(© FlaglerLive)

There was an oddly cheery tone to Flagler County’s first-ever non-virtual town hall on suicide prevention Thursday evening, a town hall that drew 150 people and ended on a cheerier note still when participants stuck foamy Rudolph reindeer-like red noses on their sniffers.

“So this was really kind of iffy that we were going to share the red noses, I was a little nervous about it,” Colleen Conklin, the school board member and host of the town hall, said as she explained the scarlet bulbs that had sat weirdly in the center of tables all evening at the Realtors’ building, where the forum took place. “But it actually turned out that today is National Red Nose Day, and not only that, we brought the red noses because we wanted to end on a positive. We wanted to kind of lift the conversation, yes, with red noses.”

And so Conklin, by then in full revivalist mode, asked the people in the audience to put the red noses on, “and remind yourselves to enjoy a good life once in a while. That life, yes, while it’s serious, laughter is good.” She asked them not only to put on the red noses but to look left, look right, “and enjoy a giggle and a laugh, take a selfie, post it online, use the hashtag #flaglercares because we care. You being here tonight proves you care. Totally silly, probably inappropriate, but in the words of Robin Williams, ‘If you’re that depressed, reach out to someone and remember: suicide is a permanent solution to temporary problems.’” (She might have added: Do as Williams said, not as he did.) “But also, no matter what people tell you, words and ideas can change the world. So this is our community, this is our county. Let’s all connect with each other.”

That’s the hope, anyway. Almost two hours earlier, at the beginning of the town hall, Conklin had asked the assembled to text the one word that the gathering evoked most. The words flashed instantly word-cloud-like on a large screen. The more a certain word was texted, the larger it grew on the screen. There were words like “proud,” “sad,” “intrigued,” “inspired” and “grateful,” but by far the largest word was “hopeful.”

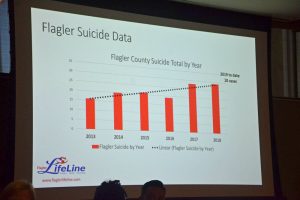

As the evening wore on, the hope most often expressed was to erase Flagler’s distinction as the county with the highest proportion of suicides in 2017, the last year for which numbers were fully available, a distinction that was no surprise to Deanna Oleske, a physician and associate medical examiner in District 23–the district that includes Flagler–who performs autopsies on suicides in the district, among other deaths: more suicide autopsies than car crash autopsies or opioid-overdose autopsies combined, she noted alarmingly. (Five suicides for every overdose, to be specific.) She was one of the five members of the town hall’s panel. She’d been noticing the numbers climb for several years, with no explanation.

Chronic pain. Poor sleep. Depression. Cancer. Dialysis. People dealing with bariatric, or gastric bypass, surgery. Alcohol or other addictions. Those were some of the symptoms–the burdens–people who killed themselves carried to their death. Oleske said there’d been 150 such deaths since 2012 in Flagler alone.

In other words, as many people had taken their own life in Flagler as there were attending the town hall. It was an arresting, unspoken realization, particularly since the audience cut across the same demographics, the same skin tones, the same age groups, but in warm flesh and blood as opposed to the the colder graphics showing the profiles of the dead on the large screen–a mirror of the unimaginable, tabulated.

Conklin earlier had asked audience members to raise their hand if they had been affected by someone close taking his or her own life. Almost every hand went up. “This affects everybody,” Oleske said.

Two years ago Flagler Lifeline emerged. It’s part of the Flagler Cares coalition formed among government and health providers to better coordinate and formulate coherent, county-wide ideas that could address such problems as suicide and, even more urgently, an appalling lack of Flagler-based mental health services: there’s not a single provider, not a single treatment bed, for males, adults or juveniles, in mental health distress in Flagler (there are a few dozen beds for young mothers attempting to overcome addiction), and only one Medicaid provider dispensing medication. Flagler Lifeline, led by Carrie Baird, was behind Thursday’s town hall.

But Flagler Lifeline has no authority, no purse power, no means other than to draw attention to certain issues and coordinate basic outreach for those in need through its relatively new website. One of its surveys, Baird told the audience, showed that almost half of the respondents (49.1 percent) placed mental health issues in Flagler atop their lists of health care concerns, ahead of addiction, homelessness, unemployment and child abuse and neglect.

“And when we asked which health services are most difficult to obtain in Flagler County,,” Baird said, it was “mental health and counseling. Again, over 40 percent of our residents said that this is the hardest health service to access in Flagler County. So you can’t help but see the connection between those two issues for our community.”

Telling as the data was, and as rarely told or understood as it is, it’s the personal stories of suicide that helped keep most of Thursday’s audience in its seats until the end of the forum. One of those stories was that of Palm Coast Mayor Milissa Holland. She’d spoken privately of her mother’s suicide at age 61 in Palm Coast, when Holland was in her second year on the County Commission. She’d never spoken about it so publicly. She told the whole story down to the phone call she knew would come one day but hoped never would, to the walk into her mother’s home with a phalanx of deputies, to her refusal to heed their urging not to go look, though Holland felt she had to, to the sight of her mother’s room entombed in family pictures, and then to how Holland turned in the direction of the bathroom and saw her mother there, on the floor. That’s when she understood the magnitude of the change–for herself and for her children, “because my mom was a tremendous grandmother,” Holland said.

There was a note. “She described the pain she was in in the last moments before she decided to make that ultimate decision,” Holland said. The medical examiner had come on the scene. The clinical commotion that follows those events was filling the house as she herself felt a paralyzing emptiness.

Five years before, Holland’s father Jim Holland, one of the city’s founders and original members of its council, had died of a heart attack. He’d been ill with multiple sclerosis. It was “horrific, very sad and poignant,” Holland said. “But this moment really was undescribable.” She hadn’t felt the same shock to the system, the same feeling of breathlessness, that she did at the sight of her mother, because there hadn’t been so many unanswered questions, the questions so many people who deal with their loved one’s suicide ask themselves for lifetimes. “The questions started rambling in my brain,” she said, “like, what moment led up to this, what must have she felt for those hours going into this, how did she feel in making this decision? All of these moments. And it’s taken me years, literally years, to stand up before each of you today, to really be able to somewhat describe what she must have felt. Because I spent a lifetime dealing with mental illness.”

Holland had grown up with it, with her mother’s mysterious absences of weeks, which she only asked her father about when she became nearly an adult: absences that were actually her mother’s institutionalization time after time as she struggled in silence with bi-polar disorder, and her getting discharged once the insurance ran out, even though she wasn’t “healed,” she wasn’t better, “because I’m not sure she could’ve gotten better.” But mental illness wasn’t recognized as an illness like cancer or diabetes or multiple sclerosis: “the insurance companies would kick her out at the time the insurance would end.” Her mother had attempted suicide several times, had felt shame over it. Family helped, professionals helped.

“Her illness was no different than cancer or diabetes. Her illness, as my father described it, was something different in her brain. It was something that they couldn’t quite get to, the moment of understanding, in making her better,” Holland said. Yet her treatment was always time-limited. “How many people actually are in that position with cancer? None,” Holland said.

Holland’s mother killed herself. Sandra Shank did not, though when she was 18, she did try. She’d been in the military. She suffered from depression. She’d been raped in the military. She ingested an overdose of the very pills she’d been prescribed for her depression, trying to end her life. She failed. Thursday evening, she was one of the panelists, now a 55-year-old woman, still struggling with depression, still coming close to suicide, as she did again a few years ago. But she’s also a teacher, the CEO of Abundant Life Ministries, a group home for abandoned teens. “This is one of the moments for which I survived,” she told the audience, even though “33 years later, there are days when the journey is very difficult.” She illustrated the reality of depression, a lifelong form of mental incarceration that may be managed but rarely defeated.

Michael Crisanto, a mental health therapist and suicide prevention specialist, the fifth panelist, described the life of Don Richie, an Australian resident of Sydney who was to men and women contemplating suicide what Oskar Schindler was to Jews condemned to the gas chambers. Richie lived near a place called the Gap, a set of cliffs over the Tasman Sea favored by people ending their lives. Over 45 years, Richie would walk over to the desperate and strike up a conversation, bring them back to the house for a cup of tea or a beer “to get them away from their mind, away from going over while I’m there,” Richie once told an interviewer. That alone stopped them. He saved 160 or more lives, and was decorated by the Australian government.

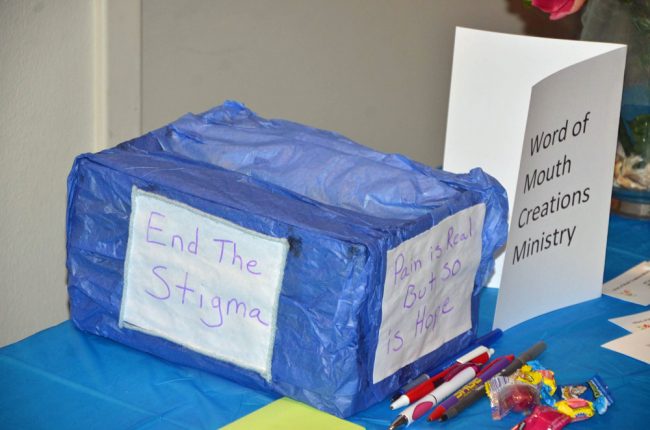

There was no epiphany at the town hall, no breakthrough, no surprise, no direct prescriptions. It was more of an assessment–taking stock of a situation grimmer than it should be, of a health care landscape almost criminally lacking, considering the death toll, and of a call to action, whether it’s Conklin’s urging of more Richie-like interventions in the lives of people struggling with despair or some of the panelists’ call to help reduce the stigma that still imprisons mental health, keeping it from being treated like any other illness. The fact that such a town hall would even take place–that it was so necessary–pointed to the county’s growing awareness and resolve not to remain entirely at the mercy of circumstances.

Flagler Lifeline had left pre-addressed postcards on all the tables. The postcards are addressed to First Lady Casey DeSantis, who’s made mental health a priority. It asks DeSantis to “move the needle” for Flagler, away from its distinction for suicide tallies. But the forum also implicitly underscored the gap between Flagler’s needs, made obvious in surveys, in officials’ advocacy, in those suicide numbers, and the reality of Tallahassee’s indifference: Florida remains the 49th state out of 50 with the lowest per-capita spending on mental health. Yet that’s the context of the stated goal, repeated many times at Thursday’s town hall: to make Flagler’s suicide rate the lowest in the state. If there were no breakthroughs, it nevertheless seemed as if Flagler Lifeline was placing itself between that gap and its victims no less resolutely than Richie at his Gap.

![]()

(© FlaglerLive)

JF says

Maybe you all can educate the Sheriffs Office as well. I had a very close personal friend/boyfriend who was a Flagler Beach Police Officer who was threatening his own life several years ago. It is a shame how the Sheriffs office and their upper staff as well as the Flagler Beach PD. How they treated this man afterwards. I personally know a lot of cops in this county in a good way, but It was disgusting to hear how they talked about this man when he was not even there to defend himself. I can mention on one occasion when I was at Palm Cost Lanes shortly after his incident where I heard several Flagler County Deputies talking about how they wish the “piece of shit should have killed himself” what a disgrace. No wonder this man never sought help. Would you seek help if that’s what they say behind your back. This man had a family and lost everything. Not all, but in let of how the people who are sworn to do a certain job had betrayed him. This mans own boss never even spoke with him after said incident. I would not ask for help either if that’s the standard of treatment here in Flagler County. It is a shame. I just thank god everyday that he is still alive. Why don’t you all open your eyes?!!

John R Brady says

Having worked for 40 years providing emergency mental health services to the citizens of Lehigh County Pennsylvania, I make the following observations.

Typical emergency entry into the mental health system involves local law enforcement officials (LEO). LEO will receive a referral and respond to some crisis and under the laws of most States, LEO will bring a person to a local ER for examination. At this point, the ER doctor has an individual brought in by the police with some description of dangerous behavior towards self or others. That ER doctor has to decide to cut this person loose or commit for further evaluation or treatment. This is usually an easy decision for the ER doctor who has far more to loose in cutting the person loose or punting to a psychiatrist.

And so, a person enters the mental health system at a cost of police resources, ER costs, costs of hospitalization and cost of on-going care. In addition to these financial costs, there is the stigma to the individual and in some cases loss of certain rights e.g. gun ownership.

One solution would be civilian, professional mental health crisis intervention responding to mental health crisis situations. This intervention maybe completed with a LEO assist or in given situations without LEO assist. The goal would be to keep individual out of the ER.

The crisis specialist would perform a mental status exam and determine if there is a need to go to an ER or whether a lesser response is indicated. The response in some cases might be “babysitting” the family or individual through the crisis. Another possible response would be to refer the individual or family to existing community resources or a private counselor or therapist for on-going treatment.

Keeping individuals who should not be in the system, out of the system would result in savings. These savings could be applied to better care for those people who are truly in need of services.

The answer is to have a well published phone number for people making referrals for services for themself or another. This number would be answered 24/7 by crisis specialists who would provide emergency counseling and/or a face to face contact.

Such a crisis team has many benefits and especially to LEO because there would be a significant reduction in calls for service to LEO. LEO could also summon the team to deal with situation that had initially been referred to LEO

All the stake holders need to come together I figure how to pool resources and get something done.

This program was a great start but we must move on.

Resident says

I’m unable to find words to explain how disgusted I am at these people for how they acted about such a serious topic. This is about a brain disease and nothing will help until they bring some psychiatrists to our county, not therapists or screeners but actual doctors to help them.

Dude one says

To little to late for some

Deb Reilly says

Dear Resident, medication alone will not solve this terrible situation. Yes, if there were psychiatrists that accepted Medicaid in Flagler, it would help, but psychotropic meds are not magic and the side effects can make things worse.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2412901/