of a two-second search.

If that principle applies to history, why not to landscapes and culture? Truman Capote framed his epic of the isolated farmhouse murders as a morbid underside of the ordinary heartland. But as that year’s crime tally shows–as any year’s tally shows–there was nothing unordinary about the murders other than the scene-setting.

You can see it in the way The New Yorker subtitled it when it published the story in four parts in 1965: “An unspeakable crime in the heartland.” You can see it in the opening paragraph: “The village of Holcomb stands on the high wheat plains of western Kansas, a lonesome area that other Kansans call ‘out there.’ Some seventy miles east of the Colorado border, the countryside, with its hard blue skies and desert-clear air, has an atmosphere that is rather more Far West than Middle West. The local accent is barbed with a prairie twang, a ranch-hand nasalness, and the men, many of them, wear narrow frontier trousers, Stetsons, and high-heeled boots with pointed toes. The land is flat, and the views are awesomely extensive; horses, herds of cattle, a white cluster of grain elevators rising as gracefully as Greek temples are visible long before a traveller reaches them.”

This is the Jules Verne of the “voyages extraordinaires” writing of the “out there” his readers will never see, the kind of repertorial detail that to its intended urbane audience would have been redundant if it described the Upper East Side or a Jersey suburb, which did not lack for “unspeakable” crimes. The anachronistic reference to Greek temples–like my reference to Pythia in my own second paragraph above–is a pretentious giveaway. Capote is writing as a New Yorker for fellow-New Yorkers. The murder of a family in an isolated farmstead must be assumed to be a shock for the story to work.

Capote couldn’t have made it work had he picked any of the 390 murders in New York City the same year–or even a 16-year-old’s murder of his four family members in Upstate New York 10 months before the Holcomb murders–because Capote’s scene-setting needed the “heartland,” the prairie twangs–the thrill of the word prairie–for contrast, or at least the way editors and publishers in Manhattan imagined the heartland to be: as that wholesome, Christian, moral utopia that members of Congress were fabricating 39 years later for the very same reason as they took the measure of the Starr Report for its shock effect on American sensibilities.

But there is no heartland.

That the murders took place in Kansas didn’t make them exceptional or revealing about Kansas anymore than Holcomb is a more authentic heartland than Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn or Palm Coast’s P Section.

“Contrary to what you may have concluded from television coverage of Oklahoma City,” Russell Baker, the late New York Times columnist, wrote in the aftermath of the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, “violence has always been perfectly at home in the American ‘Heartland.’” The word itself was being “worked half to death since the bombing,” much as The New Yorker had worked it in its subtitle.

By then, and by the time I took to the road, the “heartland” was closer to the way Eric Schlosser would soon describe the meatpacking industry’s impacts in Fast Food Nation: “The changes that have swept through Greeley, Colorado, have also occurred throughout the High Plains, wherever large meatpacking plants operate. Towns like Garden City, Kansas, Grand Island, Nebraska, and Storm Lake, Iowa, now have their own rural ghettos, drugs, poverty, rootlessness, and crime. Some of the most dramatic changes have occurred in Lexington, Nebraska, a small town about three hours west of Omaha. Lexington looks like the sort of place that Norman Rockwell liked to paint: shade trees, picket fences, modest Victorian homes, comfy chairs on front porches. The appearance is deceiving.”

Take away the artistry and scene-setting of In Cold Blood and you’re left with a most ordinary book about a painfully ordinary American phenomenon no one had happened to think of writing about quite that way before, like looking at an actual Campbell’s black bean soup can rather than at a Warhol painting of a black bean soup can. Its plot is one more proof that America is more paradox than exception, often more invention than reality, an invention as old as 1619. This is not a value judgment. Just an observation. The debate over the Starr Report was judgment enough, though about not much more than the degeneracy of the country in the fall of 1998.

And what was I doing if not reinventing my own version of America? At first light I’d made up my own story about Cedar Bluff State Park until I looked through the corrective lens of sideway glances, and even then just barely. The coloring of place with imported assumptions and the mental state of the moment is every traveler’s bane. I would have to be on guard against it in every state, failing more often than not. But the pearls were also there. They were always there. It was time to dive for another.

![]()

marlee says

Your picture entitled Christina’s World reminded me of a poem I wrote

when driving thru the Plains a long time ago….

Wide open sun drenched space

lonely, endless roads, deserted, lifeless farmhouses

windmills standing near

turning with purpose

telling dreams of the past

Michael Cocchiola says

Excellent!

The “Heartland” is still branded as a vision of utopia – the Real America. But we all know it has the same issues as the rest of the country… except for a double dose of MAGAism. That’ll pass with time as do pretty much all fantasies.

Laurel says

Kind of a dark start, eh? I remember reading the “non-fiction novel” years ago. The scary thing for me was these innocent folks kept their doors unlocked as they had no thought of any such thing would happen to anyone in their town. My doors have always been locked. The other scary thing is I sometimes had empathy for Perry Smith, off and on. Hard to admit.

What I remember about Kansas is, around 1973, we stopped at a feed/farm supply store, and I bought a new denim jacket for three dollars! I kept that jacket for a least two decades before I gave it away! Someone, somewhere, is probably wearing it to this day. Made in America!