In a Florida where union-busting is as rife as the bashing of liberals, Stetson Kennedy is an enduring anachronism. He was born in Jacksonville when Woodrow Wilson was president. He is one of Florida’s leading civil rights and labor activists. In the 1930s and 40s, he was in charge of the Works Progress Administration (WPA)’s folklore, oral history and ethnic studies projects. The he infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups, disrobing their bigotries in The Klan Unmasked (a book formerly titled I Rode With the Ku Klux Klan). Zora Neale Hurston, Woody Guthrie and Erskine Caldwell were among his friends. They’re all dead.

Kennedy is still around.

And at 94, he’s still active in the same causes that have kept him busy for three quarters of a century. On Wednesday, March 30, he will speak at Stetson University at 4 p.m. in the Stetson Room of the Carlton Union Building, 131 E. Minnesota Ave., DeLand.

Click On:

- Dan Warren, Conqueror of St. Augustine at Its Bleakest, Still Heroic After All These Years

- Abigail Lemay, NOW and ACLU Activist at Stetson, Wins National Undergraduate Social Action Award

- Ex-Neo-Nazi White Supremacist Recruiter Lectures on “Turning Away from Hate” At Stetson

- Stetson Kennedy Web Page

- Florida Folklore Society

His talk, “Stetson at Stetson: Legendary Floridian Social Justice Activist in Conversation with Stetson Student Leaders of Social Justice Initiatives,” is free and open to the public. A reception and book-signing will follow.

Three days before his 94th birthday, on Oct. 5, he was in Washington, D.C., one of 200,000 people in the One Nation Working Together rally at the Lincoln Memorial. “It’s been more than three quarters of a century since President Roosevelt succeeded in bringing together organized labor, the NAACP and other civil rights groups to attack the first meltdown,” Kennedy told a reporter from Free Speech Television. “I was there in 1932 and I’m here now. In my opinion, shipping jobs overseas in the face of this current economic meltdown is high treason.”

His verve is undiminished. Almost 60 years ago in Geneva, he was appearing before the United Nations Forced Labor Committee to claim that there were 5.4 million people in the South and Southwest of the United States who were being forced to work on plantations, in turpentine camps and other agricultural occupations by a collaboration between law enforcement, the KKK and business groups.

Kennedy has written extensively on human rights, social issues and folklore. Four of his best-known mid-century works were re-issued in later decades by Florida’s university press system:

- Palmetto Country (Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1942; Florida A&M University Press, 1989), a collection of works of Florida folklore and social history;

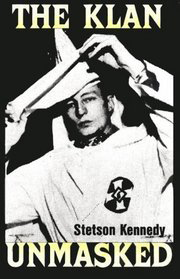

- The Klan Unmasked (Arco Publishers Ltd., 1954; University Press of Florida, 1990), an expose on the Ku Klux Klan and such groups as the Nazi Columbian brownshirts, based on undercover work;

- Jim Crow Guide (Jean-Paul Sartre, Paris, 1955; Lawrence & Wishart, London, 1959; Florida Atlantic University Press, 1990), a satirical “guidebook” for people traveling in the segregated South of the mid 20th century; and

- Southern Exposure (Doubleday, 1946; Florida Atlantic University Press, 1991), a report on social and political conditions in the post-World War II South.

Kennedy is known as much for his folkloric work as for his human rights activism. Palmetto Country, edited by Erskine Caldwell, was the first book in the WPA’s American Folkways Series. Kennedy helped found the Florida Folklore Society and in 1988 won the Florida Folk Heritage Award. In 2005, Kennedy he was inducted into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame.

In 2006, Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner, without diminishing Kennedy’s overall contribution to labor and civil rights, or even his unmasking of the KKK, cast serious doubt on the authenticity of his work methods in a piece for The New York Times Magazine called “Hoodwinked.”

“A close examination of Kennedy’s archives seems to reveal a recurrent theme: legitimate interviews that he conducted with Klan leaders and sympathizers would reappear in The Klan Unmasked in different contexts and with different facts,” they wrote. “In a similar vein, the archives offer evidence that Kennedy covered public Klan events as a reporter but then recast them in his book as undercover exploits. Kennedy had also amassed a great deal of literature about the Klan and other hate groups that he joined, but his own archives suggest that he joined most of these groups by mail. So did Kennedy personally infiltrate the Klan in Atlanta, as portrayed in The Klan Unmasked?”

Kennedy’s antiwar activities also have gained him recognition: In 2001, he earned the “Dr. Benjamin Spock Peacemaker of the Year” award. For additional information about Kennedy, visit www.stetsonkennedy.com

In a 2005 interview with Danny Coeyman, Kennedy said: “I was writing for the Pittsburgh Courier, a Black newspaper, during the marches, and I wrote a column — I signed it ‘Daddy Mention’ – a weekly column and in that column I wrote during the Sixties, during the marches, that ‘Every day gains are being made which can never be taken away.’ And that other Kennedy, the one in the White House, one of his speech writers picked up on it and he said it in one of his speeches too. But then of course we were lying; it’s not true, gains are always in danger of being taken away, it’s the history of the human race: fighting a victory and having it stolen. So we’re trying to do that here and now, like always.”

Leave a Reply