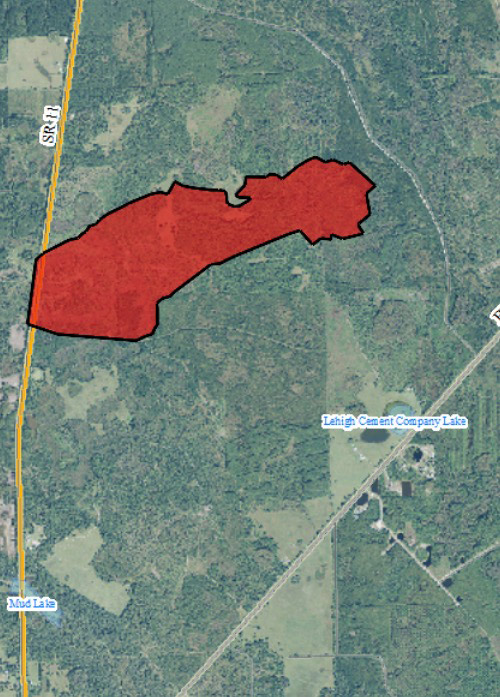

A ride through the 435 acres of last week’s wildfire south of Bunnell reveals the extent—and the limits—of the season’s most serious forest fire yet, and illustrates the concerns of local fire officials in the months ahead as they warn of a more active fire season.

The fire ran rapidly east, aided by winds gusting between 20 and 40 mph, and by already-dry vegetation, thick underbrush, and uninhabited vastness: Not a single house, not a single structure was touched by the fire, and no livestock was hurt, though the land affected is also a grazing area in parts for cattle. In a sense, there are few more remote, uninhabited places where the fire could have burned for such lengthy stretches without affecting human structures.

So fire officials are taking it as a cautionary warning. They’d been sounding that alarm even before the fire.

The long-range forecast from the Florida Forest Service in late January was not hopeful, warning of the combined effects of below-average rainfalls and above-average temperatures possibly for the rest of the year. That means drought conditions are “likely,” Flagler County Fire Chief Don Petito told the County Commission, describing dry lakes and creek beds, and “crunchy”-dry vegetation. He spoke of the forecasters’ “increased chance of severe wildfire conditions. But we hear that every year, so we’re hoping they’re wrong, again.”

They weren’t. Petito was speaking to the County Commission two days before what came to be known as the East Bimini Fire, which broke out last Wednesday on both sides of State Road 11 just south of Bunnell and burned for the next few days, closing SR11 from Cody’s Corner north to Bunnell until Sunday morning. The blaze, Petito said, may well presage a more active wildfire season.

The Bimini fire started almost ridiculously: palmetto blades were rubbing against powerlines along State Road 11. It was a very windy day, with gusts of up to 40 mph, Petito said. He described the cause of the fire as a powerline snapping, hitting the ground and sparking the blaze. The Forest Service’s Julie Allen says the palmetto blades chafed against the powerline enough that they caused a spark, starting the fire (and eventually causing the powerline to snap.) Either way, the fire started at roadside, on the west side of 11, and immediately jumped the road and started burning and running east uncontrollably that night.

The Forest Service was actually fighting a fire further south in the Relay State Wildlife Management Area, southeast of Cody’s Corner, just off the side of the road, with Flagler County Fire Rescue crews. The Fire Service got a call about concerns of another fire further north. When crews checked it out, they realized it was more serious than what was taking place in the Relay area. They very quickly shifted their resources north, and as soon as they started fighting the fire, called for more.

Fears that the fire next time won’t be in as uninhabited an expanse.

The Forest Service is the lead agency in all wildfires, managing the resources assigned to the fire. As soon as crews got to the scene, they requested additional help. The Bunnell Fire Department, Flagler County Fire Rescue and a total of nine Forest Service bulldozers were involved, with the dozers plowing lines around the fire.

Much of the affected land is part of a 657-acre parcel held by the Barton family. The rest of the affected land is owned by Plum Creek Timberlands of Brunswick, Ga. (site of two Georgia Pacific paper mills). On Monday—a day after State Road 11 reopened–cattle grazed obliviously in many parts of the land affected by the fire, which made its way in a relatively narrow but long band from State Road 11 northeast toward Old Haw Creek Road, which it never reached. Large swaths along the way were still green, large swaths were charred, but often not so charred as to have consumed the top of trees.

Will those trees survive? “Some of those will,” Allen Loadholtz, a forest ranger with the Florida Forest Service, said. “What you look for is in the top of them, see where the buds are in the top? As long as the top didn’t completely burn that out, those will probably survive. But if it candles out—they call it candling when it goes completely up the tree, and it goes all the way up the top and it eliminates everything, the needles and the buds at the top—those probably won’t survive.”

“These guys do an incredible job,” said Julie Allen, a wildfire mitigation specialist in the forest service’s Bunnell district, as she drove through the former burn zone. “Structural firefighters, they’ve got bunker gear and breathing apparatus when they go into a fire. Our guys are in that outfit that Allen is in, and they’re in a dozer in the middle of a wildfire, flames all around them, and they’re out there sometimes by themselves.”

They have communication gear, but the only other eyes on them may be the fixed-wing aircraft the Forest Service flies in the district during such emergencies. The plane is housed at the Flagler County Airport.

“Everybody loves the big red firetruck but everybody forgets about that big yellow dozer that’s out there,” Allen said. “Kids see a firetruck, and oh, a fire truck! This happened to us recently. You’ve seen the transports that we transport the dozers out to the fire, correct? Well, they’ve got the emergency lights, and they’re responding to an emergency. And nobody moves out of the way—because they think we’re a tow truck.” But that dozer on a flatbed is an emergency vehicle speeding to get out to that wildfire, where it’s just as critical to plow lines as it would be for a fire engine to defend against a fire moving toward a home.

“The fire itself that burned, the wildfire, was probably a little over 300 acres,” Allen said, “but once we plowed all of those lines around the fire to get ahead of it, we went ahead and did what we call a burn-out. Basically the green that was between the black and those lines that they plowed, we go ahead, to prevent it becoming a hot fire again, we go ahead and burn that out to eliminate the dead fuel.” So by the end it was calculated as a 435-acre fire.

It’s part of living in the Florida paradox: “Florida is a fire-dependent ecosystem, it’s supposed to burn, most people don’t understand that,” Allen says. “That’s why we work so hard to do prescribed burning programs, other mitigation programs where we do mowing and lowing and things of that nature.”

Fires reduce underbrush and enrich the soil, making it healthier for forests to grow. At least when the fires are controlled. The last couple of years the Forest Service has had to cut short its prescribed burning program, which added up to 265,000 acres over two years, because it was overtaken by the fire season both years.

When the Forest Service is not responding to wildfires it’s doing a lot of public education, mowing, plowing lines to reduce the wildfire risks within communities, especially when it comes to the “wildland-urban” interface—where the woods meet the back of homes in subdivisions. The Forest Service is trying very hard to compel developers and residents ensure that there is a minimum of 30 feet of empty space between the back of a house and the woods. “A lot of people don’t comply,” Allen says, because residents like their scenery. “What they don’t understand is that it increases their risk for wildfires.”

It also makes it much more difficult for firefighters to battle a forest fire near a home, because they have a much harder time positioning themselves between a home and a fire. But when they are able to do so, as was the case on two occasions in Palm Coast—in 2011 and in 2016—the results are dramatic: homes are saved even as the flames devour the grounds up to within a few feet of a property.

There’s also a problem with open fire pits, or unmonitored fires, especially on the west side of the county, where fire regulations are less strict than in Palm Coast—and where people may burn yard debris. That produces embers. Unmonitored, it can be dangerous.

And just today (Feb. 21), the Forest Service released its new app, FLBurnTools, to help residents keep well informed, almost in real time, about wildfires (with interactive fire maps), drought and fire dangers, along with prescribed burn information and permits. The app is available in Apple’s App Store and on Google Play.

![]()

Anonymous says

There needs to be more control burning to remove the fuel {under brush} in these pine forests and pine plantations. If control burning or under brush is not removed, then we will see a repeat of the destruction that happened to Palm Coast quite a few years back when the population wasn’t a 1/3 of what it is now and a great number of homes were destroyed. Florida was historically cattle country and the ranchers always control burned to make more pasture and create more grazing for their cattle. By doing this large wild fires were largely prevented. The Timber and pulp wood industries have also impacted our wild fire danger with their crowding of more trees per acre than should be planted. The trees are planted so close together that when a fire gets going on a windy day it can get up in the tops of the trees and there is no way to control it until it runs out of tress to burn. The whole Forrest and everything in it is turned to ash including your house if it happens to be near the trees and there is not enough of a fire prevention setback. A large percentage of Palm Coast is smack dab in the middle of pine forests and pine plantations that were here prior to Palm Coast being developed. With all of the fire equipment Flagler county has purchased over the years it will not stop a wild fire if it gets in the tops of the trees on a very windy dry day. One is pissing into the wind trying to stop it- I’ve been there and done it. These plantations were promoted to get the Agricultural tax rates on the properties and have some income from the property before it is developed into subdivisions.