The Ten Books of Christmas: Between Christmas and New Year’s FlaglerLive customarily reduces production. It helps us, and no doubt you, exhausted reader, to take a break from outrage and lurid politics. This year I’m doing something a little different. Instead of only running the usual end-of year sum-ups and fillers, I’m launching the Byblos column and offering the Ten Books of Christmas: every day I’m publishing an original piece of mine on one of the books of the year I found most notable—books old and new, fiction and nonfiction, whether inspired by covid, confinement, covfefe or just the libidinous, inebriating pleasure of reading. No doubt only six or seven readers out there are interested in this sort of thing. That's OK. They’re ignored the rest of the year, so this is for them. I hope they find these, ahem, brief reflections (rather than reviews) at least a little provocative. The days' installments are listed below. --Pierre Tristam |

![]()

There’s an Arabic expression I heard throughout my childhood in Lebanon from my parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles: “may you bury me.” It sounds awfully morbid when I write it out in English, the more so considering the untimely burials I grew up with. But the one-word expression in Arabic (تقبرني, phonetically To’borny) sums up love a-la-Lebanese. The endearment spells out a promise to love to the grave but also the wish–the command, the warning to the gods–that the elder will never have to bury the child, never have to know what Camus called the scandal that is a child’s death. The Lebanese expression’s beauty is its poignancy. It speaks to the trauma of undying love: that it could die before its time.

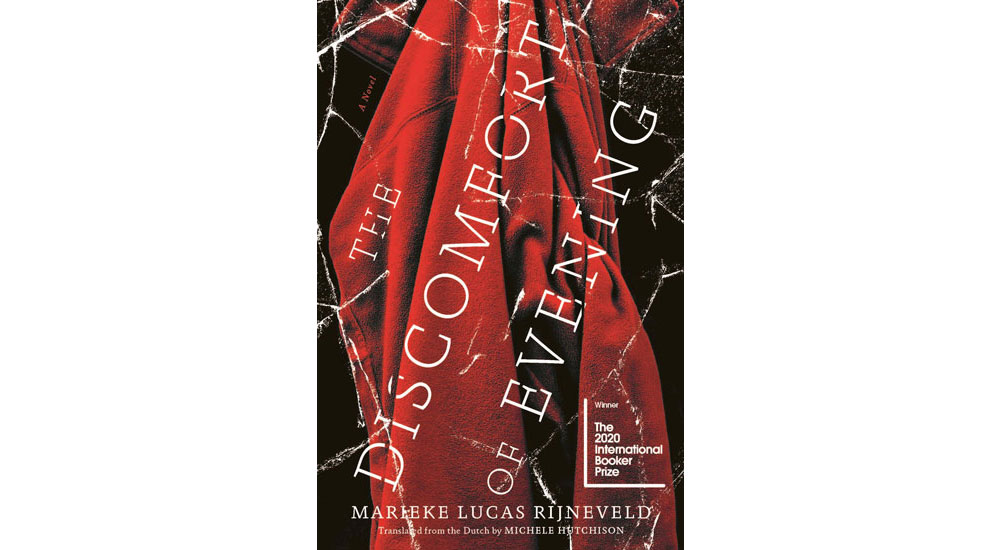

Marieke Lucas Rijneveld’s The Discomfort of Evening is that expression on its head, and not just because the final image of the novel is of the child narrator closing the lid on her own casket, but because by then the 12-year-old girl’s parents have left her with no choice but to conclude that the best way, the only way, to be loved, at least by those two–and who else does she have?–is to die. It might also double up as penance for killing her brother.

Marieke Lucas Rijneveld’s The Discomfort of Evening is that expression on its head, and not just because the final image of the novel is of the child narrator closing the lid on her own casket, but because by then the 12-year-old girl’s parents have left her with no choice but to conclude that the best way, the only way, to be loved, at least by those two–and who else does she have?–is to die. It might also double up as penance for killing her brother.

Rijneveld, who now goes by the pronouns they/them, was born a girl to Reformed parents who took their Calvinism seriously, on a farm in the Netherlands. At age 3 Rijneveld’s 10-year-old brother was struck and killed by a bus. (It cannot be a coincidence that Jas is 10 when the novel begins. Jas is at least in part the imagined continuation of a life unlived.) Rijneveld first wrote about their brother’s loss in a collection of poems that got national attention–it’s not been translated in English yet–then in Discomfort, which last year made them, at 28, the youngest winner of the International Booker Prize. Michele Hutchison shared the prize for her translation from the Dutch of a book she, like many reviewers, called “deeply disturbing.” It is also impossibly beautiful.

The novel begins when Jas is 10, the child of grimly austere farmers in rural Holland. She has two brothers and a sister. Her older brother Matthies goes ice-skating on a lake. Jas is not allowed to go. She is so resentful that she wishes Matthies dead. The ice cracks, he sinks, he dies. Jas blames herself. Matthies’s death glimmers what becomes an inferno of loss as the entirety of the small world Jas had known crumbles and she and her surviving siblings replace it with monstrosities–molestations, animal tortures, “sacrifices,” suicide ideations.

First, blame the parents even as Jas’s fears now include losing them: “I follow them about all day so that they can’t suddenly die and disappear. I always keep them in the corner of my eye, like the tears for Matthies.” She follows them, but they don’t look back. They see past her and her siblings, and what they see is nothing. This book does not make a good case for a “parents’ bill of rights.”

Parents can be toxic enough to their children in the best of times. These parents of Jas’s come pre-equipped with the corsets of half-baked dogmas and rules that substitute for their history. They’re reformed Christians, after all. There is no TV in the house, dial-up Internet only for school, no Googling allowed, adding to the family’s claustrophobia. We learn nothing about the parents except what becomes of them in loss.

But no parent is equipped to handle the death of a child. They had to bury their son. تقبرني didn’t work. The Discomfort of Evening is the decomposition of a family, as revolting and uncomfortable as any proximity to decomposition may be, with luminous moments of humanity. It is written in a style shockingly poetic and lyrical, as if Rijneveld, who wrote the book over six years in their mid-to-late 20s, had tapped into a new language of grief: at once hostile to anything sentimental or endearing and incapable of writing anything trite, untrue or unfamiliar. Don’t expect a linear story, a plot, an intrigue. It is a narrative of impressions: “I’ve learned that the heavens aren’t a wishing-well but a mass grave. Every star is a dead child, and the most beautiful star is Matthies – Mum taught us that.”

Rijneveld says the book started as poems or fragmentary verse. You can see the fragments turning to something like molten glass in front of your eyes as Rijneveld uses them to turn paragraphs and chapters into a mirror of distortions disturbing for being at times too familiar. The feat falters only in the latter third of the novel, when it felt as if the narrative was wearing itself out with repetition and a search for a way out. It’s not a lesser novel for it (even Bellow’s Augie March couldn’t keep it up the entirety of the way through, its exuberance as unsustainable as Discomfort’s agonies). And the revelations don’t cease: “I close my nature book in shock. Ants can carry up to five thousand times their own weight. People are puny in comparison – they can barely lift their own body weight once, let alone the weight of their sorrow.”

But it’s a narrative of gradual vanishing even as Jas begins to lose her girlhood. Jas’s mother “is almost as thin as the manure fork leaning against the wall of the barn.” Jas is so desperate for physical contact with her mother that she stands next to her in the kitchen as she cooks, “ever closer in the hope that she’ll accidentally touch me when she moves the frying pan to the plates set out ready on the counter. Just for a moment. Skin against skin, hunger against hunger.” Jas is the only girl in her section incapable of passing her swimming proficiency exam, no secret why. She develops her first intimations of suicide, spoken out loud to her mother: “‘Maybe I’ll drown,’ I say cautiously, searching my mum’s face in the hope she’ll be startled, that more lines will appear in her skin than when she’s crying for herself, that she’ll stand up and hold me, rock me back and forth like a cumin cheese in a brine bath. My mum doesn’t look up.”

After Matthies dies the parents emptied their water bed in symbolic woe. The water turned to ice, like the couple’s relationship. Mom blames dad for an abortion before they were married. Their son’s death is God’s retribution. They ignore their children, they ignore each other and themselves. On top of it all, Jas’s body is changing, and she becomes aware of others’ bodies, to the point of intrusion, then violation.

The consensus about the disturbing parts of this novel, from my reading of a few reviews and readers’ reactions, seems to center on the physical and sexual traumas Jas describes (as opposed, say, to Jas’s fascination with Hitler, which I found more disturbing), though those are merely the physical symptoms of deeper and more harrowing psychological scars. Jas after her brother’s death refuses to take off a coat that becomes its own repository of decay. She develops pathological constipation that has her father sticking clumps of soap up her bum, his version of an enema. This is a man who looks up Deuteronomy for tips on healthy shitting. Jas is so desperate for her father’s attention–“not being able to poo is the only thing we still talk about, the only thing that makes them look up when I stand in front of them in the kitchen and lift my T-shirt, my swollen belly like an egg with a double yolk”–that she willingly submits to the pain, a suggestion of sadomasochism that elsewhere becomes more than suggestive, “…but according to the pastor, discomfort is good. In discomfort we are real.’”

The parents’ neglect of the three surviving children is the deepest trauma, an uncommitted crime that the children proceed to commit in their place. “They don’t realize that the fewer rules there are, the more we start inventing for ourselves,” Jas says, a nod to William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (also a first novel). Things go sideways. Jas’s brother Obbe–who bangs his head against his headboard every night–drowns a hamster. He uses a sperm-insemination gun to torture Jas’s friend Belle, firing nitrogen in her ass. He “inseminates” his Lego characters, the way he saw it done on the farm. He will force Jas to sacrifice a rooster with a claw hammer.

Jas and her younger sister Hanna–who bites her nails down to bloody cuticles–fantasize about getting rescued off the farm. Hanna dresses up in her father’s suit and she and Jas frenchkiss, playacting the man who comes to take Jas away. Jas suffocates Hanna to make her feel how she feels every night. She puts a noose around her own neck and wonders what it would feel like to sense life “glide out of me, the way I feel a little bit when I’m lying on the sofa butt-naked being a soap dish.” Their sexuality emerges as incomprehensible to them as it is unguided by oblivious parents. (“‘Will we ever grow some?’” Jas’s friend Belle asks, about boobs. “I shake my head. ‘We’ll stay tit-less forever. You only grow them if a boy looks at you for longer than ten minutes.’”) They wouldn’t know what a taboo is. Only to know enough not to tell.

Jas keeps toads and, voodoo-like, imagines that their mating will cause her parents to mate, bringing the family back together, or at least keep her dad from disappearing, making The Discomfort of Evening a romantic love story at heart, deferred and disassociated by a child’s uncomprehending anguish. She speaks to her toads the way Anne Frank in her diary addresses Kitty. It’s her escape from the inescapable, the Holocaust theme only a basement away: the parents forbid the children from going to the basement, where the mother keeps disappearing with bags. Jas imagines Jews are kept there. The mystery of the basement is among the many tensions that lead inevitably to Jas’s end.

But a child’s death isn’t enough. A hedgehog is run-over. Matthies’s death presaged the collapse of the family. The hedgehog’s death presages the collapse of the farm. The cows come down with foot and mouth disease. They have to be exterminated. The child, by then 12, is jaded: “Just like the weather, God can never get it right. If a swan is rescued somewhere in the village, in a different place a parishioner dies.” The parents have become so self-absorbed in their grief, and now their physical demolition, that they’re oblivious to the vet seducing Jas in front of their eyes.

And what of this fixation on Hitler, who keeps appearing in Jas’s thought process like another dare? They share a birthday–April 20–which adds to Jas’s sense of familiarity. “Hitler had lost three brothers and a sister, none of whom made it to the age of six. I’m like him, I thought, and nobody must know it.” Her teacher tells the class Hitler daydreamed and was a germaphobe. She wonders if he sometimes cried when he was alone. She combs her hair the way he did. She crosses off her family members’ names on the calendar where it marks their birthdays, and in place of hers writes his initials, “A.H.” She uses “Heil Hitler” as a password.

You wonder where this is going, and as the vets exterminate the family’s cows, as her brother calls them murderers and Hitlers, Jas fills in the puzzle of her fixation in a child’s mind where hierarchies of horrors naturally don’t exist the way they do in an adult’s mind: “afterwards. I think about the Jewish people who met their fate like hunted-down cattle, about Hitler who was so terrified of illnesses that he started to see people as bacteria, as something you can easily stamp out. The teacher told us during the history lesson that Hitler had fallen through ice when he was four and had been saved by a priest, that some people can fall through ice and it’s better if they’re not rescued. I wondered then why a bad person like Hitler could be saved and not my brother. Why the cows had to die while they hadn’t done anything wrong.”

And always, even through the massacre and the crushing guilt, the longing to love and be loved, to cling to her dad, to see her mom alive and affectionate again–only to actually see her brother Obbe take her to a doctor in town in a wheelbarrow after she collapses and her husband refuses to drive her. Where, you wonder, are child services in all this. (The “elders” do show up by the end, but it may be too late.)

Sometimes the similes, so many of them as fresh-baked as the farming imagery they’re drawn from, sound considerably more grown up than those of a 12 year old would ever imagine (“We find ourselves in loss and we are who we are – vulnerable beings, like stripped starling chicks that fall naked from their nests and hope they’ll be picked up again”). But in the end this is Rijneveld writing, and as accomplished as her children’s voices are, the voice of an important novelist is just as clear, deeply autobiographical though this book is. The author has said their mother alone, out of the entire family, has been willing to read the book. No doubt readers who have no connection to Rijneveld might not get too far in, either. But those who seek to get a sense–not understanding, because who are we kidding? None of us could understand unless we’ve lived it, and heaven forbid any of us should, so just a sense–of the sorrow and grief of desertion on top of death on top of lost faith will be grateful to Rijneveld, and will never forget Jas. May she poop in peace.

![]()

Pierre Tristam is the editor of FlaglerLive. Reach him by email here.

Leave a Reply