By Ryan P. Mulligan

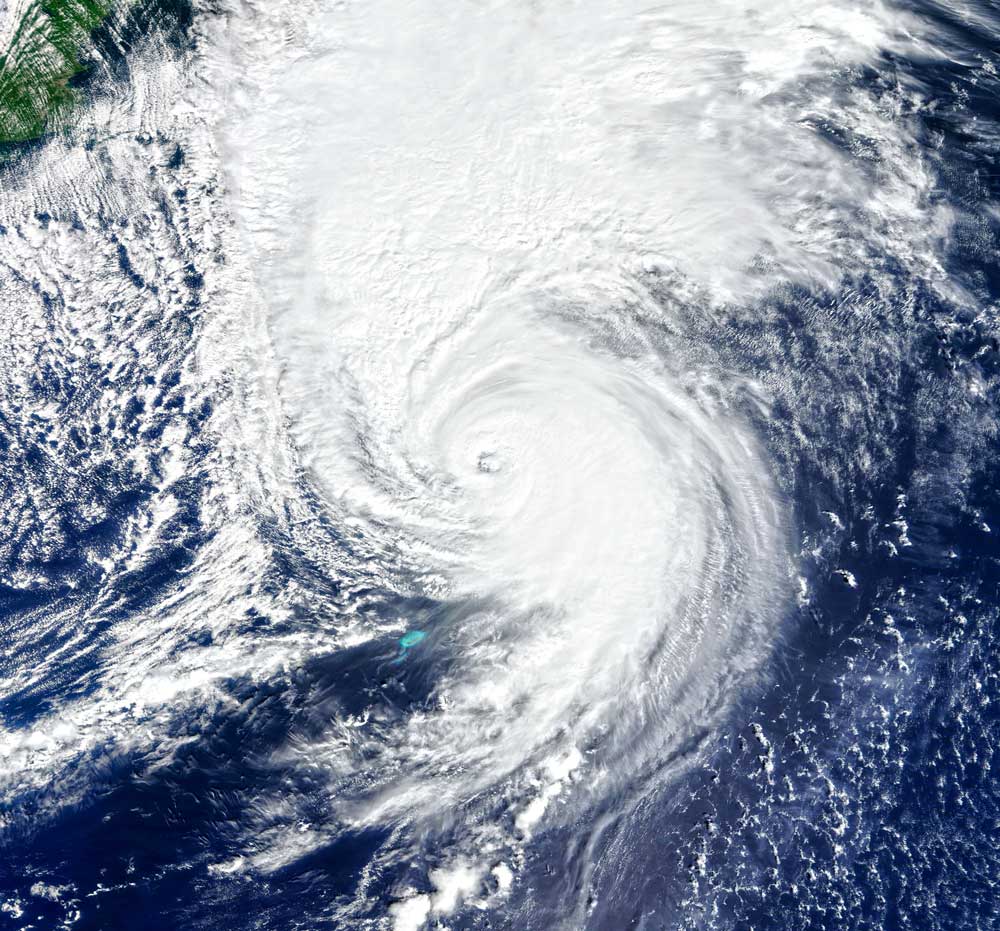

Atlantic Canada has been left reeling from the impacts of one of the largest and most dangerous ocean storms to ever hit the region. Hurricane Fiona made landfall as a powerful post-tropical storm on Saturday along the eastern shore of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador, delivering heavy rainfall, damaging winds and massive waves.

The storm surge — a rise in seawater level — resulted in power outages, flooded roads, and in southwest Newfoundland, homes were washed away. The southwest coast of Newfoundland was hit particularly hard by extreme waves and storm surge, which were highest on the eastern side of the storm track.

The huge storm had a very low atmospheric pressure (931.6 mb) — which is the lowest ever recorded for a tropical storm that made landfall in Canada. Low pressure weather systems are associated with strong winds and heavy rains.

Offshore, the wave heights exceeded eight to 10 metres on the Scotian Shelf and reached 17 metres at the Banqureau Banks wave buoy.

Past storms

Historically, the Saxby Gale of 1869 was a massive storm that caused significant flooding in Nova Scotia. Other more recent storms, such as Hurricane Juan in 2003 and Hurricane Dorian in 2019 had big impacts, but they also weakened in storm intensity just before making landfall in Nova Scotia.

Hurricanes with the size and strength of Fiona do not usually maintain their high wind speeds this far north. This makes Hurricane Fiona a pivotal event in the Canadian coastal ocean, as it raises the question of when this will happen again.

How did Fiona get into Canadian water with such size and intensity? This is related to its heat source: the ocean. Ocean warming may be linked to the increasing intensity of storms making landfall and to the development of strong hurricanes.

So climate change leads to warmer ocean water at higher latitudes. A warmer future increases the probability that more intense storms will reach Canadian coasts.

(THE CANADIAN PRESS/Andrew Vaughan)

Types of impact

Depending on the size and strength of the hurricane, where it makes landfall and the shape of the coast that it strikes, the impacts can be very different.

In addition to large waves and storm surges, hurricanes also bring heavy precipitation that floods the land surface and can affect coastal groundwater systems.

These storms drive strong currents that can erode sediments and change the shape and forms of coasts. They can also affect water quality by suspending and spreading contaminants in harbours.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darren Calabrese

Hurricanes the size of Fiona may not occur again soon — or, a similarly intense storm could strike Atlantic Canada again within the next few years. We are making progress with recent improvements to

hurricane forecasting

and real-time coastal modelling.

Being able to predict the size, frequency and impact of storms helps inform warnings, decisions, responses and policies. These predictions are essential for being ready to face the next big storm event when it happens.

![]()

Ryan P. Mulligan is Professor of Civil Engineering and Director of the Beaty Water Research Centre, Queen’s University, Ontario.

Leave a Reply