Last February 11, Avery (*), a sixth grader, waited until the end of class to approach her teacher at her middle school in Palm Coast.

“She sat in the student seat next to me, and she said, can I talk to you?” her teacher recalled. “And I said, Sure. And she said, It’s about my family.” The bell rang. Teacher and student paused as the students filed out. When the room was empty, Avery said, without a single prompt from her teacher: “My stepfather raped me, and he did a few days ago as well.”

The teacher’s protective protocols kicked in. Moments later Avery was in a school conference room with her teacher, a health counselor and a sheriff’s deputy.

“She was very open and sharing a lot of things,” the teacher said. “So even without questioning, she was sharing a lot.”

It happened in her parents’ bedroom when her mother was at work. Her mother worked nights. Avery “would go in there to, I guess cuddle, is kind of how it sounded like it started,” the teacher said. “This has happened since age nine, and it sounds like a lot of times she would consent to cuddle, but then it would turn into more of him wanting to–him taking his pants off, him wanting to go further with it by having sex or oral sex. He also said that he would make her a sandwich if he gave her a blow job. Just a lot of inappropriate things were coming out.”

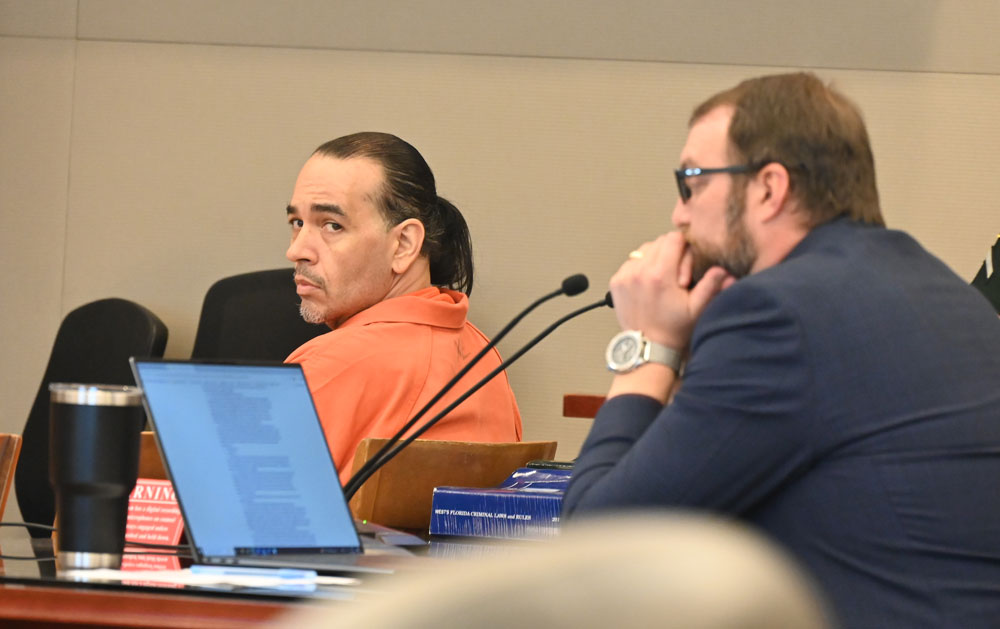

Him was Kristopher Henriqson, a 47-year-old former resident of Lindsay Drive in Palm Coast and a federal felon twice over who served prison time for fraud, and again for selling pot.

Henriqson has been held without bond at the Flagler County jail since his arrest on Feb. 11, not long after Avery’s disclosures in the school conference room. He faces 11 charges, including two capital felony charges that would make him eligible for the death penalty under Florida’s two-year-old law restoring that penalty (but not under federal law), a life felony and seven first-degree felonies, each with a maximum penalty of 30 years in prison.

Henriqson has so far turned down an offer of 40 or 45 years in prison, likely because it would equate to a life term anyway as he’d have to serve the time day for day, with no eligibility for early release. He has done so even though this case is not relying only on hearsay or circumstantial evidence, but on his own admissions in a phone call when he didn’t know he was being recorded, and on DNA from his sperm on the girl’s chest.

He was in court this afternoon for a hearing before Circuit Judge Dawn Nichols on several motions Assistant State Attorney Melissa Clark filed ahead of his trial later this year, among them a motion to let what would otherwise be considered hearsay be admitted as evidence.

“So to make sure I understand, did Avery disclose to you then specifically oral sex and vaginal sex?” Clark asked the teacher, who was zooming in from work.

“Yeah, she mentioned both of them,” the teacher said.

“Did she talk at all about why she hadn’t disclosed this sooner?”

“She said that her stepfather said that they would both get in trouble, so not to say anything,” the teacher said.

The hearsay in this case was the account by the middle school teacher, a similar account by the health counselor at the same school, and the video-recorded interview Rob Baca of the University of Florida First Coast Child Protection Team conducted with Avery, in which she was most detailed about the alleged rapes and other assaults. Avery said Henriqson would offer her $10 to $20 to assault her, reward her with access to a computer tablet and expose her to pornography. The assaults stretched over three years.

All three adults testified today, two of them by zoom, all of them to an empty gallery. Avery, the health counselor testified, said she told her that “she had been raped by him in the past, that there was ongoing sexual abuse for many years, and she was finally ready to tell someone,” the counselor testified. The assaults started when she was 9.

Such hearsay is almost always admitted as evidence in this sort of trial, as it was today by the judge. (Clark might have also had friends of Avery testify, but she told the court she will not, relying instead on the adults. Clark is loath to have any child testify, victims especially, and leaves those necessities as last resorts.)

The only question was whether the entirety of the video interview should be played to the jury or not. Clark intends to redact portions of the interview where Avery talks about her brother, now 11, and his inappropriate behavior, which led to punishments, including corporal punishment. Avery said he abused her physically but not sexually. Clark doesn’t consider that information relevant to the case. “I just don’t want to muddy the waters and confuse the jurors,” Clark said.

Assistant Public Defender Spencer O’Neal had no objections to the teacher, the health counselor and the forensic interviewers testifying, as they will at trial, and introducing hearsay. He objects to the video being redacted. He does think the issue with her brother is relevant, and today revealed what may be his strategy at trial.

“She’s not only angry at Mr. Henriqson, but she’s angry at everyone. She’s angry at her family,” O’Neal told the judge. “So much so that when she comes out with these allegations, she doesn’t only make allegations against him, but she keeps telling people at the CPT video and at the school about allegations against her brother, which, honestly, when I hear them, they sound like relatively normal things that a little kid would do. She makes allegations against her family, as far as you know, corporal punishment, how that may be abusive, and she’s essentially throwing the kitchen sink at the whole family. It goes to, as far as our argument, that her disclosures all come out at once. It’s all meant to be against everyone.”

The implication is that between the anger, the immaturity and the lumping of sexual allegations against Henriqson among petty allegations against her family might shed light about “her frame of mind and what she was thinking and what she was doing,” in the defense attorney’s words, and presumably bring doubt to the truthfulness of the gravity of those allegations.

“So that’s the nature of the argument. That’s really what we’re trying to get into,” O’Neal argued. “We’re asking for the whole thing to be played. I do believe it’s relevant.”

The judge was skeptical. “You’re going to have to have a stronger Nexus than that. I can tell you that at this point in time, I’m inclined to to have the state redact,” Nichols said. “If I don’t have a legal reason to keep them in, I’m going to keep them out.” If she were to get a legal argument, she would consider keeping the segments in.

O’Neal invoked the rule of completeness, intended “to qualify, explain or put the original piece of introduced evidence in context,” according to a definition by Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institute.

The judge gave that most weight. Clark argued it’s mixing two entirely different issues. “What she’s talking about is potentially inappropriate behavior of her brother,” Clark said of Avery. “We’re here talking about the sexual acts the defendant committed on her. We have his admissions to the sexual acts in controlled calls. We have his DNA, his semen on her chest, exactly where she said to be found. I just don’t see how it’s relevant.”

The judge asked both sides to get her case law on their arguments. She would issue a ruling later.

Docket sounding, the last step before trial, is scheduled for Dec. 3.

![]()

(*) The name is an AI-generated pseudonym based on girls born in 2013.

Atwp says

How will this end? Will Trump get him out of prison if he go? Trump love to let a certain group men out of prison when there is proof of wrong doing. The capital riots and Sogos, am sure a lot of a certain of men will get out prison under Trumps leadership. We will see what happens.

Just saying says

Between the Epstein files of rich political men raping young girls and the stepfathers raping young stepdaughters when is this child abuse going to end and men be held more accountable?

I feel the charges need to be stricter.

Bo Peep says

To Atwp

Your pal Joey let a lot of people off too even before they were charged with a thing but the. Liberals don’t care for facts do they? But Joey couldn’t pardon himself for showering with his daughter.

Atwp says

Bo Peep, can you prove what you said abut Biden? I can prove about the capital insurrection and Sogos. I have proof do you?

Zoe boy says

Lots of hearsay, looks like he just might beat the case. Free Bun🙌🏾💯