By Chris Miller

Animals occupy many different roles in our lives. Some consider them members of the family, while others appreciate the reminder to take daily walks.

From service dogs and emotional support animals to the pet waiting to greet us at the front door, animals can bring joy, comfort and companionship to our lives. So naturally, these relationships that form throughout our lives would continue — or at least be commemorated — in death.

The Toronto Star recently reported on efforts to excavate and move over 600 animals from an Oakville, Ont. pet cemetery. As that story highlighted, and as many others will note, burying, embalming or cremating animals is hardly a new practice. These funerary practices offer ways to honour a pet and everything they meant to us.

But what about when the owner dies first? As it turns out, animals are more frequently getting mentioned in the obituaries of their human companions.

How obituaries are changing

Writing an obituary is one of the many practices people conduct when a loved one dies. Formerly, they were reserved for society’s elite, but the democratization of the obituary has resulted in more people being memorialized in this way.

We write obituaries for different purposes. Some of these are purely practical; to announce that someone died, or invite family and friends to the funeral.

More importantly though, obituaries give the bereaved a chance to tell a story about someone they loved. Who were they? What did they enjoy? What were their values?

As one of the studies within the Nonreligion in a Complex Future project, our team has analyzed Canadian obituaries over the last century to understand transformations in how people commemorate the dead. As it turns out, animals are appearing more frequently with each passing year.

As recently as 1990, not a single one of the 53 obituaries published on a given Saturday in the Toronto Star mentioned any pets. This steadily started to change, however. We learn that, in 1991, Harriet will be “sadly missed by all of her friends and animals.” Likewise, Berton — who died in 1998 — was “sadly missed by his ‘good boy Scamp.’”

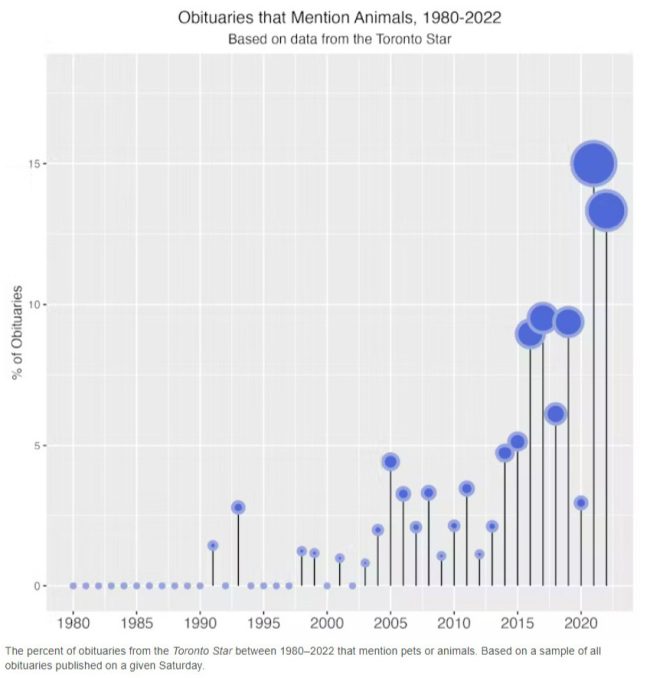

By the mid-2000s, roughly one to four per cent of obituaries mentioned pets. Since 2015, this number has climbed as high as 15 per cent.

Granted, these figures are not exactly overwhelming. In a sample from 1980 to 2022 containing 3,241 obituaries, only 79 mention animals. However, this minor uptick points to a transformation in how people compose obituaries.

Telling personal stories

Our research shows that, since the early 1900s, obituaries have grown progressively longer. The old standard was short notices stating the deceased’s name, age and where they died — all in the space of about four lines. In recent years, the mean length has grown to around 40 lines, with some reaching over 100 lines.

This added space leaves room for more information about the deceased. For example, over 80 per cent of recent obituaries mention the deceased’s children. This is up from about 50 per cent prior to 1960.

Recent obituaries are also more likely to mention the deceased’s education, occupation or hobbies. Beyond just listing attributes, it is common to see rich, detailed descriptions. Rather than be defined by their job title, we read that one man was “a dedicated visionary who remained proud of and loyal to his many employees and colleagues.”

Our furry friends

As obituaries grow longer and more detailed, it only seems fair that animals get some attention. It has become more common to mention someone’s pet, or love of animals. Passages also grow more detailed. Beyond the pet’s name, we learn whether they were a “hoity-toity poodle,” a “loyal companion” or “the best dog ever.”

Occupation is another staple of obituaries. For Mary, who died in 2019, a career highlight while working at Nestle Purina was “inducting various heroic pets and service dogs into the Purina Hall of Fame.” Not just a professional passion; Mary also had six black Labradors at home.

Hobbies and interests are becoming more common in death notices. For Bobby, these included “sitting in his garden with his dog, Chloe” and “being entertained by his beloved parrot, Pookie.”

Rather than send the family flowers, many obituaries now close by requesting donations in the deceased’s memory. Unsurprisingly, groups like the Humane Society, the Farley Foundation and various nature conservancy groups are growing in popularity.

The new ways we grieve

This trend in death notices hints at a broader societal shift. Namely, people are placing greater value on nature and non-human animals. The reasons behind this turn are varied and complex. But the evidence — in obituaries and beyond — suggests people are finding meaningful connection through the natural world and with other-than-human creatures.

Animals aside, obituaries also reveal important transformations in how we commemorate the dead. These were once brief, formulaic texts (and some still are). But more frequently, obituaries are windows into the life of a person. They can be sad or tragic, but also funny, sarcastic and heartwarming.

Above all, obituaries are now more personal. To commemorate the lasting memory of someone they loved, families want to share with the world what made that person special. This can be told through the activities, people or pets that brought them joy throughout their lives. For some, this means cheering for their favourite hockey team, or recalling the time they scored a hole-in-one, and, often, the furry friend they curled up with at the end of a long day.

![]()

Chris Miller is a Postdoctoral fellow in the Nonreligion in a Complex Future project at L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa.

Marek says

They deserve it.