If Robert Barry and his attorney Frederick Morello had a bad day Wednesday in their case against Publix, it got worse right from the start today, the third day of trial. Judge Michael Orfinger tossed out one of the two counts against the company without giving the jury a chance to weigh in: the charge that Publix violated the whistleblower act when it fired Barry for dishonesty.

That leaves just one charge for the jury to rule on: whether Barry’s civil, rights were violated. Orfinger is “reserving judgment” on that issue.

Barry, 30, had claimed that he was fired for alerting Publix of a case of sexual harassment against another employee at the Town Center Publix in Palm Coast—Michelle Ashton Brown. But Brown denied having ever been harassed and told Publix as much in a lengthy statement. She claimed Barry and his colleague, Henry Toro, fabricated the harassment charge because they wanted to get rid of their supervisor, Craig Dario, the alleged harasser. They figured that if they stuck a sex harassment accusation on him, he’d get fired.

Publix says it saw through the scheme and fired Barry instead in 2010, ending his six years with the company. Barry sued the following year, claiming he’d been retaliated against. But for a whistleblower act violation to stick at trial, a plaintiff must essentially prove that the company ignored legitimate evidence of wrongdoing, covered it up and retaliated by getting rid of those making accusations.

None of the few witnesses Morello called could show that any of that had taken place. But his dearth of witnesses was only one of the case’s weaknesses. More damaging were his two main witnesses, Barry and Toro, who came off as contradictory and less than exemplary employees. Both had temper issues. Both were caught in lies they acknowledged on the stand, implicitly making Publix’s case that they were dishonest. That was primarily why Publix had fired Barry.

So starting the third day of trial, Publix attorneys moved for a directed verdict by the judge on all counts, which would mean that the judge rather than the jury would issue a verdict (though he’d direct the jury to issue that verdict). “The overwhelming evidence is that Bob Barry made up these sexual harassment accusations to get Craig Dario fired,” Shannon Kelly, one of the two Publix attorneys, said.

Orfinger gave Morello a chance to rebut the argument. Morello mostly referred the judge to his own previous motion for summary judgment, the equivalent of a punt that Kelly seized on to say there was no rebuttal.

“I don’t find that you have proven actual sexual harassment of Ashton Brown, such that if Ashton Brown had presented the evidence you presented here, that she would have been able to prevail,” Orfinger said. “If for no other reason than that there’s been no proof of any alteration in terms of the conditions of her employment, and the incidents that have been testified to with any particularity have been two over the course of approximate three-year area, and while those incidents, if true, can certainly be untoward and something you wouldn’t tolerate in your law office and Mr. Reese and Ms. Kelly wouldn’t tolerate in their office, it’s somewhat different than what the law defines as sexual harassment. So because of a failure to prove actual sexual harassment, I am granting a directed verdict as to the private whistleblower act.”

As it would turn out, even those two alleged acts of perceived vulgar or harassing behavior against Brown, she herself would deny them, as would their alleged perpetrator, Craig Dario.

They were the two main witnesses today. And they—Brown especially—made matters even worse for Barry’s case against Publix.

The jury was not in the courtroom when Orfinger ruled in favor of Publix’s motion. All parties agreed that he would not tell the jury of the directed verdict until the jury is issued its instructions before deliberations. So Morello was left to fight for the civil-rights violation count, where he had to show that Barry was in his right to be concerned about another employee if he perceived that Publix was allowing unlawful employment practices.

In essence, Morello had to show that even if Ashton Brown had not felt that she’d been sexually harassed, harassment had, in fact, taken place, and Barry was right to intervene.

But it was Brown herself who made that part of Morello’s case just as difficult to prove.

And through all of Brown’s testimony, much of the focus was on the import and context of the word butt: “Biscuitbutt” has been a nickname of Brown’s since she was a child—an uncle Christened her with it, she said—and she’s been called “ass-ton,” a play on her middle name, since high school, never er objecting or finding either nicknames offensive.

“At any time in your employment with Publix Have you ever felt sexually harassed?” Kelly asked her.

“No ma’am.”

She learned at one point that Barry had made the various allegations against Dario, she said. “He came to me and told me that he was upset with a lot of ways that Craig was running the store,” Brown said, “and that he wanted, they wanted, him and Henry Toro, wanted to get him fired, get back at him for what he did to them, and that he was going to use sexual harassment as one of those things because that can get him fired, we had zero tolerance for it.”

Barry told her of the plan three or four times. “He just wanted me to go along with what was said, whatever they claimed, the harassment charge was, for me to just agree with it, so that they could get him fired,” she said.

“And what was your response when he approached you?”

“I told him no.”

“You told him no to what?”

‘That I wasn’t going along with it, Craig Dario didn’t harass me. I’d not been harassed.”

“At any point in time did you ever tell Robert Barry that you felt you’d been sexually harassed by Craig Dario?”

“No, I did not.”

“When he came to you and told you to go along with his allegations, do you believe that you’d made it clear to him that you’d never been sexually harassed?”

“Absolutely I do,” Brown said, also noting that she’d never confided in Toro in any way, or told him Dario had ever done anything inappropriate to her.

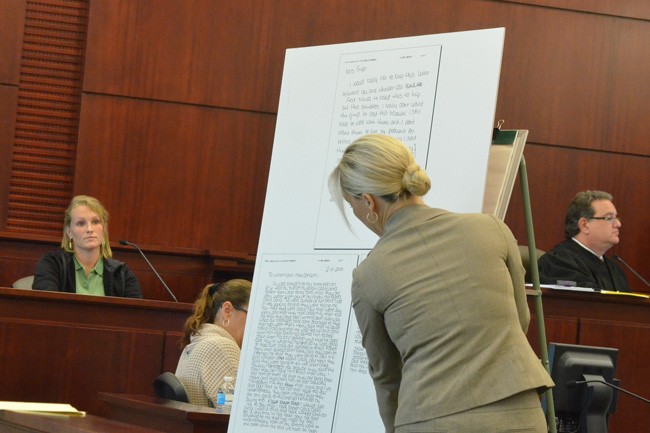

That was just Kelly’s warm-up act for the jury. She then placed on an easel the blown-up three pages of Brown’s cover letter and statement, in her handwriting, disavowing any involvement in the Barry-Torro plan, and had Brown read every word. She’d written it and turned it in to her manager because, she said, she didn’t want Dario fired.

Other than generalities they never specified, Barry and Toro made two specific claims of sexual harassment by Dario against Brown. Kelly took those on in turn.

“Did Craig Dario ever tell you that he wanted to do you doggie style?” Kelly asked.

“No,” Brown said.

“Did Craig Dario ever tell you that he wanted you to give him a blow job?”

“No.”

“Did Craig Dario ever tell you that he wanted a blow job and then put his hand in your mouth and then kissed it saying that he would never wash his hand again?”

“No.”

“If this had happened, what you have done?”

“I would have knocked him out.”

“After knocking him out what would you have done?”

“Called the cops. Told everybody in the store.”

When Morello’s turn came, he was left in the position of trying to prove to Brown that perhaps she had been sexually harassed but didn’t know it. She had none of it. She didn’t think that her nicknames were degrading to women. Morello pressed, looking for an opening as if he were improvising on his feet rather than enacting a strategy, even skirting settled issues by then and at one point elaborating almost obsessively about Brown’s butt appellations, using some she’d never even been called.

“Would you agree that asking somebody for a blow job or doing you doggy style is a pretty—“

“Nasty?”

“Nasty.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Are comments about your ass nasty?”

“Depending, yes. I mean, as far as ass-ton, what I’ve been called all through high school, I don’t find that offensive. If you’re making derogatory remarks about me, yes, that would be pretty nasty.”

“So if a co-employee were to throughout the day to not call you Ashton, and would simply say, look Asston, go over here and do that, Ass-ton, move your Biscuit, hey, Biscuitbutt get over here, hey, Big Butt, it’s time for you to do this, Big Butt, you’re a little late, and if they referred to you as that, that wouldn’t offend you?”

“No, it wouldn’t,” Brown said. “They all did it.”

Morello was out of ammunition.

Dario took the stand in the afternoon. His testimony was not nearly as effective or convincing: he was caught in a few contradictions and went so far as to claim that he’d “never” used vulgar language at work, or even—as the subject was bound to come up by then—called Brown “Asston,” just “Biscuitbutt” (an assertion even Brown had disagreed with). But if Dario’s appearance could have given Morello an opening to make his case, with the alleged harasser in front of him, he did not do so, remaining instead on the periphery of claims that Brown had already discredited.

By day’s end the trial against Publix looked like one of those tropical storms that emerge threateningly out of the Atlantic, give the appearance of churning toward a hurricane, but stumble instead on Caribbean land masses where it degrades and nearly dissipates, leaving behind just a swirl of irritating rain. The trial has entered that rainy phase, which could stretch until Monday: the defense—Publix—said it still had four witnesses, and neither side wants to hand off the deliberations to the jury on Friday afternoon, for fear of a rushed judgment. Absent a twist on Friday (and there’s been a couple so far), the trial may then extend, soggily, to next week.

groot says

Wow, odd. So, is a biscuit butt like a bubble butt?