By Barbara Clark Smith

When modern Americans call themselves patriots, they are evoking a sentiment that is 250 years old.

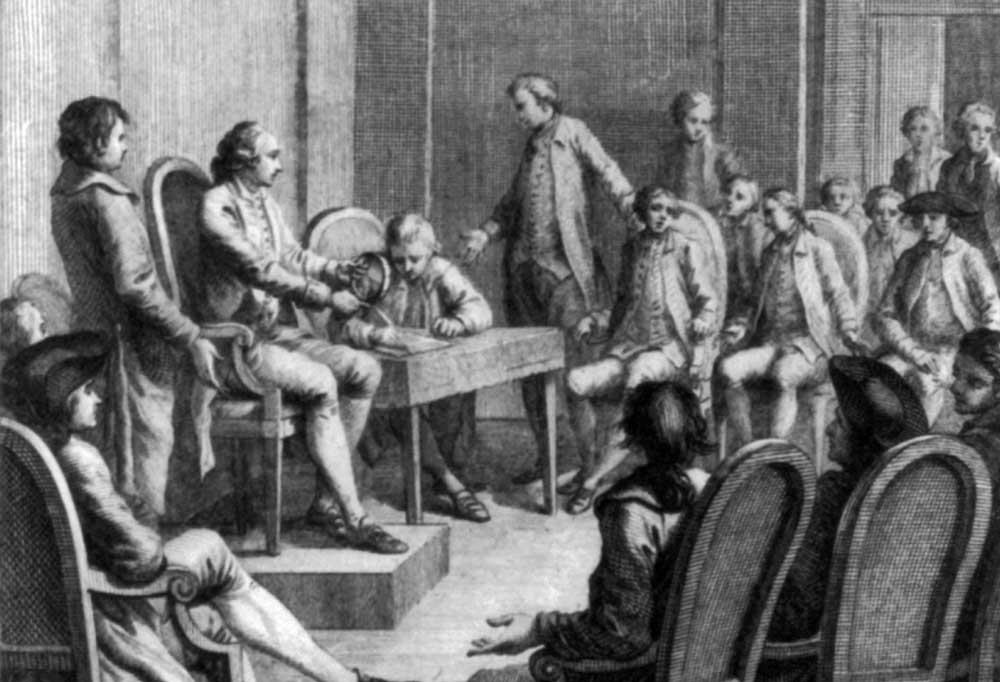

In September 1774, nearly two years before the Declaration of Independence, delegates from 12 of the 13 Colonies gathered in the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. They quickly hammered out a political, economic and cultural program to unify the so-called “Patriot” movement against British rule.

As a Smithsonian curator who studies American identity, I explore the often forgotten ways that the First Continental Congress mobilized an unprecedented number of Colonists behind shared commitments. Most important, perhaps, they established critical terms by which contemporaries measured patriotism – and identified nonpatriots – through the early years of revolution.

The delegates met to address an immediate crisis. Great Britain’s Parliament had recently imposed a series of measures explicitly meant to punish the Colonies for the Boston Tea Party’s destruction of tea in Boston Harbor.

The so-called Intolerable Acts forcibly closed the port of Boston, radically curtailed the representative branches of the Massachusetts government and provided for quartering of troops in any of the Colonies without consent from their legislatures.

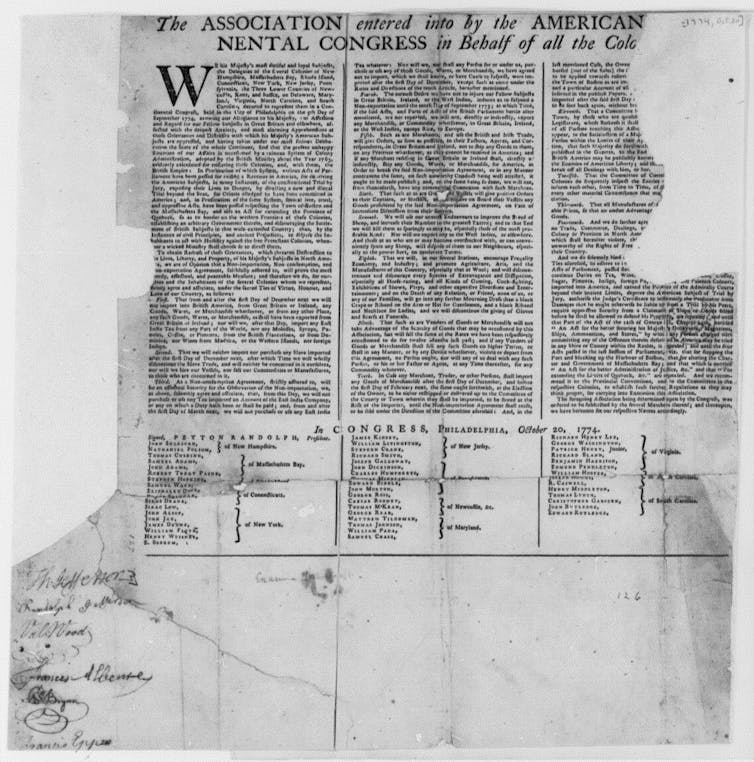

Taken together, these measures “threaten Destruction to the Lives, Liberty, and Property, of his Majesty’s Subjects in North America,” wrote the delegates to the Congress. They rapidly proposed “the most speedy, effectual, and peaceable Measure” they could imagine to counter the British punishments – a “Non-importation, Non-consumption, and Non-exportation Agreement,” called the “Continental Association.”

They built the association on earlier efforts to limit trade with Britain, adopted by various Colonies or seaport towns. Now the Congress went further, promulgating a sweeping trade boycott for all 13 Colonies to join at once and urging every supporter of Colonial rights from New Hampshire to Georgia to accept its restrictions.

Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons

New economic connections

The Continental Association called for American merchants to end all importation of British manufactured goods and for American consumers to refuse to purchase such items, starting on Dec. 1, 1774.

There would be no more fine silks, Irish linens or Indian cottons; no fashionable accoutrements, such as decorative ribbons and lace, parasols or fans. Americans would not purchase European paints, hardware or furnishings; no West Indies molasses or coffee; nor, of course, East India tea. Importing such goods had left the Colonies in debt.

The agreement also banned occasions associated with luxury consumption, such as theatergoing, assemblies and balls, horse races and other expensive entertainments. It even changed funeral rituals by banning imported mourning clothes and the costly silk gloves that the bereaved commonly presented to mourners at these ceremonies.

Equally important, the Continental Association encouraged household production within the Colonies to supplant goods previously bought from Britain. It discouraged consumption of lamb, as a measure to increase stocks of wool for Colonial cloth-making. It relied on urban mechanics and farm households – women as well as men – to increase their manufacturing to replace other English goods now forbidden.

The idea was to create new networks of trade within the Colonies, replacing Colonists’ dependence on Britain with mutual interdependence. Prosperous consumers would now patronize their producing neighbors – putting money into those neighbors’ pockets – by purchasing homespun cloth, herbal teas and other items that were American-made. Finally, the Continental Association forbade dealers from raising prices on English goods as they became scarce.

The Continental Association made the terms of so-called “Patriot” behavior clear: A supporter of American rights would give up British imports, promote American-made goods and forgo undue profits in business.

Those who violated the terms of the pact would be labeled “foes to the rights of British America.”

National Museum of American History

Mobilization

Even as the Congress adjourned, supporters of the proposed program took action. Voters in towns, counties and seaports began electing committees to enforce the Continental Association.

To ensure community solidarity, some localities chose political nobodies to serve alongside established leaders. Ordinary men and even women who, as widows, were sometimes heads of households began signing on to written copies of the agreement.

From Dec. 1, 1774, the new rules of trade created a public panorama of economic and political actions in marketplaces, on seaport wharves and in meetings held in courthouses, meeting houses and taverns. Committeemen inspected merchant warehouses for banned goods and questioned suspected violators of the pact. They published the names of the unrepentant in the public newspapers – often labeled as a sign for “friends of their country” to end all dealings with those violators, now identified as “enemies” to American liberty.

Over the following months, newspapers printed reports of committee decisions, as well as rumors, accusations, apologies and accounts of crowds that confronted recalcitrant dealers or unreformed drinkers of tea.

Colonial readers learned such things as these: A public meeting in Gloucester County, Pennsylvania, called for enforcing the association as if it were “enacted into law.” A merchant named John Armstrong in Isle of Wight, Virginia, regretted violating the association and now promised to reform. Blacksmiths in Worcester, Massachusetts, pledged not to perform work for non-associators. Women in Hartford, Connecticut, gathered to spin thread for weavers to turn into cloth for the poor. A tea dealer in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, apologized for hawking tea and even publicly burned his tea supply. An alderman of Philadelphia had been buried in the plainest of funerals – conducted in strict accord with requirements of the Continental Association.

Since editors routinely reprinted news from other papers, readers could observe their fellow patriots at work even in Colonies far away. Readers in, say, the Carolinas could feel a solidarity with like-minded Colonists in New Hampshire or New York.

‘One people’

The cumulative effect of this broad public mobilization appears, I believe, in the very first sentence of the Declaration of Independence. In July 1776, the Second Continental Congress described inhabitants of the 13 Colonies as “one people,” fully capable of asserting independence from “another” people – those Britons across the Atlantic.

In my view, the experience of the Continental Association of 1774 played a critical role in forming the 13 Colonies into such a “one.” Surely, it helped to convince Americans of different regions, interests, backgrounds and beliefs that they could act as patriots, by pursuing a common interest beyond their differences. They had already associated together, as the First Continental Congress phrased it, “under the Ties of Virtue, Honour, and Love of our Country.” Perhaps there is something there worth commemorating today.

![]()

Barbara Clark Smith is Curator at the Division of Political History at the Smithsonian Institution.

Leave a Reply