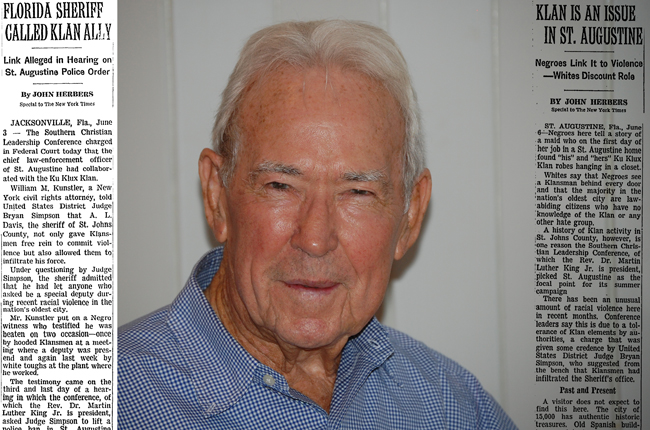

Toward the end of Dan Warren’s talk about his long, violent summer as the 7th Judicial District’s State Attorney in St. Augustine in 1964, when he broke the grip the Ku Klux Klan and the John Birch Society had on the town, a man who could match Warren year for year stood up among the 50 or so people who’d been listening to him and said: “I’d like to express appreciation to you and the work and leadership you gave at that time and I’m sure you’re continuing on with it. And we’re grateful for it.” It was Ray Mercer, for 33 years the postmaster in Bunnell.

“Well,” Warren told Mercer, “I appreciate the sentiment. But believe me sir, it doesn’t take any great feat of courage to do what’s right. It really doesn’t. I mean, you know, I really appreciate your thought, but it really doesn’t take a great feat of courage. I was just taught to do it. Whether I stayed as state attorney didn’t make a bit of difference. I didn’t care, whether I did or not. I knew it was wrong. And I wasn’t going to be a party to it.”

Listen to Dan Warren’s Complete Talk

You could hear it in Warren’s voice—you could sense it, you could see it, as if his 84 years and his blood pressure’s ambushes have done nothing to dull the force that took on St. Augustine’s brood of shield-wielding bigots and won. “I don’t like the sonofabitch,” one of his enemies had said at the time, “but I sure would hate to have him mad at me.”

It was Warren who, appointed State Attorney in 1962, won the position later that year and was reelected two years later, after campaigning in a district that included Flagler County. That year Gov. Farris Bryant appointed him his personal representative in St. Augustine with one mission: end the KKK’s reign of terror in a city where KKK collection jars greeted patrons at the entrance of restaurants and other businesses that considered themselves respectable. He did. The battle culminated in Warren’s decision to desegregate the beaches in conjunction with some of Martin Luther King’s lieutenants.

Hear him tell the story as he did tonight: “My office was in the armory. And one day I’m there and one of the state troopers that had been appointed as a body guard for me—I’d gotten death threats from the Klan—came and said, ‘there’s somebody out in the auditorium that wants to talk to you, and he’s only wearing a bathing suit.’ So I went out there and there was Rev. C.T. Vivian, who was also one of King’s chief aides. And he said, ‘Are you in charge of the law enforcement here?’ And I said yes, I am. He said, ‘Well, I want to go swimming. And I said, well, you’re properly attired, be my guest. He said, ‘Well, you don’t understand, Mr. Warren. Every time we try to go swimming in the public beach, members of the Klan meet us there, and beat us up. They won’t let us go swimming. And I said, Rev. Vivian, will you cooperate with me? He said, ‘It depends on what you mean by cooperation.’ I said will you give me 45 minutes? He said yes. I said give me 45 minutes, you have your organization at the beach, and I’ll guarantee you, you can go swimming.

“And I decided at that moment: now is the time to use the authority that the governor had granted to me when he’d appointed me, back in June. I had my secretary with me, Clara Tillis, and this is the order that I issued to Maj. Jourdan [J.W. Jourdan, deputy inspector of the Florida Highway Patrol]: You are to take sufficient forces under your command, and then you’re to go to the public beaches of St. Augustine and maintain law and order and permit anyone who wants to swim in the public beaches to do so. If anyone interferes with other persons who’d like to swim in the public beaches of St. Augustine, you advise them of disorder, and if they fail and refuse to abide by this order, you are to use such force as is necessary to meet and overcome their resistance. I drove to the beach to see the order was carried out, and when the demonstrators came to the beach, and the Klan jumped out of their pick-up trucks with wooden stakes in their hands and tried to break through law enforcement lines, law enforcement had just about had enough of the Klan and they literally beat the hell out of the members of the Klan and sent three of them to the hospital, and I said, what in the hell have I done? But the message got through, and the next day one of the headlines in the New York newspapers was, ‘Florida Gets Tough with the Klan.’”

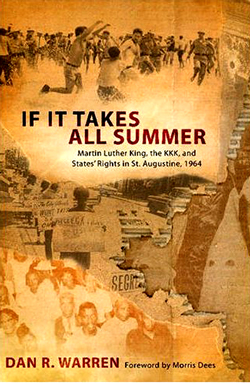

That was just one of the stories this evening, one of many that went into the making of If It Takes All Summer: Martin Luther King, the KKK, and States’ Rights in St. Augustine, 1964, Warren’s 2008 history of that pivotal period of the civil rights era. “Dealing with the Klan was the most important thing I had to do,” Warren said, “and I’m sorry I didn’t crack down sooner than I did, but when I did crack down, I did so with a vengeance.”

The talk and dinner were held at Flagler Beach’s Martin’s Restaurant, upstairs, in a roomful of living history, judging by the audience. The talk was organized by the Flagler County Society and Prunie Rogers, daughter of the late Billy Wadsworth (and sister of Gail Wadsworth, the clerk of court in Flagler). Rogers, whose other sister is a retired judge in Lakeland, had recently heard Warren speak at Lakeland’s Florida Southern College and was so impressed that she urged Rogers to invite him to Flagler. Rogers did. So there he was, taking the evening off.

After 59 years, Warren is still practicing law at his firm, Warren and Warren, where two of his six sons also practice law. Public service couldn’t last long after that hot summer. He resigned in 1968. “I was starving to death,” he said, “I had a large family and the state attorney’s office salary was quite low.”

But Warren still fires off salvos of indignation at the sort of institutional grips that run against his ungrizzled sense of fairness. He’s not so deluded to think that the overt racism he faced down in St. Augustine doesn’t endure in other forms. “It’s more subtle,” he says. “If you go back and look at sentencing in criminal cases, you find a much larger proportion of blacks sentenced to long sentences as opposed to whites.” And differences he calls “draconian” between sentences rendered to young blacks for crack cocaine possession as opposed to far lighter sentences handed whites for powder cocaine, though the two substances have identical effects.

There was an irony to the evening, too. Here was Warren speaking about smashing the backs of segregation to a crowd so uniformly white (there was one black woman in the audience) that, for all its concentration of liberals and progressives, could have been mistaken for a Tea Party event. Merrill Climo, a member of the NAACP, had actually sent out notices about the talk, but somewhat late. “I think there would have been a wonderful response if they knew about it,” he said.

One other missing element: younger faces, to whom the civil rights era might as well be a suburb of Ancient Rome. Warren referred to that gulf in his talk. Half the nation’s population was born after that era. Many among the other half would rather not think about it, downplaying it, or their role in it. History as a bestseller is doing fine. As a conscience, it’s not doing so well, and its heroic figures are few. Warren may claim that it doesn’t take any great feat of courage to do what’s right. But it takes a hero to do it with a force that helps tip the more odious scales of history, as he did.

elaygee says

Dan Warren is a living historical monument who should be treasured

Jim Guines says

I’ll second that emotion!!!!

bill harvey says

we need more like him even today. thank you

Janet Hawkins says

Just curious…… does his two sons that work in his law office share the same point of view as their father