By Joseph Daniel Ura and Matthew Hall

The Supreme Court’s historically low public standing has prompted a national conversation about the court’s legitimacy. It’s even drawn rare public comment from three sitting Supreme Court justices. What’s referred to by experts as the problem of “judicial legitimacy” may seem abstract, but the court’s faltering public support is about more than popularity.

Eroding legitimacy means that government officials and ordinary people become increasingly unlikely to accept public policies with which they disagree. And Americans need only look to the relatively recent past to understand the stakes of the court’s growing legitimacy problem.

Cost ‘paid in blood’

The Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education shined a light on many white Americans’ tenuous loyalty to the authority of the federal judiciary.

In Brown, the court unanimously held that racial segregation in public education violates the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The justices were abundantly aware that their decision would evoke strong emotions. So Chief Justice Earl Warren worked tirelessly to ensure that the court issued a unanimous, short and readable opinion designed to calm the anticipated popular opposition.

Warren’s efforts were in vain. Rather than recognizing the court’s authoritative interpretation of the Constitution, many white Americans participated in an extended, violent campaign of resistance to the desegregation ruling.

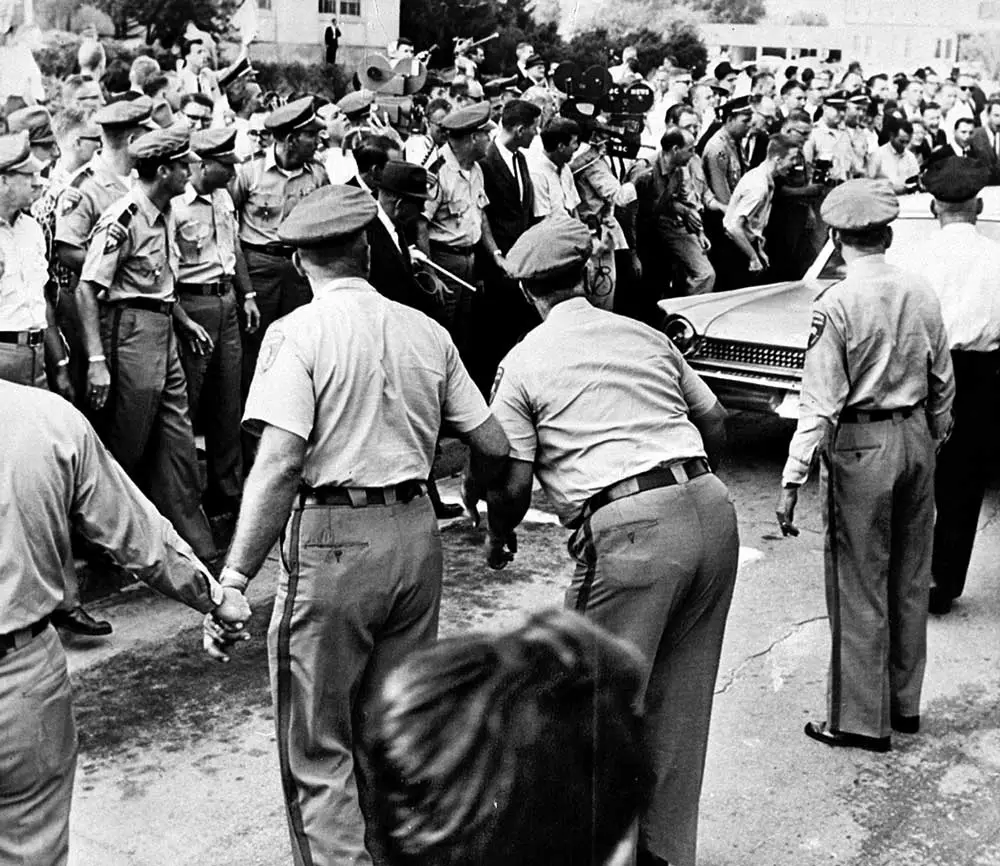

AP photo

The integration of the University of Mississippi in 1962 provides a pointed example of this resistance.

The Supreme Court had backed a lower federal court that ordered the university to admit James Meredith, a Black Air Force veteran. But Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett led a wide-ranging effort to stop Meredith from enrolling at Ole Miss, including deploying state and local police to prevent Meredith from entering campus.

On Sunday, Sept. 30, 1962, Meredith nevertheless arrived on the university’s campus, guarded by dozens of federal marshals, to register and begin classes the next day. A crowd of 2,000 to 3,000 people gathered on campus and broke into a riot. Meredith and the marshals were attacked with Molotov cocktails and gunfire. The marshals fired tear gas in return.

In response, President John F. Kennedy invoked the Insurrection Act of 1807 and ordered the U.S. Army onto campus to restore order and protect Meredith. Overnight, thousands of troops arrived, battling rioters.

Lynn Pelham/Getty Images

The violence finally ended after 15 hours, leaving two civilians dead – both killed by rioters – and dozens of wounded marshals and soldiers in addition to hundreds of injuries among the insurgent mob.

The next day, Oct. 1, Meredith enrolled in the university and attended his first class, but thousands of troops remained in Mississippi for months afterward to preserve order.

What some call “the Battle of Oxford” was fueled by white racism and segregation, but it played out against the backdrop of weak judicial legitimacy. Federal courts did not command enough respect among state officials or ordinary white Mississippians to protect the constitutional rights of Black Mississippians. Neither Gov. Barnett nor the thousands of Oxford rioters were willing to follow the court order for Meredith to enroll at the university.

In the end, the Constitution and the federal courts prevailed only because Kennedy backed them with the Army. But the cost of weak judicial legitimacy was paid in blood.

Legitimacy leads to acceptance

In contrast, when people believe in the legitimacy of their governing institutions, they are more likely to accept, respect and abide by the rules the government – including the courts – ask them to live under, even when the stakes are high and the consequences are far-reaching.

For example, two decades ago, the Supreme Court resolved a disputed presidential election in Bush v. Gore, centered on the counting of ballots in Florida. This time, the court was deeply divided along ideological lines, and its long, complicated and fragmented opinion was based on questionable legal reasoning.

Shay Horse/NurPhoto via Getty Images

But in 2000, the court enjoyed more robust legitimacy among the public than it does today. As a consequence, Florida officials ceased recounting disputed ballots. Vice President Al Gore conceded the election to Texas Gov. George W. Bush, specifically accepting the Supreme Court’s pivotal ruling.

No Democratic senator challenged the validity of Florida’s disputed Electoral College votes for Bush. Congress certified the Electoral College’s vote, and Bush was inaugurated.

Democrats were surely disappointed, and some protested. But the court was viewed as sufficiently legitimate to produce enough acceptance by enough people to ensure a peaceful transition of power. There was no violent riot; there was no open resistance.

Indeed, on the very night that Gore conceded, the chants of his supporters gathered outside tacitly accepted the outcome: “Gore in four!” – as if to say, “We’ll get you next time, because we believe there will be a next time.”

Risks ahead

But what happens when institutions fail to retain citizens’ loyalty?

The Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection showcased the consequences of broken legitimacy. The rioters who stormed the Capitol had lost faith in systems that undergird American democracy: counting presidential votes in the states, tallying Electoral College ballots and settling disputes over election law in the courts.

The rioters may well have believed their country was being stolen, even if such beliefs were baseless. So, they rebelled in the face of a result they didn’t like.

This threat is far from gone. In addition to numerous important questions about individual rights and the scope of government power, the Supreme Court may soon be asked to resolve disputes over the administration of elections and the power to certify election winners – particularly the authority to designate a slate of presidential electors.

Nothing is certain in politics, but the specter of constitutional crisis looms over the United States. It’s dangerously unclear whether the Supreme Court retains enough legitimacy to authoritatively resolve such disputes. If it doesn’t, the court’s abstract legitimacy problem could once again end with blood in the streets.

![]()

Joseph Daniel Ura is Professor of Political Science at Texas A&M University. Matthew Hall is is the David A. Potenziani Memorial College Professor of Constitutional Studies, Professor of Political Science, Concurrent Professor of Law, and Director of the Rooney Center for the Study of American Democracy at the University of Notre Dame.

Foresee says

The political fix is in. First, U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon (very pretty), appointed by Trump, ruled in favor of appointing a Special Master to review the highly classified documents Trump absconded with, a delaying tactic ridiculed by the legal community and which was subsequently overturned by a higher court. Now Chief Justice John Roberts puts a hold on releasing Trump’s tax returns. Trump took the Fifth 440 times in a recent deposition. What is he so desperately hiding? Roberts has disgraced the Supreme Court with his decision and brought its credibility to a new low.

Timothy Patrick Welch says

Remember the process to end slavery in America and fully integrate colored people was opposed by most democrats.

The push then and now to eliminate racism starts with rightlessness and love for our fellow man.

Pierre Tristam says

Remember, the Republicans during Spain’s civil war were armed by Stalin. I doubt anyone would confuse them with Republicans today (in Spain, France or the United States). Your silly analogy, while a favorite of the deflection brigades (considering the rampant racism on the right flank of the American Republican party today), suggests you might need to brush up on your sense of irony.

Bill C says

Too bad that Republican Party from so long ago doesn’t exist anymore except in name only… “colored people”?

Ray W. says

This is not the first of Timothy Patrick Welch’s comments about how democrats of a different era opposed the abolition of slavery and later opposed the integration of southern communities. Are the democrats of those eras the Democrats of today?

Perhaps a snippet from an article in the Atlantic Magazine from earlier this year might help Mr. Welch better understand Mr. Tristam’s characterization of Mr. Welch’s comment as “silly.”

“… But the prayer [Truman] said to himself regularly while in office invoked humility, intellectual honesty, and selflessness. ‘Two persons are sitting at this desk,’ he once told a reporter off the record. ‘One is Harry Truman and the other is the President of the United States, and I have to be sure that Harry Truman remembers on all occasions that the President is there too.’

This commitment to larger values helps explain how a white nationalist like Truman (who didn’t believe in interracial marriage and disapproved of lunch-counter sit-ins) could take the cause of civil rights as seriously as he did. Prompted by the brutal denial of freedom and equality to Black Americans, he pushed for anti-poll-tax and anti-lynching legislation; he signed executive orders calling for the desegregation of the federal workforce and pledging to integrate the military, moves that caused a revolt of Southern Democrats. ‘Here’s telling President Truman,’ the editors of the Jackson Daily News wrote, ‘that the Democratic Party in Mississippi is through with him, now, hereafter and forever.'”

John Dickerson, “The Patron Saint of Lost Presidencies” The Atlantic Magazine, April, 2022

Was President Truman the tipping point of the ultimate and perhaps inevitable migration of the Dixiecrats toward the Republican party, which welcomed them with open arms and still welcomes them to this day? Of course, it can be argued that both embracers influenced each other, moving them both ultimately to what we see today. Was this the beginning of a political realignment that exposes a consistent lack of intellectual rigor in some of Timothy Patrick Welch’s comments, in this case, particularly, the “silly” part?

Aj says

Thank you for this story. Why do the so called white people alwaysit engage in destructive situations. Didn’t want African Americans to enter Ole Miss. Killed Emmitt Till because a white lady lied on him, they beat him so bad until his face was disfigured what a shame. That white liar is still alive. Thank God the killers are dead. They got away with the murder. Look at Arbery Ahmaud, those white men killed him for nothing, a modern day lynching. Thank God they didn’t get away. Twenty years ago it probably would have been a different conclusion. Don’t forget about January 2021. The capital riots because they didn’t use their brains. Most white all crazy for listening to that lying Trump. He said without any proof the election was stolen. Many are serving time because they didn’t think for themselves. Trump is not in prison. They went against the way of the election results and look at the destruction. Thank God they are paying for their unwise decision. The Supreme Court has helped African Americans in many ways. Will they continue to help us time will tell. White people are so destructive they think they are better than other people, I guess because they have done so many destructive things and systematic murders they don’t know anything else. Other people are destructive but the whites are the worse just look at history. The lynching years, the trail of tears, N.C. eugenics program sterilizing people against their will. They tried to breed out Black People, this was in N.C. I can imagine it was nation wide the white man hated us so much. What a shame. Thank God Emmitt Till mother was bold enough to show what the white men did to her child against the will of many people she had an open casket funeral to show the world the atrocity of the white man.

Laurel says

Aj: You comments are blatantly bigoted. This one has little to do with the American confidence of the Supreme Court.

Did all the things you mentioned here happen? Yes they did, but was not backed by all white people. Many white people fought, and some died, during that era trying to help black people get civil rights. I don’t know if this is a surprise to you, but many black slaves were sold to white people by black Africans. Also, there were black people who were slave owners here in the US.

My point is, people are people and can be shitty and/or bigoted, no matter their color. There are plenty of jerks in the world, don’t join in.

Laurel says

How is it that Lindsey Grahame and Donald Trump can go directly to the Supreme Court to get what they want? Trump is a civilian, as we are. Can we do the same? The current Supreme Court is an activist court and the average American civilian has no direct contact. It takes years, and more money than the average American has, to get there, maybe. Now, if the average American civilian does get there, if that civilian does not have political right leaning tendencies, there is no chance of winning.

There is no longer justice.

Ray W. says

Laurel, the issue you refer to is called “original jurisdiction.” There are some issues that go directly to Florida’s Supreme Court or directly to the United States Supreme Court because the respective constitutions provide for original jurisdiction in those courts for those issues. Sen. Graham filed a motion in a federal district court. The vast majority of issues go to the circuit court of appeals. The best example might be Bush v. Gore, which went directly to the U.S. Supreme Court from the Florida Supreme Court in 2000.