Last Updated: 5:11 p.m.

It’s not just Flagler County: the nation is in the midst of a suicide crisis, youth suicide especially, with 16 people between the ages of 10 and 24 dying of their own hand daily.

Youth suicide declined for almost two decades. But starting in 2007 and over the following 10 years, suicides for among American youths ages 10 to 24 rose 56 percent, according to the Centers for Disease Control. By 2017, suicide in that age group was the second leading cause of death–ahead of homicides, and second only to accidents.

Suicides get little public and media attention because of the perceived stigma–an obstacle to better suicide awareness. Suicide attempts get even less attention, though since 2011 there’s been nearly a 400 percent increase in suicide attempts by self-poisoning alone, among young people.

In Florida, suicide was the eighth-leading cause of death in 2018, but the rate of youth suicide in the 10-to-24 age group, hovering around 6 per 100,000 people until around 2007, has risen above 8 per 100,000 since. Flagler County has had 20 suicides in that age group since 2007, and in 2017, the county had the highest suicide rate in the state.

The reasons for the rising number of suicides are less tractable than the symptoms that accompany the rise: a sharp increase in youth depression–63 percent in the same time span, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Girls are three times as likely as boys to experience depression.

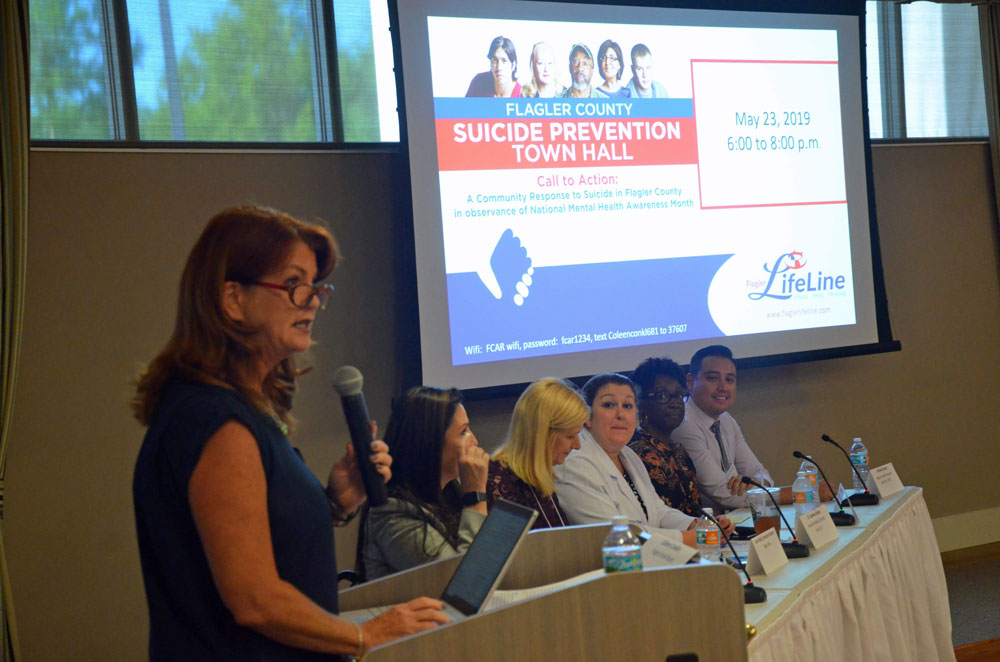

Last May, School Board member Colleen Conklin and Flagler Cares, the coalition of social service organizations that launched a suicide-awareness campaign, organized the county’s first suicide-awareness town hall.

This afternoon, the Flagler County School Board will discuss adopting a proposed suicide-prevention policy, the district’s first, which calls for two hours of continuing education training for all faculty, including administrators. (The policy doesn’t make clear whether the two-hour professional development training would be required annually.)

“This is one of those things that for the last several years has been building, I think Parkland kind of put it over the finish line,” Conklin said, referring to the massacre of 17 people, 14 of them students, at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in South Florida two years ago. The shooting led to a statewide commission and an emphasis on mental health awareness and training in schools. The Flagler district, for example, added counselors and psychologists and incorporated the Sandy Hook Promise program, designed as a conflict-resolution tool, into its training protocols.

“I think it’s critically important for the mental health and wellness of students, for staff and personnel who deal with students to be trained appropriately on how to even handle a student who comes forward and say they’re having suicide ideations,” Conklin said. “How to handle that situation and how to handle it appropriately is critically important.”

School employees are familiar with their obligations under law to report any instance of physical or sexual abuse that they may become aware of. The proposed suicide-prevention policy takes a similar approach, directing “all school district staff members to be alert to a student who exhibits warning signs of self-harm or who threatens or attempts suicide. Any such warning signs or the report of such warning signs from another student or staff

member shall be taken with the utmost seriousness and reported immediately to the Principal or designee.”

The policy is in its earliest stage: the discussion at today’s workshop will be without a vote. The board must first agree, at its next business meeting, to advertise the policy, thus soliciting public input. It may see some revisions, additions or deletions, and only then would be approved as a new policy. But School Board Attorney Kristy Gavin, who was almost insistently resistant to altering the policy, said at today’s workshop that she did not expect substantial changes, this being a model policy that many districts are adopting.

“When we advertise it over the period of time, there are model school policies out there that are more comprehensive,” Conklin said at the workshop. “I hope we’re just not taking the language from the state and just rubber-stamping it and adopting it as a policy instead of looking at what a good, solid model on suicide prevention is.”

“If you look at other states,” Gavin said, “there’s suicide prevention policies that are, like, 80 pages long.”

“I don’t know if we need to go to that extreme, but I would anticipate this policy changing,” Conklin said.

“It may,” Gavin said.

The details will come later: the policy calls for the superintendent to write procedures that would have to be implemented in each school. “The Superintendent will develop an intervention plan for in-school suicide attempts, out of school suicide attempts and an appropriate re-entry process, including a re-entry meeting to discuss the development of a safety plan and additional interventions or supports,” the policy reads.

Principals are to immediately contact guardians or parents of a student exhibiting warning signs, and when the student is being referred to school-based mental health services.

“It all goes back again to training and awareness, looking for signs,” Conklin said, “if you have a student continually falling asleep in class, what else is going on, showing signs of defiance, there may be more to the story. Ensuring teachers are comfortable, or know how to connect with that child or student, is important.”

The heart of the policy is the two-hour training component. The proposal lacks clarity as to the training’s requirement. While the state will designate a school as a “Suicide Prevention Certified School” if all of its eligible faculty complete the training, the proposal does not explicitly make the training a requirement in its current version.

The state Department of Education’s approved list of awareness and prevention programs, some of them online, some of them free, gives an idea of the sort of two-hour sessions the Flagler district could implement: “Youth Suicide: A Silent Epidemic,” “Making Educators Partners in Youth Suicide Prevention,” “More than Sad: Suicide Prevention Education for Teachers and Other School Personnel.” (See the full list here.) Conklin said if costs are attached to any training, those would be borne by the district, not by individual faculty members.

Conklin had a reservation about the proposed policy: while it refers to Baker Acts–the usually involuntary detention of an individual in a mental health facility for up to 72 hours, following a crisis where the individual is threatening harm to self or others–the policy does so only cursorily. But Baker Acts in Flagler schools have been so frequent that the district should have a more defined procedure on how they’re handled.

Conklin asks: Should the district be including in policy how and what happens when a student is Baker Acted and the student returns to school–what safety plans should be in place, what are faculty responsibilities? “My gut reaction is that it should be in policy,” Conklin said, “possibly for parents to understand what happens when students return back, and staff as well.” The school district had 72 Baker Acts involving students in 2018 alone, according to Lynette Shott, the district’s director of student and community engagement.

![]()

What a shame says

I think the program is a great idea. Too bad the School Board didn’t opened their eyes to this dilemma sooner. Once again, reacting to a crisis among our youth, instead of being proactive.